hey are two “digital evangelists”. These far-sighted web pioneers of the watchmaking industry have been pushing for digitisation in the industry for the past twenty years.

David Sadigh, founder of the digital agency DLG, and Arnaud Dufour, formerly IT head of e-services at Richemont and professor at the University of Engineering and Management in the canton of Vaud, began their online activities in the watchmaking sector early on – a sector that, despite what we often hear, was an early web adopter, since the first watchmaking brand websites appeared from the mid-1990s.

“They were referred to as brochure sites to start with,” Arnaud Dufour recalls, “an expression that came to have negative connotations. The idea was to present the company and its catalogue. It was no easy task at the time, because the internet was regarded as a highly technical tool, the diametrical opposite of the world of watchmaking with its luxury codes. What’s more, there were genuine technical constraints: with 256 colours and a slow connection, it was difficult to magnify the watches on the screen.”

Incompatibility between luxury watches and the internet

At the time, the aesthetics of luxury were incompatible with a computer screen. This was the golden age of glossy magazines and the web was a poor rival! For a long time, the watchmaking industry stagnated at the stage of simple digital experimentation.

“What the managers feared about the internet was that they saw a lot of illicit players usurping their brand names and diverting their traffic via the search engines,” stresses David Sadigh. “It was really the law of the jungle, and that slowed down the digitisation process.”

The expert sees several reasons why the watchmaking industry did not go digital as rapidly as might have been imagined: “Even when consolidated into groups, the brands knew very little about the end customer. At the time, they felt that the retailers themselves should take charge and develop the approach to the customer.” And the unprecedented growth that the industry was posting in the 2000s was unlikely to make them change their strategy .

-

-

“The first real turning point came with the introduction of the iPhone a decade ago.”

The iPhone, social media and e-commerce threesome

For a long time, growth in the watchmaking industry was cut off from the technological leaps that were so radically changing the times. It continued to function through traditional distribution channels. But gradually, and in disorganised fashion, the industry followed its customers’ changing and increasingly internet-focused behaviour.

Because that was where the money was. The crumbling global economy, falling watch sales in China and the resulting crisis in the industry – a huge build-up of stocks right at a time when the brands had massively invested in their own sales boutiques – also brought about a change of direction towards digital platforms, with pressure coming from shareholders of groups listed on the stock exchange.

“The first real turning point came with the introduction of the iPhone a decade ago,” is David Sadigh’s analysis. “That was when the luxury brands noticed that their wealthy customers were massively adopting that quality interface.” The brands’ top managers themselves were avid converts to the smartphone: “The bosses realised it was easy to publish content on the internet. The impression up to then had been that it was reserved for geeks. It was a major psychological turning point.”

“What’s more, it triggered an organisational crisis among the IT and marketing teams of the watchmaking companies, because the top managers wanted to be able to consult the brand’s emails and website from their iPhones or iPads,”

adds Arnaud Dufour. It was the start of a change of mindset among both the brands and their customers.

The growing social media bubble

Another crucial factor, also helped along by the iPhone and digital mobility, was the emergence and rapid rise of social media to the point where today we are justified, after the initial digital bubble of the new millennium, in talking of a second “internet bubble”: that of social media. Media planning evolved as a result. Until then, the press had been the prime vector for communications in the luxury sector.

But beware of received ideas. According to the WorldWatchReport published by DLG in 2017, the most effective online communications vector today, in terms of traffic generated on watch boutique sites, is neither Facebook nor Instagram nor Snapchat – but the good old newsletter! “Emailing may be less glamorous, but it’s still more effective,” underscores David Sadigh. “The fact that today everybody is addicted to Facebook and Instagram creates false perceptions.”

Transparent prices – no longer taboo?

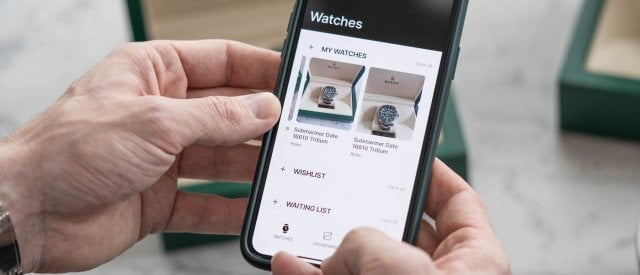

A third turning point concerns e-commerce. “So the idea of communicating online became feasible,” emphasises Arnaud Dufour. “But the idea of selling over the internet, or even displaying prices online, was really taboo for a long time.” Yet there were categories of customer who were prepared to buy luxury watches, or at least conduct part of the purchasing process, online.

“Collectors bought or pre- bought watches over the internet, for example if a model wasn’t available in their geographical region. The psychological barriers were shattered.”

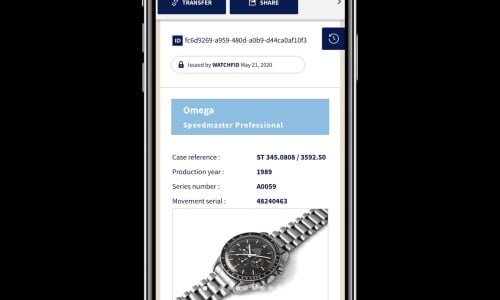

Notwithstanding this, the e-commerce revolution came “from the bottom up”, since – logically – it was the entrylevel brands, most of them non-Swiss-made, that first began selling their products online. But the explosion of the pre-owned market and the emergence of new e-commerce giants, such as Chrono24 (Ed.: see our interview in this folio) were also game-changers.

A mixed bag of initiatives

But let us qualify that remark. Not all the brands have switched to e-commerce, even if numerous announcements to that end have been made – one example is Omega’s investment in its sales platform in the United States last year. “For many players, the internet is first and foremost a communications tool,” Arnaud Dufour believes. “But it is by now accepted that the internet is part and parcel of the run-up to purchasing, even if most of the actual purchases take place in the ‘real world’. The major analysts are all anticipating that by 2025, 20-25 percent of sales transactions will be conducted online.” Obviously, physical boutiques are as important as ever. But consumers get their information online and purchase in boutiques, or vice-versa. Hybridisation is the order of the day, known in marketing-speak as “omnicality”.

Arnaud Dufour: “There are still some big players who haven’t crossed over to e-commerce. Rolex is one emblematic example, even if the fact that it displays recommended sales prices on its site shows that it’s evolving. If those players started selling online, figures would shoot up.”

Retailers left out in the cold

But what hurts is how the distribution networks have been left out of the brands’ digital projects. Since the mid-2000s, the watchmaking groups – especially the Richemont Group brands, but also players like Omega, part of the Swatch Group – have opened a jaw-dropping number of their own boutiques all over the world. A strategy born of their desire for “symmetry” – to control both production upstream (by acquiring suppliers) and distribution downstream (by opening their own sales outlets).

“This rollout also promoted the role of the internet,” David Sadigh believes. “The objective was to channel traffic into these new, expensively rented boutiques, which did not have the advantage of the historical networks of the local retailers.”

Indeed, since being “connected” is a real buzz word today, we should also underscore the brands’ desire to have a direct connection with their end customers. And the resulting bypassing of intermediaries. This development has called into question the brands’ historical partnerships with their retailers, both physical and digital.

-

-

“It would be a good thing if the brands finally assumed their responsibility for their historical distribution network in relation to the internet. Given the way e-commerce has developed for quite a few brands, you can’t deny that the business decisions they took were not to the advantage of the retailers. Yet they’re supposed to be partners.”

An attitude that is more “destructive than constructive”

“As far as retailer digitisation is concerned, we have to differentiate between two types of player,” David Sadigh believes. “First of all, you have retailers with a very local customer base, often going back several generations and with limited means. For them it’s difficult to find the budget or develop online expertise. Then you get the larger retail chains, who have more chance of launching online initiatives with the support of the brands. Both are being confronted with new kinds of customer behaviour, heavily influenced by digitisation.”

Arnaud Dufour points the finger at an attitude on the part of the brands that is more destructive than constructive for their retailers: “It would be a good thing if the brands finally assumed their responsibility for their historical distribution network in relation to the internet. Given the way e-commerce has developed in the case of quite a few brands, you can’t deny that the business decisions they took were not to the advantage of the retailers. Yet they’re supposed to be partners.”

The expert goes on: “If the watch brands really wanted to support their networks, they could! For example, they could suggest to a customer who lives near an authorised dealer to have the product delivered there. That would strengthen the bond with both the customer and the partner. But they don’t do it, as far as I know. Most of the time, the retailers are not integrated into the brands’ digital strategy. Instead, the brands tend to use digitisation so they can have their cake and eat it.”

Integrating digital strategies into discussions with retailers

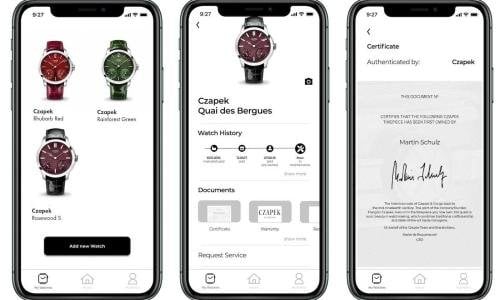

How can we change the game? “I argue in favour of shared ownership of customer data between a brand and the retailers, for example. That would be a real strategic decision that can only come from the CEO. Such a joint customer database would be developed by both partners, for example by sending out joint newsletters. A genuine digital strategy that includes the retailers would reassure them.”

Because numerous prospects are opening up: “Customer data management software is really in its infancy,” is Arnaud Dufour’s analysis. “The same goes for online after-sales service.

The idea of virtual communities or clubs turned out to be a damp squib. Everything needs to be done from scratch. So why not include the retailers in these processes?”

Like a headless chicken...

But should the brands invest first in renovating their websites? Or promoting their social media? Or launching an online boutique? The sheer number of options makes your head spin! Ultimately, you get the impression that the brands are exploring any number of paths, at a loss what to do faced with so many online tools. There are so many possibilities that too many brands seem to be shooting in all directions at once, investing a little (or a lot) in everything, rather than concentrating on one, clear-cut, digital strategy. A bit like a headless chicken that goes zigzagging in all directions.

And they are not all shooting together: “All the brands are stepping up their digitisation, but not all at the same pace,” underscores David Sadigh. “It often happens that the large budgets allocated specifically to digitisation are not used optimally. The problems most frequently encountered are related to the purchase of key words that cannibalise organic traffic, advertising banners that generate low-quality traffic, or too much energy poured into the social media.”

Click here to get back to

“12 DISRUPTIONS IN THE WATCHMAKING INDUSTRY”