A history of watch advertising

By Marco Strazzi

1900-2000: A history of watch advertising

esearchers studying 20th century watchmaking have an invaluable resource at their disposal: the archives of specialist periodicals. They make it possible to observe history as it happened, almost like time travelling. Take Europa Star, for instance. Across the decades, the magazine’s various international editions have featured articles on manufacturers, news, technology, trade fairs and sales techniques – not to mention thousands of advertising pages. These ads capture the spirit of the times in a way that mere commentary cannot.

The images, graphics, writing styles and even the choice of typefaces uniquely and unmistakably express how the manufacturer perceived its product, and how it wanted the public to perceive it once available in stores. It’s like witnessing history in real time. Moreover, these ads from the past also illustrate how design and public tastes have evolved, providing reference points for enthusiasts looking to accurately date vintage watches.

In short, there are many compelling reasons to explore the images and slogans that showcased manufacturers’ creativity, beyond the purely industrial and technical realms. To make it easier to follow, we’ll explore this history chronologically, across nine distinct periods.

About the author Marco Strazzi is the author of a two-volume work on 20th century watch advertising. Published by Pressision SA, Watch Ads 1900-1959 and Watch Ads 1960-2000 are bilingual English-Italian and can be purchased online. PDF previews can be consulted online at 10e10.ch.

A history of watch advertising: 1900-1919

he turn of the 20th century marked the emergence of the wristwatch as a commercial product. While women embraced the new accessory, men and industry insiders were sceptical.

Why wear a watch on your arm, exposing it to shocks and the vagaries of the weather, when you can rely on a tried and tested, well-protected pocket watch? Consequently, the pocket watch maintained its market dominance, shaping the marketing strategies of manufacturers who continued to prioritise it.

-

- 1905: In this 1905 Longines ad, the pocket watch is the undisputed star. Its popularity remains unchallenged (for now).

It wasn’t until the 1910s that the focus began to shift, primarily as a result of the outbreak of World War I. The coordination of wartime operations required practical, durable and water-resistant timepieces. To meet these novel demands, manufacturers developed and patented innovative solutions. Newspaper advertisements showcased features such as waterproof cases, fixed or removable metal grids to protect the glass, and luminescent indices and hands for reading the time in the dark. These ads captured the pressing needs and concerns of the era.

-

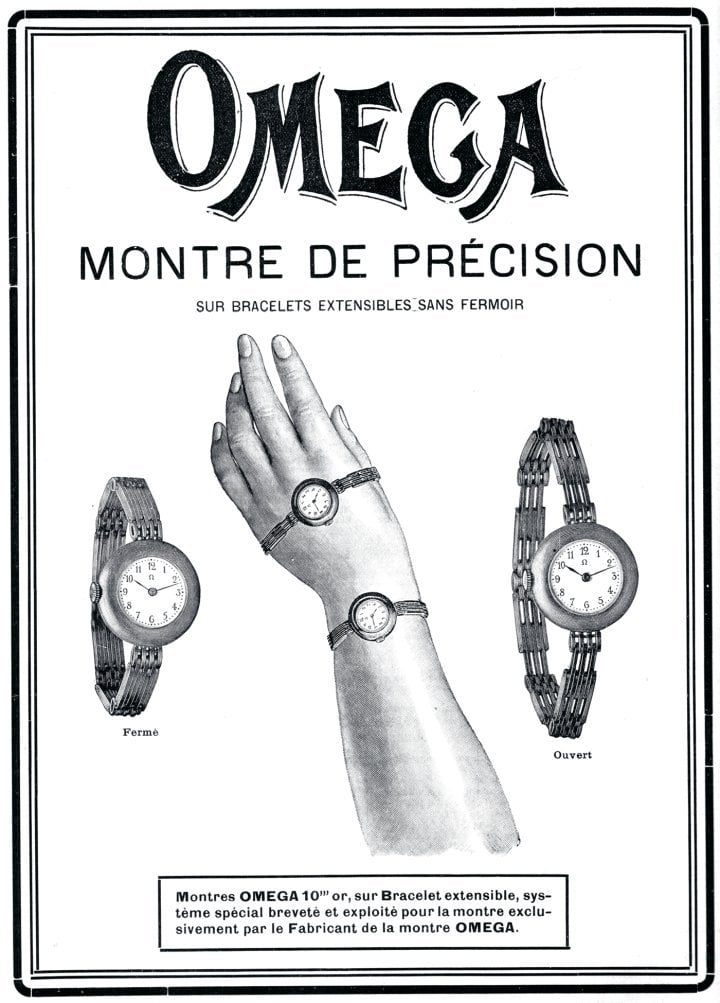

- 1908: In the first decade of the 20th century, wristwatches were primarily a feminine accessory, as demonstrated by this Omega timepiece featuring an innovative extendible bracelet.

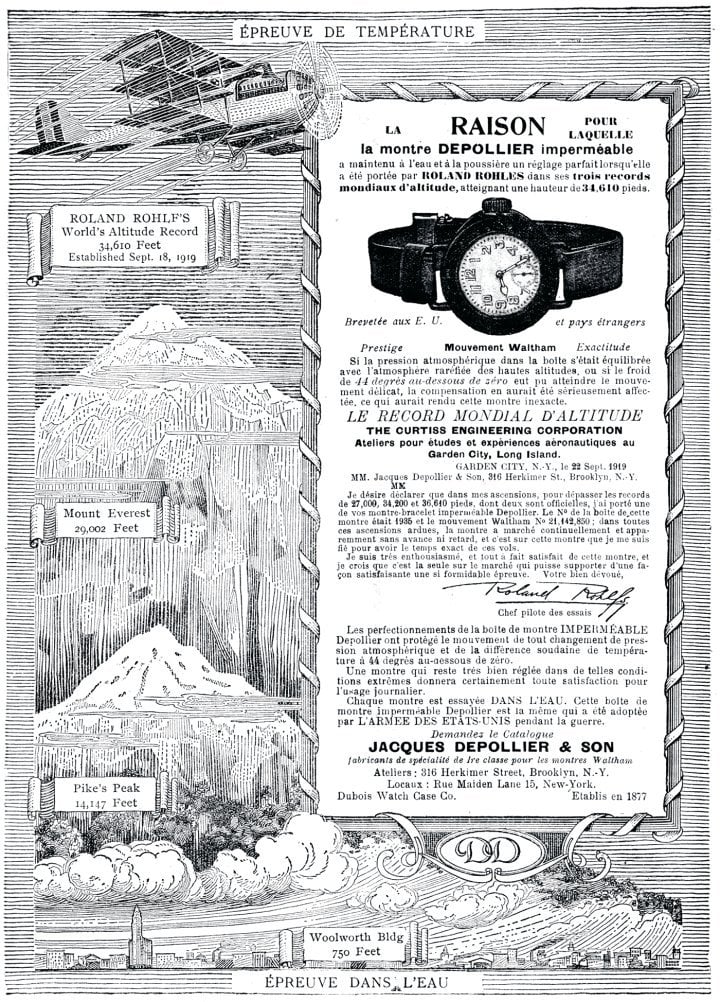

The Swiss industry dominated the international market, supplying timepieces to numerous armies worldwide. However, the United States also produced models designed to withstand harsh environments. In 1919, the trade press published the first advertisement linking a wristwatch to a celebrated figure and achievement: aviator Roland Rohlfs and his altitude record.

-

- 1910: Patented in Germany, this elastic clasp can be attached to a strap or metal bracelet, making it possible to convert a small pocket watch into a wristwatch – the ideal accessory for style-conscious women (Béguelin-Piaget).

-

- 1914: An early Swiss specialist in water-resistant cases was François Borgel. Two pocket models and one wristwatch are showcased in this ad. The wristwatch gained the trust of soldiers on the front lines of the Great War.

-

- 1916: Wartime demands inspire another innovation: a removable metal grid to minimise the risk of glass breakage (Idéal).

-

- 1919: From the trenches to aviation records: the waterproof Depollier model, adopted by the American military during the war’s final months, accompanied pilot Roland Rohlfs on his 10,000-metre altitude ascent. This advertisement devotes extensive text to its features – an unusual approach in an age dominated by image-rich ads.

A history of watch advertising: 1920-1929

he rise of the wristwatch was unstoppable, punctuated by events that bolstered its image and cemented its success. The Swiss Fair in Geneva (1920), the Paris Exhibition (1925 – famously known as the birthplace of the Art Deco style), and the Universal Exhibition in Barcelona (1929) celebrated the fusion of technology and jewellery, consolidating the appreciation of the female audience.

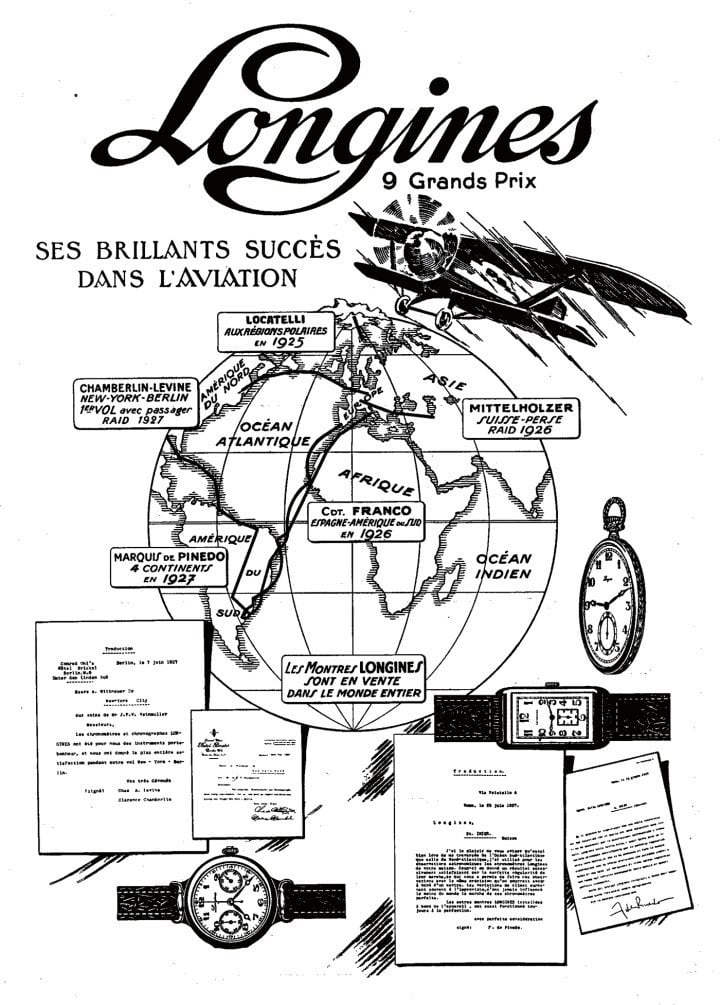

Athletes, explorers, aviators, and show business stars wore their timepieces as they engaged in a variety of activities, all of which garnered media attention. Watch brands recognised that associating their products with contemporary heroes offered a significant advantage in capturing the male market, and advertising played a crucial role. Longines associated itself with aviation records, Rolex launched the Oyster by pairing it with swimmer Mercedes Gleitze, and several manufacturers capitalised on the success of sports competitions to promote their chronographs.

-

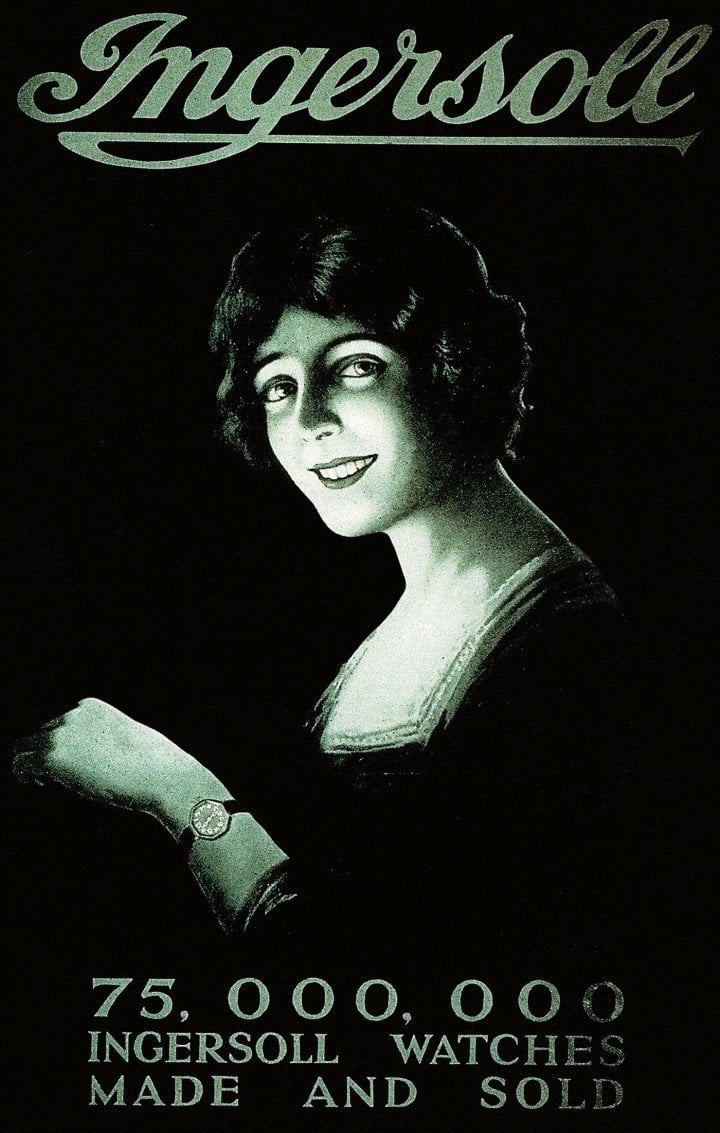

- 1922: This advertisement, published to celebrate 75 million watches sold by Ingersoll, reflects how the brand, like much of American industry in the early 1920s, still tended to identify wristwatches with a female audience.

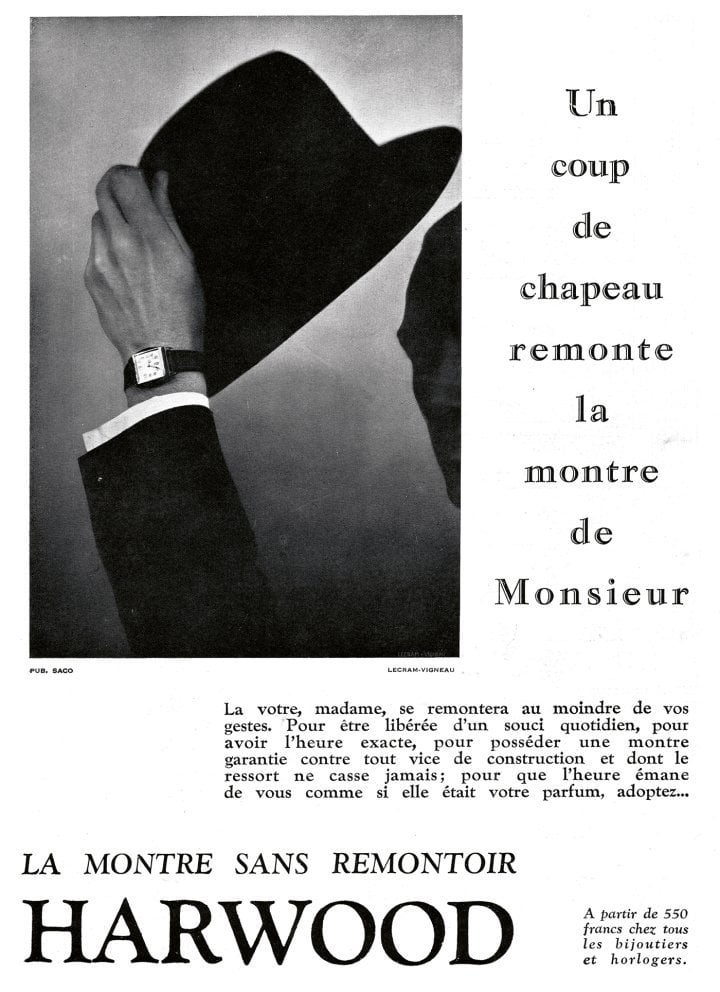

At the same time, watch technology broke new ground, and advertising campaigns highlighted these innovations. LeCoultre, Harwood and Glycine introduced the first two-level movement, the first automatic wristwatch and the first with the Geneva Seal, respectively. Most advertisements showcased rectangular and square-shaped cases, which, in the eyes of customers, had the merit of emphasising the distinction with the typically round pocket watch. The latter’s presence in advertisements diminished significantly, as it became clear to everyone that the future belonged to the wristwatch.

-

- 1925: Pictured here are some of the jewellery watches presented by Ebel at the 1925 Paris Exhibition, a style and an event emblematic of the Roaring Twenties.

-

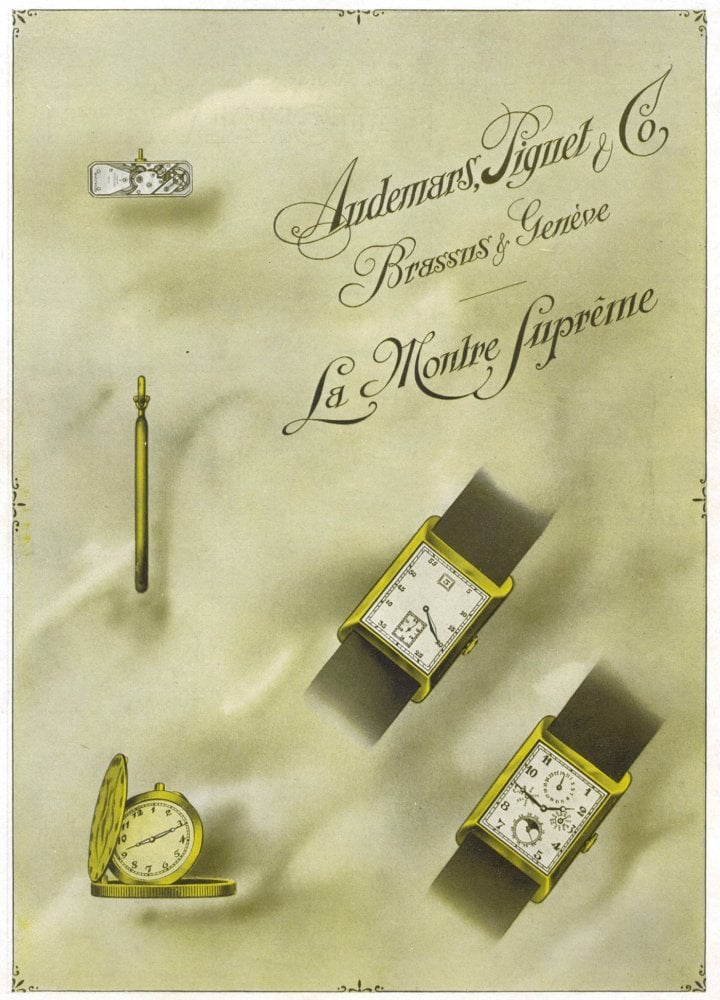

- 1925: Audemars Piguet, a specialist in complicated watches from the outset, miniaturised their movements to fit the cases of wristwatch models, with a focus on rectangular shapes, as its audience’s taste dictated.

-

- 1927: Longines, the official partner of the International Federation, built a strong association with aviation. This ad highlights the records set by pilots who relied on its timepieces.

-

- 1928: This presentation introducing the Rolex Oyster – the watch that “defies the elements” – emphasises a recurring theme in Rolex communication: precision certified and recognised by official control agencies.

-

- 1929: “Wind your watch by tipping your hat”: the greatest innovation of the end of the decade was the automatic wristwatch, patented by British inventor John Harwood and manufactured in Switzerland.

-

- 1929: Featuring a movement that met the stringent standards of the Geneva Seal, Glycine offered “the precision of a pocket chronometer in a wristwatch”. This wording implies that wristwatches were on the cusp of surpassing pocket watches in the eyes of the public.

A history of watch advertising: 1930-1939

he watchmaking industry reacted to the Great Depression of the early 1930s with remarkable inventiveness, revolutionising almost every technical and aesthetic standard. The introduction of steel led to the decline of silver, which, until the previous decade, had been the only alternative to gold in high-quality products.

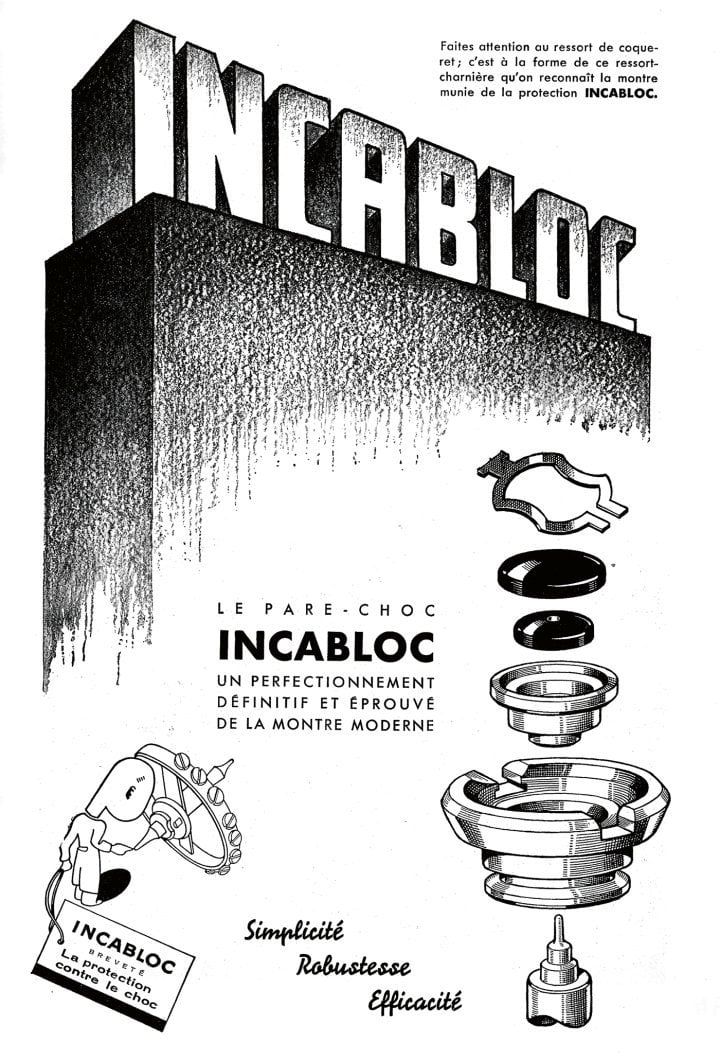

The first effective shock-proof device (Incabloc) and models with “armoured” cases dispelled the remaining clichés about the fragility of wristwatches. Rolex combined the Perpetual automatic movement with its waterproof Oyster case; Mimo introduced a model with a digital date display; and Breitling launched the two-pusher chronograph.

-

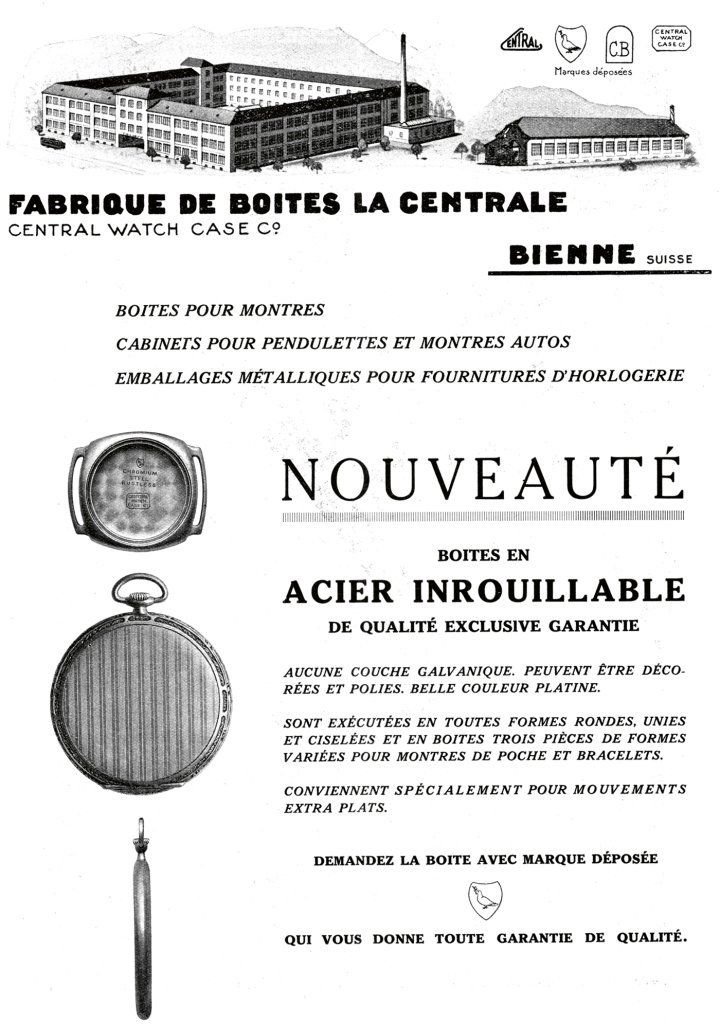

- 1930: Biel-based case manufacturer La Centrale announces the adoption of a new material in watchmaking: stainless steel. The image of the large-scale factory, a common feature in advertisements since the 1910s, demonstrates the advertiser’s considerable production capacity.

Designers opted for austere and functional elegance, creating models that would become icons: the Reverso (LeCoultre) and the Calatrava (Patek Philippe). Initially, these innovations didn’t achieve the desired success: times were challenging and sales stagnated.

-

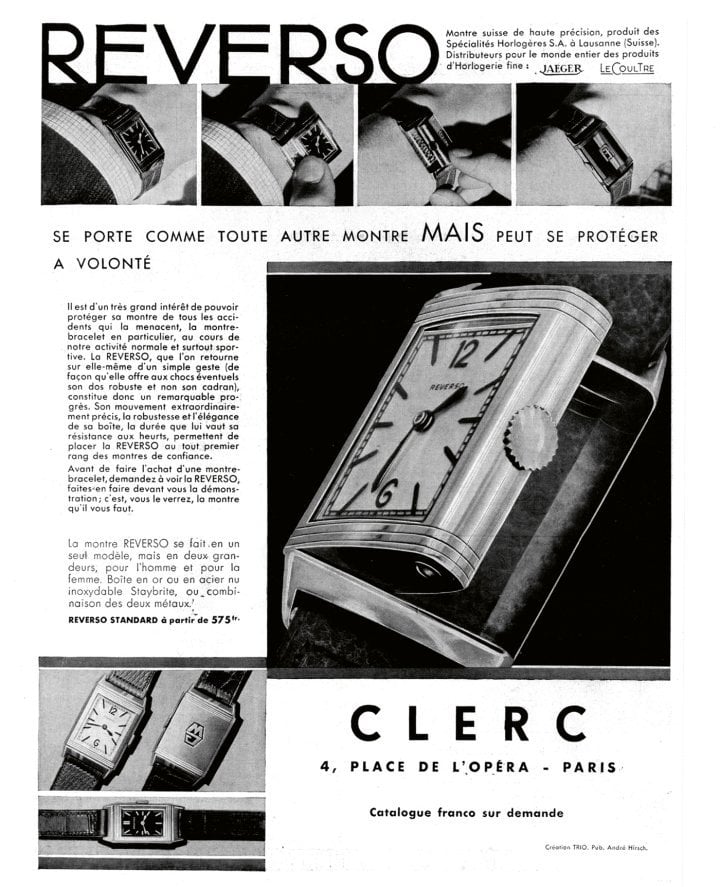

- 1931: This photo sequence showcases the workings of the LeCoultre Reverso, which can be “worn like any other watch but protected at will”. Published by a Parisian retailer, the advertisement gives considerable space to the text, reflecting a fairly widespread trend during that period.

As often occurs during a crisis, investment in advertising declined. Lacking the necessary ads to secure their funding, magazines became noticeably thinner. The number of pages started to increase around 1934, signalling the beginning of the recovery. Along with the latest creations – Driva’s inexpensive wristwatch repeater, Bovet’s simplified rattrapante, Marvin’s motorist’s watch, among others – came increasingly sophisticated advertisements, extending the competition between manufacturers to communication and image.

-

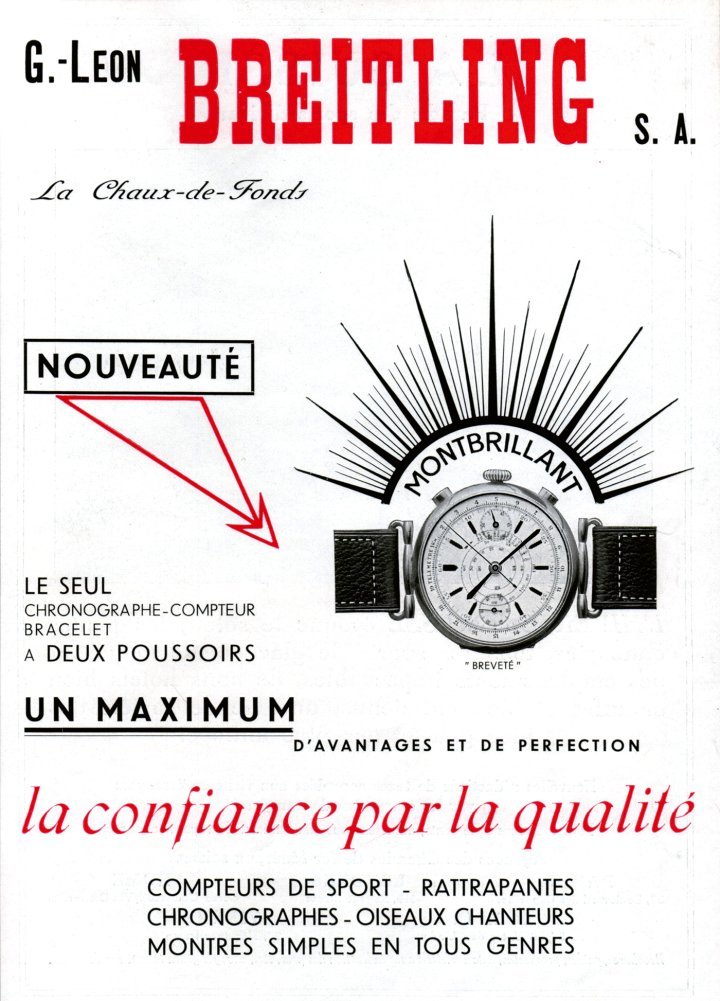

- 1933: Breitling introduces “the only wrist chronograph with two pushers” with a presentation enhanced by varied typography and attractive graphics.

-

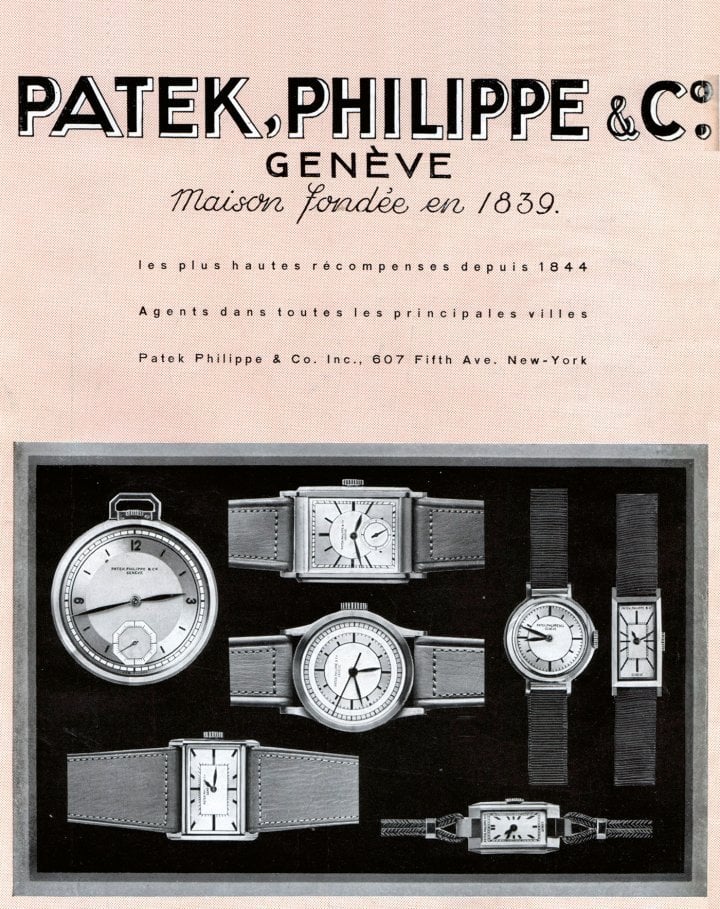

- 1934: The brand new Reference 96, later christened the “Calatrava”, takes centre stage in the photograph. Patek Philippe’s communication strategy diverges from other brands, consistently prioritising visuals over text.

-

- 1937: To promote its “sensational” hour and quarter repeater, Driva’s designer superimposes the watch’s image onto those of two potential buyers, suggesting that the model is unisex.

-

- 1938: The locomotive and the Oyster Perpetual are hailed as “two masterpieces of modern technology”. Typical of Rolex advertisements from the first half of the century, the text adopts an almost didactic tone, explaining that the automatic movement offers exceptional regularity and that the Oyster case is water-resistant to 6 atm.

-

- 1939: The Incabloc anti-shock device, patented in 1933, significantly enhanced wristwatch reliability. The advertiser’s choice to make a wall the central element is an effective if unsubtle allusion to robustness.

A history of watch advertising: 1940-1949

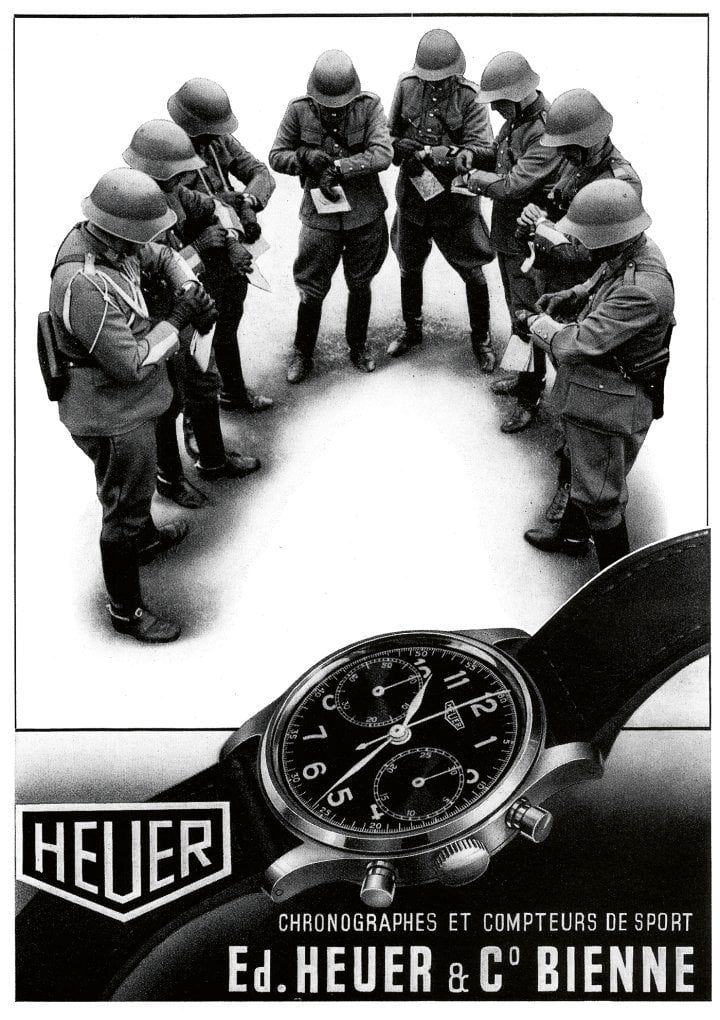

he first half of the decade was impacted by the war. The demand for precision instruments from all countries in conflict provided a significant boost to the Swiss watchmaking industry, which, despite supply challenges, accounted for one-third of national exports and 86% of the global market. Manufacturing focused on products suitable for military use, and advertising reflected this, while emphasising that robustness and reliability were equally important in civilian life.

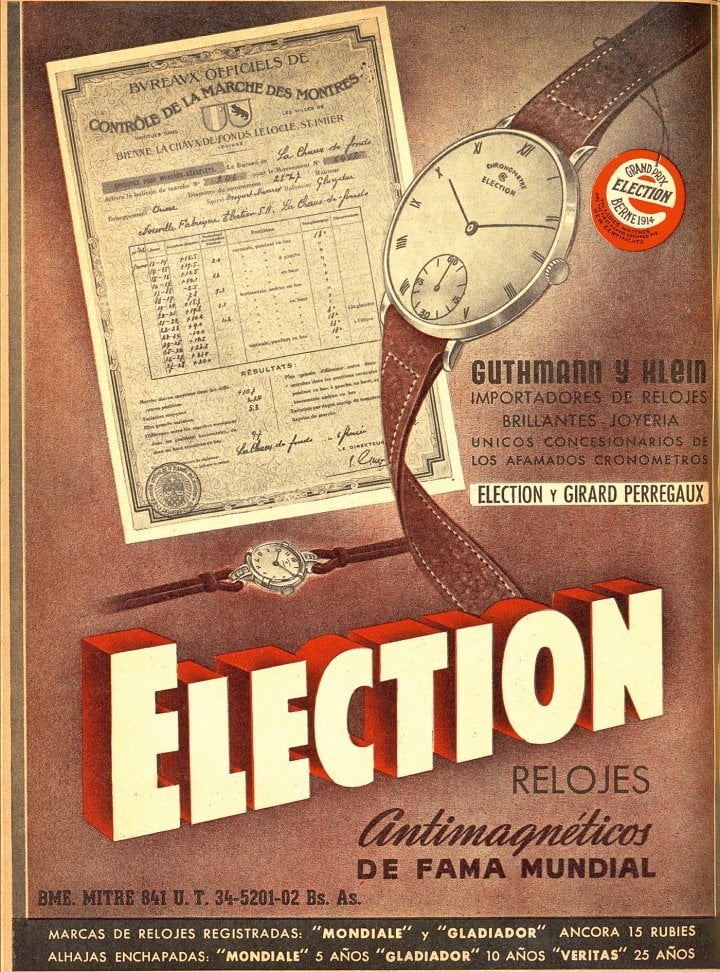

A growing awareness of the importance of effective communication emerged within the industry. In 1942, the newly-founded Revista Relojera in Argentina dedicated entire pages to the technical presentation of Swiss watches.

-

- 1941: Advertising cannot ignore current affairs. In Switzerland, a German invasion is feared and the army prepares the country’s defence. The image of officers synchronising their watches, chosen by Heuer in combination with a waterproof chronograph, speaks volumes.

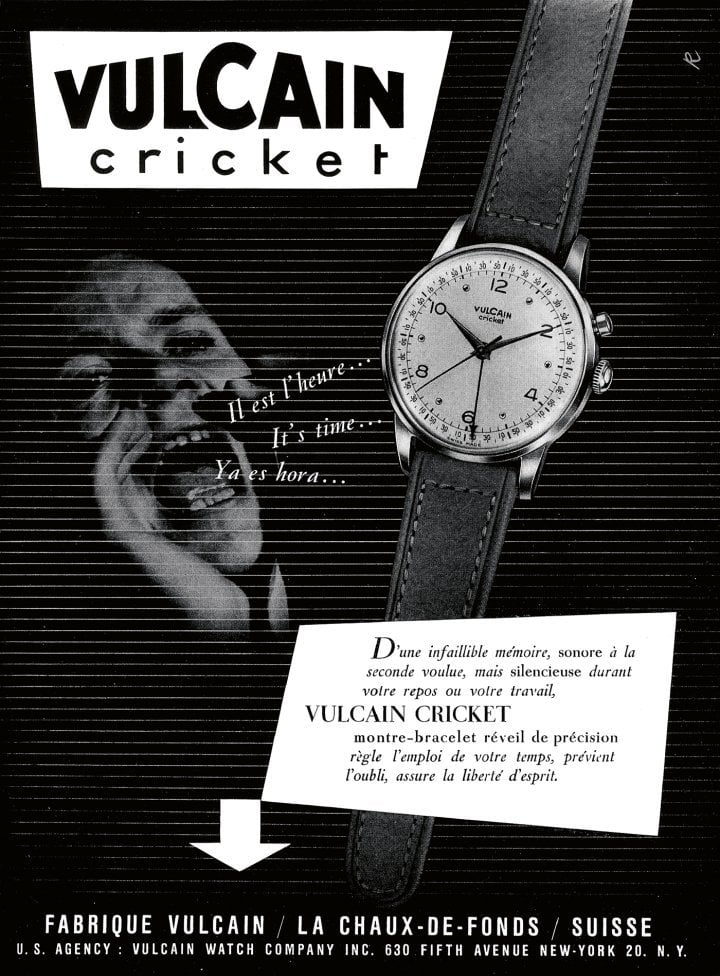

From 1945 onwards, creativity and cutting-edge technology regained prominence in both industry and marketing. The first ultra-thin wristwatch (Audemars Piguet) and the first with an effective alarm (Vulcain) were introduced. Automatic watches became more appealing thanks to the digital date display (Rolex), the complete calendar (Movado), the power reserve indicator (Jaeger-LeCoultre, Zodiac), and winding by ball bearings (Eterna).

-

- 1942: The certificate of chronometric accuracy issued by official control agencies features in some advertisements, highlighting a sales argument to which manufacturers attach increasing importance (Election).

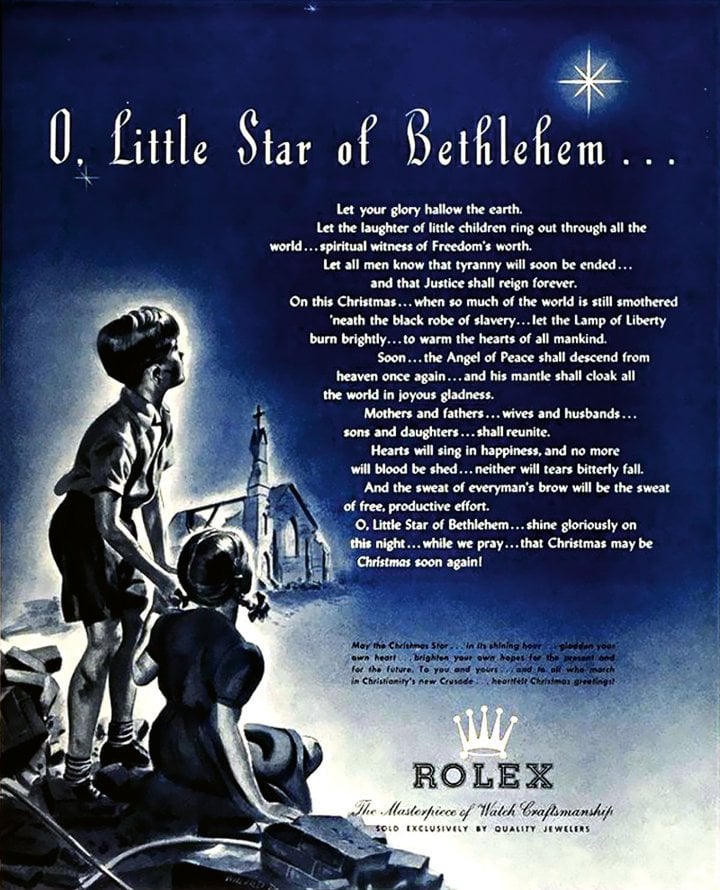

For women with above-average purchasing power, jewellery watches featuring small precious metal cases and stone-set bracelets were available. This new golden age extended to the advertising sphere, as companies invested a portion of their substantial profits in campaigns enriched by illustrations, some of which were masterpieces of graphic art.

-

- 1942: Omega’s communication caters to the demand for watches with enhanced waterproofing, showcasing its ‘hermetic’ models and a diver walking among fish. Published in neutral Argentina, the ad avoids any reference to potential military use.

-

- 1943: Another ad inspired by contemporary events. Rather than showcasing its products, Rolex chooses the title of a Christmas song and a text that acknowledges the suffering caused by the war while expressing hope for a better future.

-

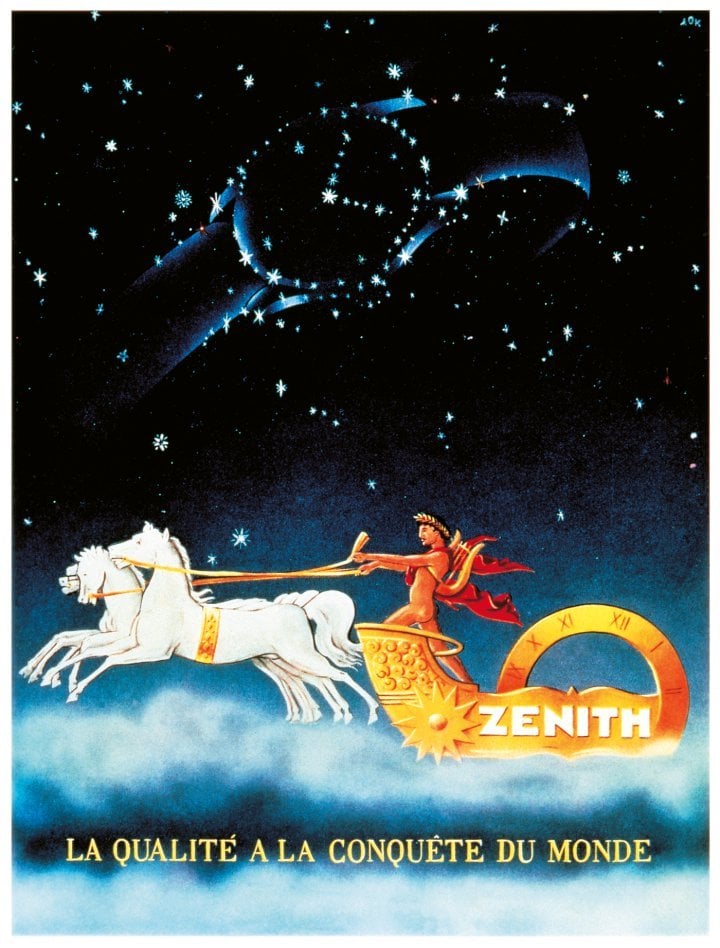

- 1948: A constellation formed by a clock illuminates Apollo and the chariot of the Sun traversing the celestial vault. This is an example of the sophisticated illustrations that characterise some of the most striking post-war advertisements (Zenith).

-

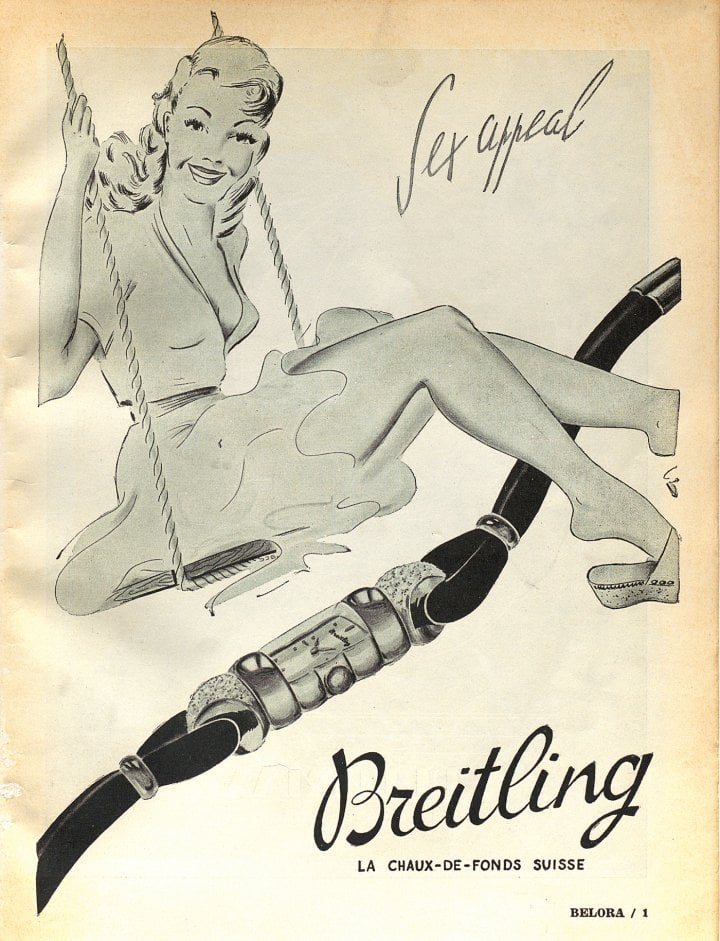

- 1948: The ‘sex appeal’ of jewellery watches: the image is designed to capture the attention not only of women, but also of men who might purchase the item for their wives or girlfriends (Breitling).

-

- 1949: “The Cricket precision alarm watch manages your time, prevents forgetfulness, and frees your mind” – Vulcain loudly proclaims its innovative new feature.

A history of watch advertising: 1950-1959

he “tool watch” graced the wrists of explorers, mountaineers, pilots and divers as they shattered records of all kinds.

Feats such as expeditions to Mount Everest and descents into the depths in the bathyscaphe Trieste captivated the public’s attention and imagination. Manufacturers recognised the commercial potential of these events and advertised tool watches tailored to those who aspired to emulate the heroes of the moment or, more modestly, just wanted a watch that suited an active lifestyle.

-

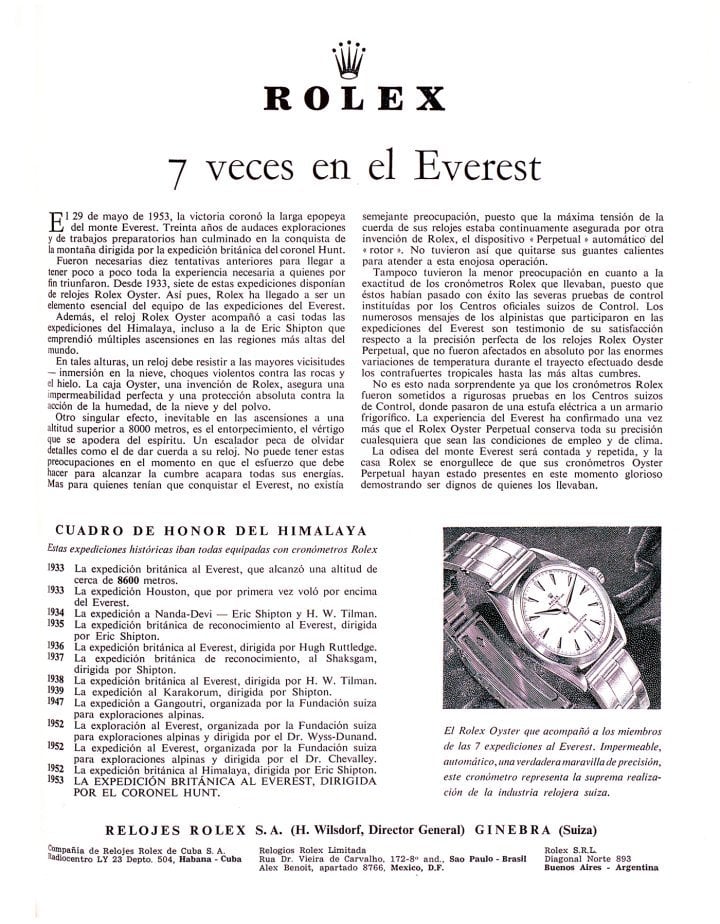

- 1953: “7 times on Everest”: This Rolex ad, with its limited use of imagery, highlights the fact that the company’s watches had been part of expeditions to the world’s highest peak for 20 years — a style characteristic of Rolex’s communication during this time.

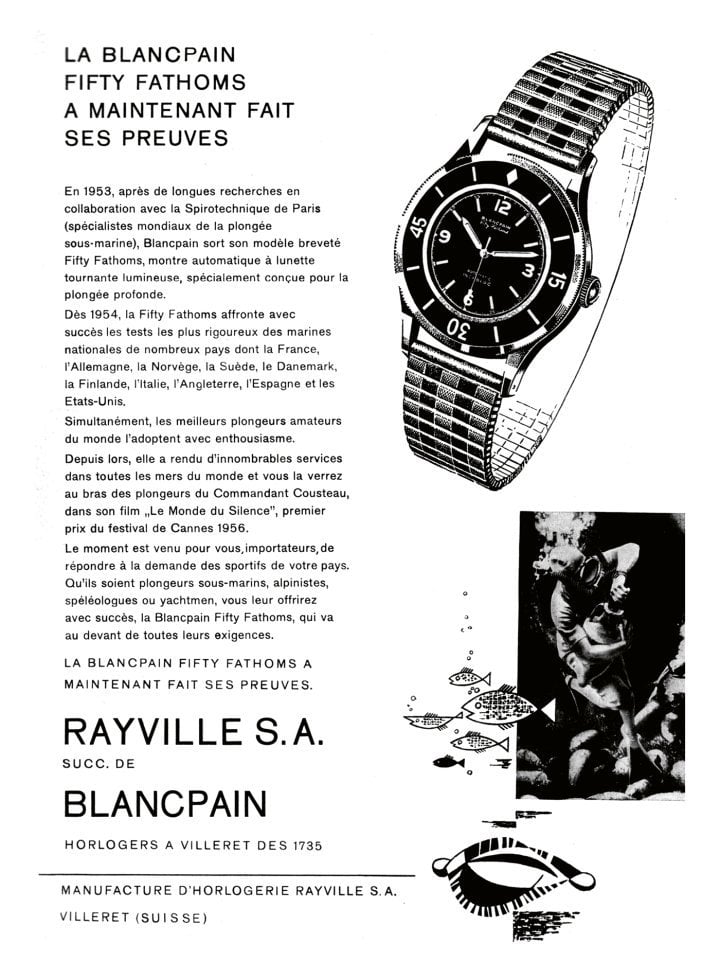

The burgeoning popularity of scuba diving spurred the production of timepieces resistant to water pressure (Rolex, Blancpain). Pilots and air travellers could rely on models boasting dual time zones, world time, and calculation functions (Breitling, Movado, Tissot). There were watches for fishermen (Heuer), hikers (Sandoz) and professionals working near magnetic fields (IWC).

-

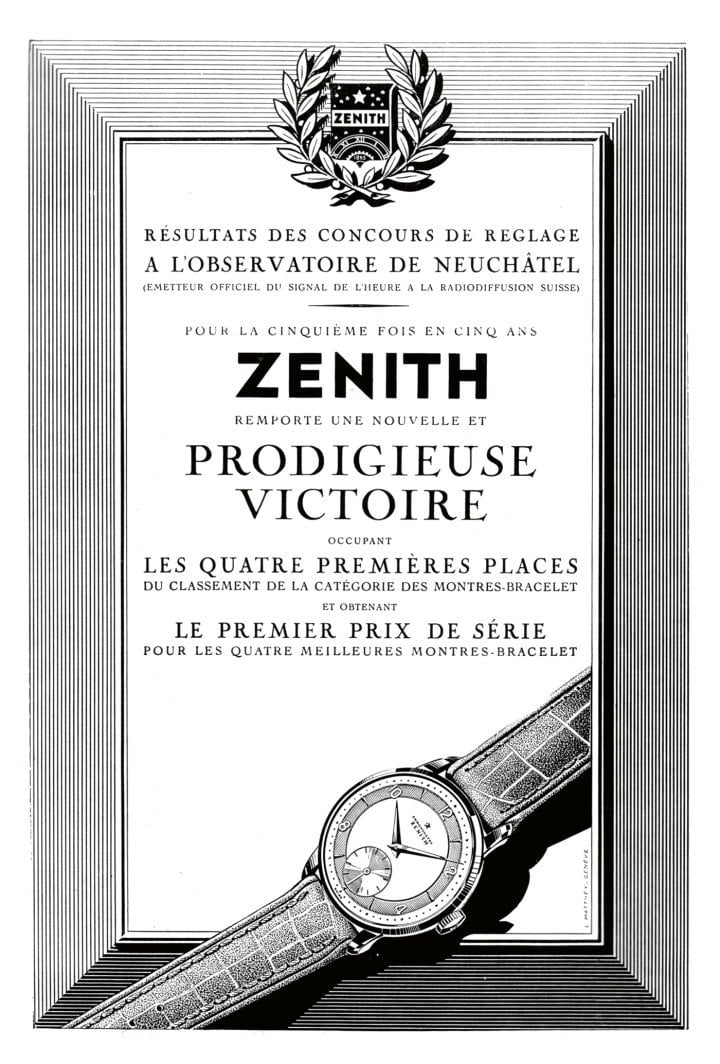

- 1954: Success at the Geneva and Neuchâtel Observatories’ precision competitions became an important promotional tool. Here, Zenith celebrates a “new and prodigious victory” in Neuchâtel, marking their fifth win in a row.

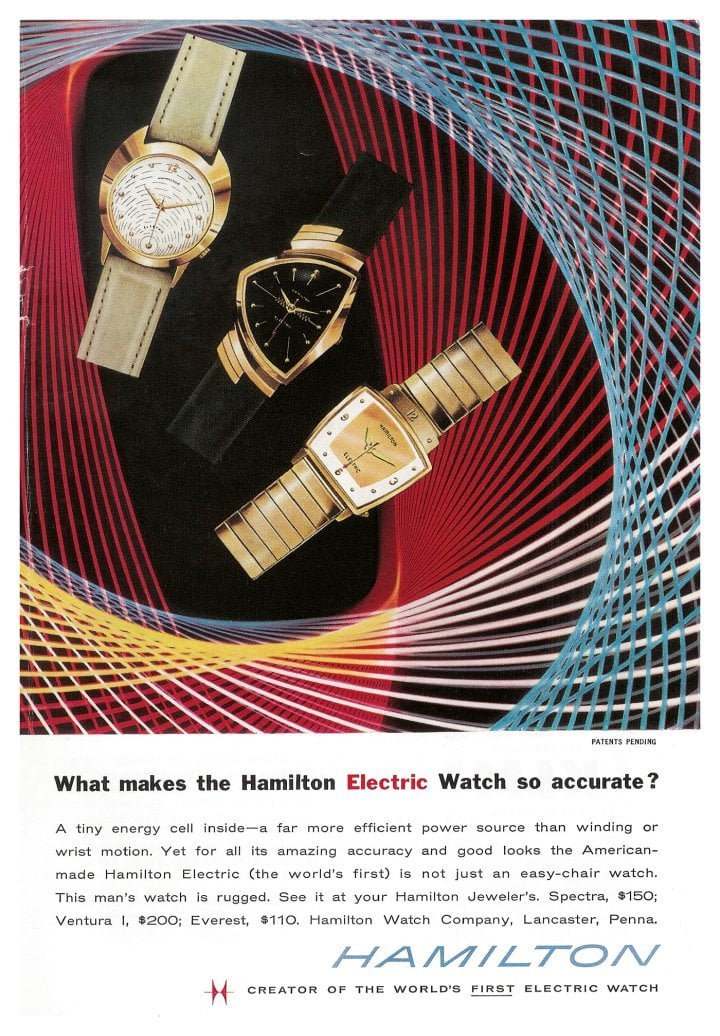

The majority of these innovations hailed from Switzerland, and relied on automatic movements that boasted superior reliability and more compact dimensions than before. Notable examples included competitions for the world’s thinnest and smallest calibre. Meanwhile, the American (Hamilton) and French (Lip) industries unveiled electric wristwatches, fusing technological progress with distinctive aesthetics. This diverse production landscape necessitated a shift in advertising, which had to engage with increasingly discerning and varied audience segments.

-

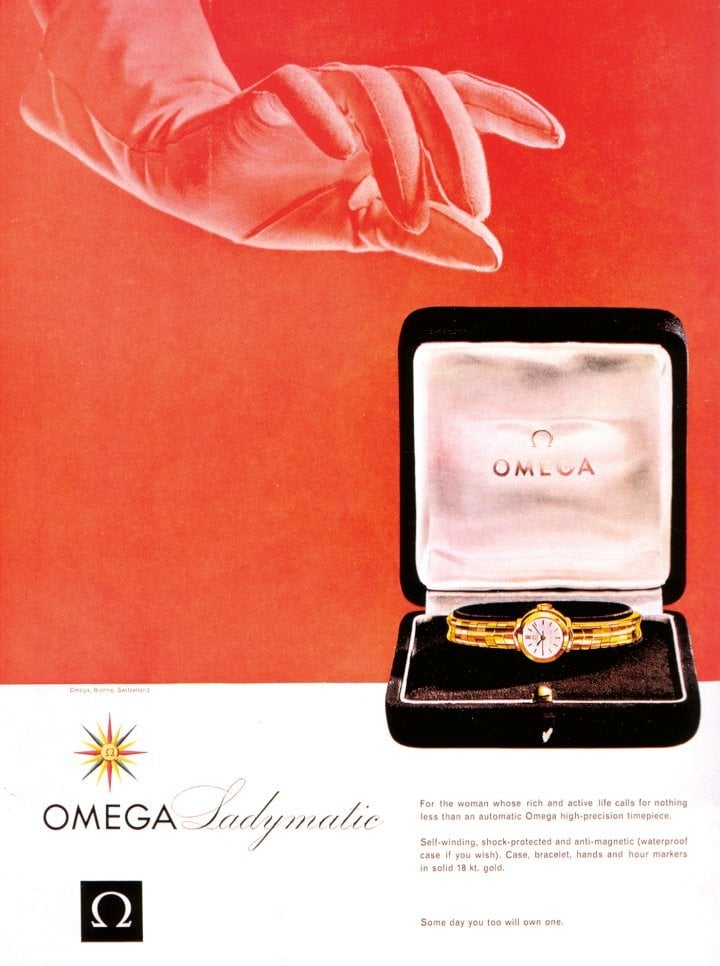

- 1955: A gloved female hand reaches out towards the Ladymatic, suggesting that Omega’s compact design and automatic movement perfectly meet the needs of the elegant, modern and active woman.

-

- 1957: Blancpain’s Fifty Fathoms, one of the first mass-produced dive watches, is showcased in an ad that traces its journey from initial tests in 1953 to its adoption by various navies in 1957, and its appearance in the 1956 documentary “The World of Silence”.

-

- 1958: The first electric wristwatch not only ensures “amazing accuracy” and “good looks”, it’s also robust. This Hamilton ad features the Spectra, Ventura and Everest models, from left to right.

-

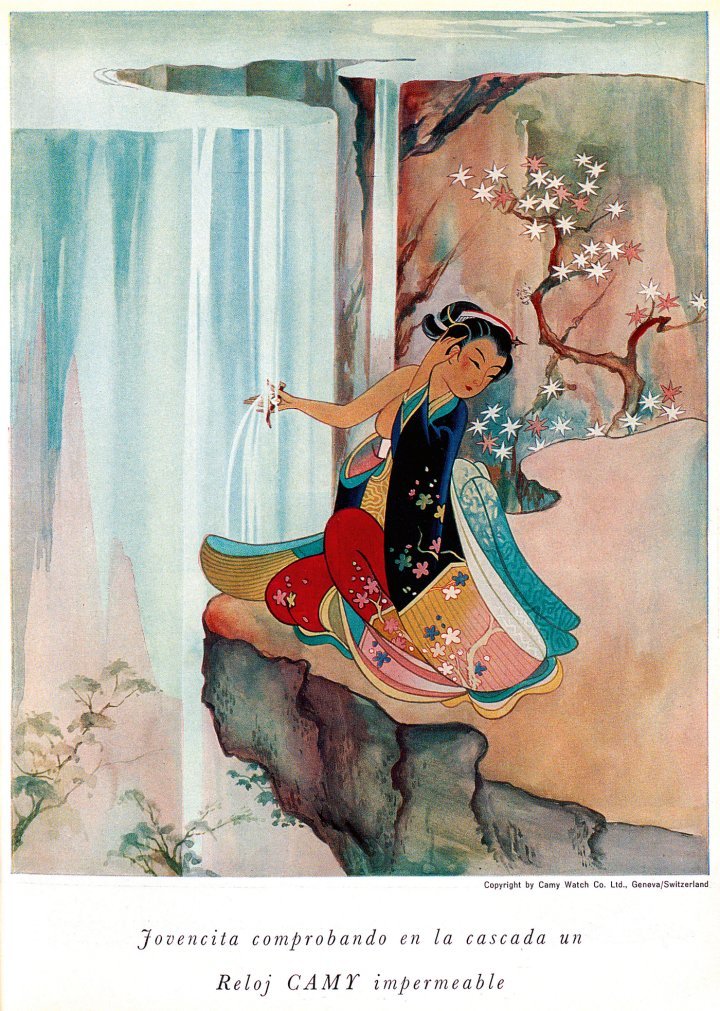

- 1959: Inspired by oriental art, this illustration shows a girl testing the Camy waterproof watch under a waterfall, offering a refreshingly original approach to a subject typically discussed in terms of technical features and practicality.

-

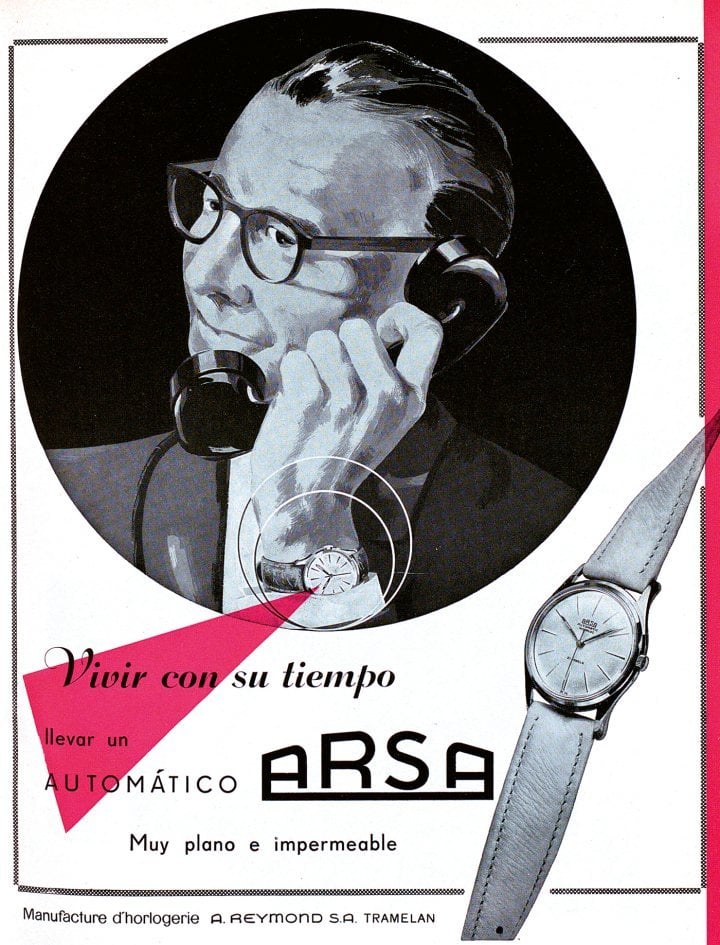

- 1959: “Living in today’s world” means wearing an ultra-flat, waterproof Arsa automatic. Many manufacturers felt the need to inform the public about the practicality of automatic watches, which were still struggling to gain widespread acceptance, and the progress that had been made.

A history of watch advertising: 1960-1969

he watch of the space age”: that was how Bulova introduced the Accutron, which used a tuning fork instead of a balance wheel as its regulating organ, kicking off the electronics revolution.

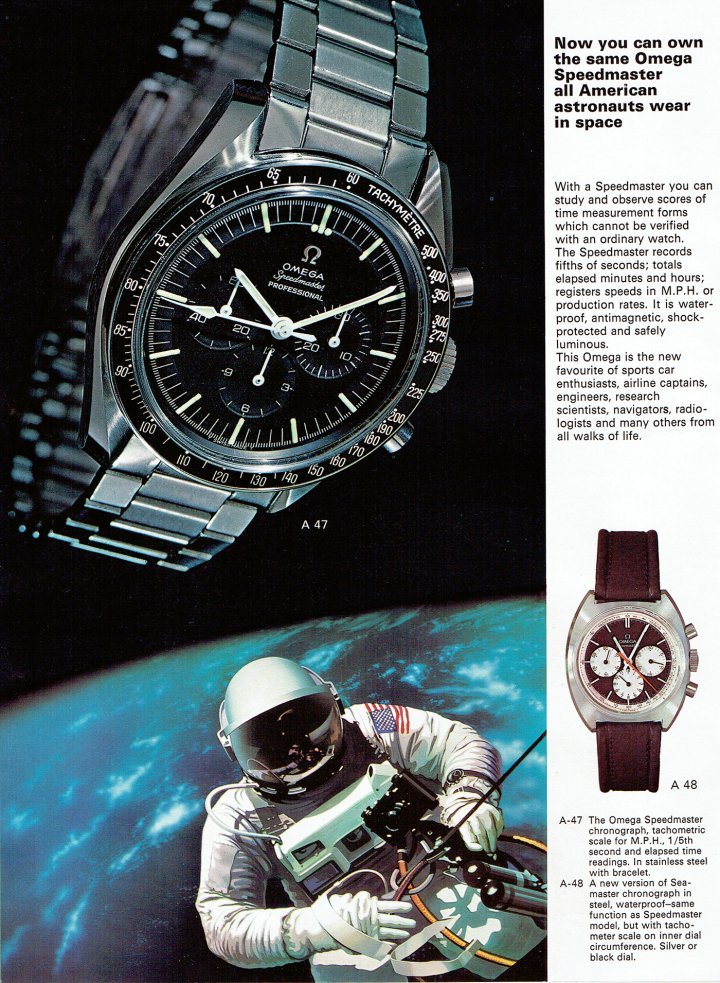

While its role in NASA missions was limited to being an on-board timer, the more traditional Omega Speedmaster – a mechanical chronograph – handled the harsh conditions of outer space. The Speedmaster became a bestseller, partly thanks to ads that highlighted its connection to the astronauts’ adventures.

-

- 1961: “First electronic watch with tuning fork”. This Bulova advertisement highlights the components of the Accutron movement, offering an unprecedented glimpse to the public of that time and appealing to buyers who wanted to feel ahead of the curve.

Switzerland and the United States, locked in an increasingly fierce technological and industrial arms race, were slow to see the new threat on the horizon. By mid-decade, Japanese products had landed in Europe, and soon became major players in terms of innovation. Seiko was among the first companies to unveil an automatic chronograph, shortly after Zenith, Breitling, Heuer and Hamilton, and was the first to market a timepiece that would change the face of the watch industry: the quartz wristwatch.

-

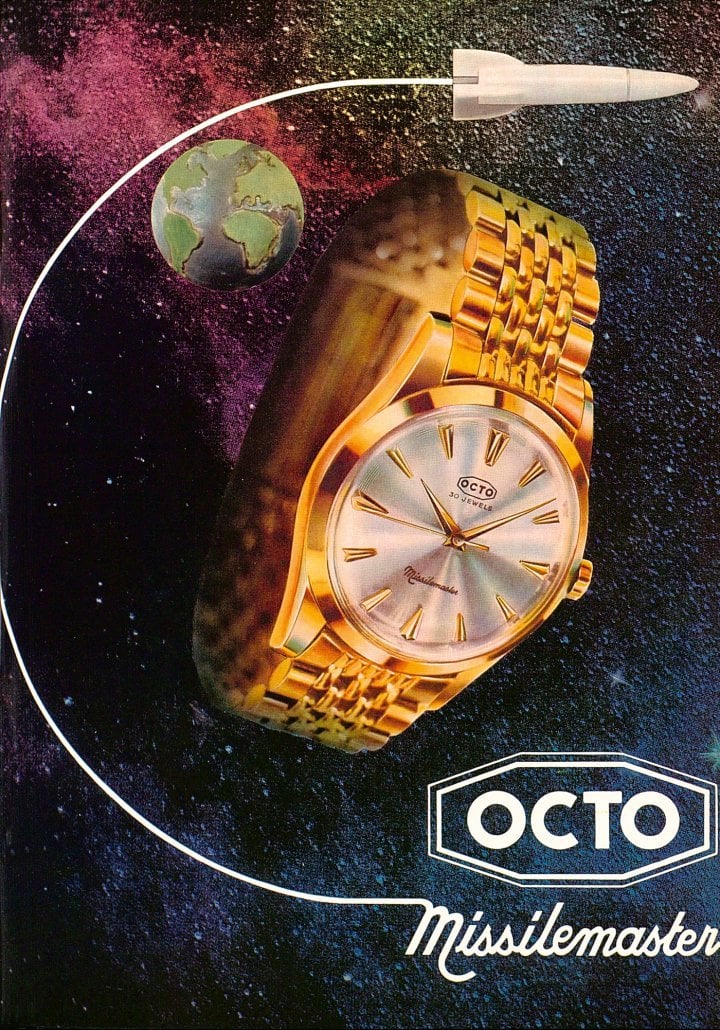

- 1961: The Octo Missilemaster sports a fairly conventional appearance, but its model name and advertising image tap into the allure of space exploration to emphasise its modernity.

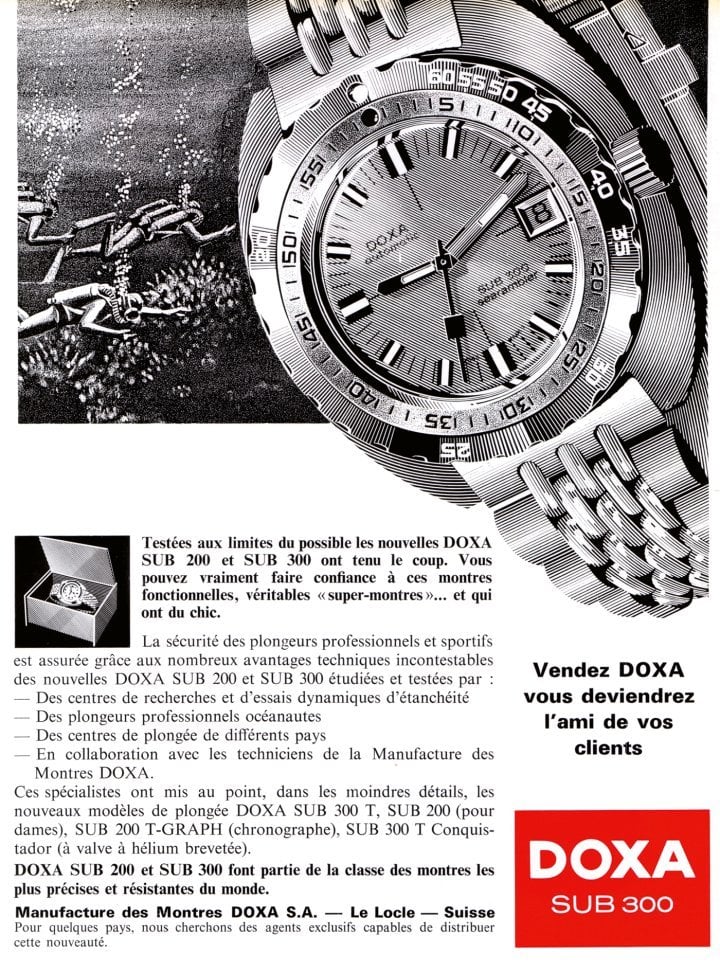

Meanwhile, cutting-edge materials like tungsten carbide (Rado) and glass fibre (Tissot) made their debut, as did increasingly robust waterproof diving models (Doxa, Rolex). One even had an alarm (Vulcain). Watch design gradually moved away from the minimalism of the early 1960s, embracing more elaborate styles that played with the increasing size of watch cases. This shift was reflected in advertisements, where imagery often took centre stage over text.

-

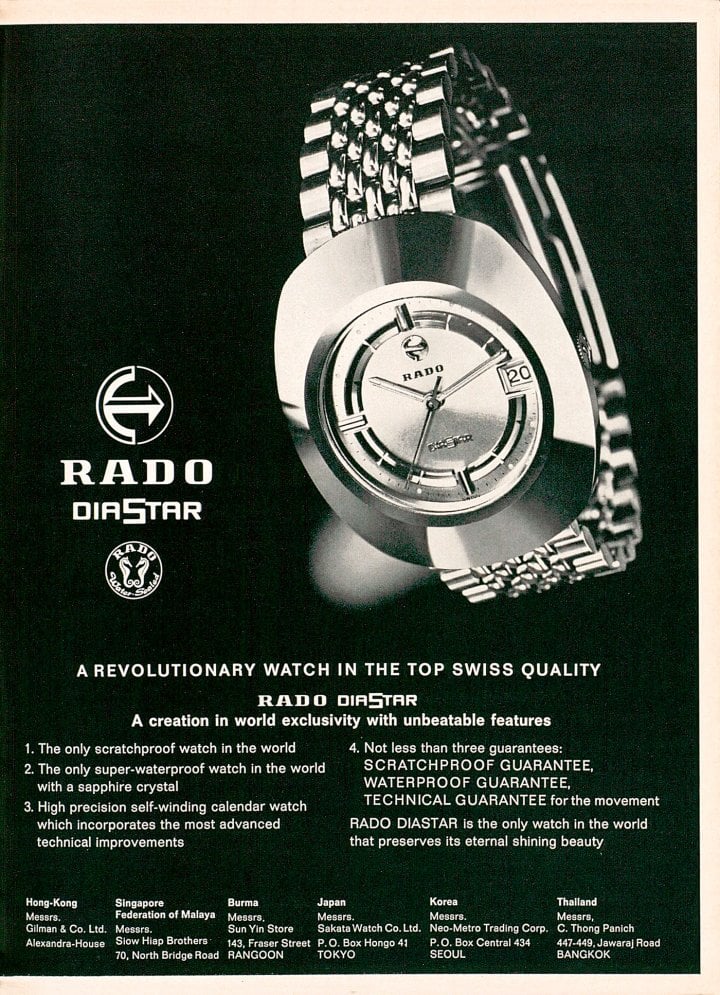

- 1964: The Rado DiaStar, promoted here as being scratchproof, water-resistant, and technically flawless, would also prove to be a trendsetter, as its oversized case inspired new styles.

-

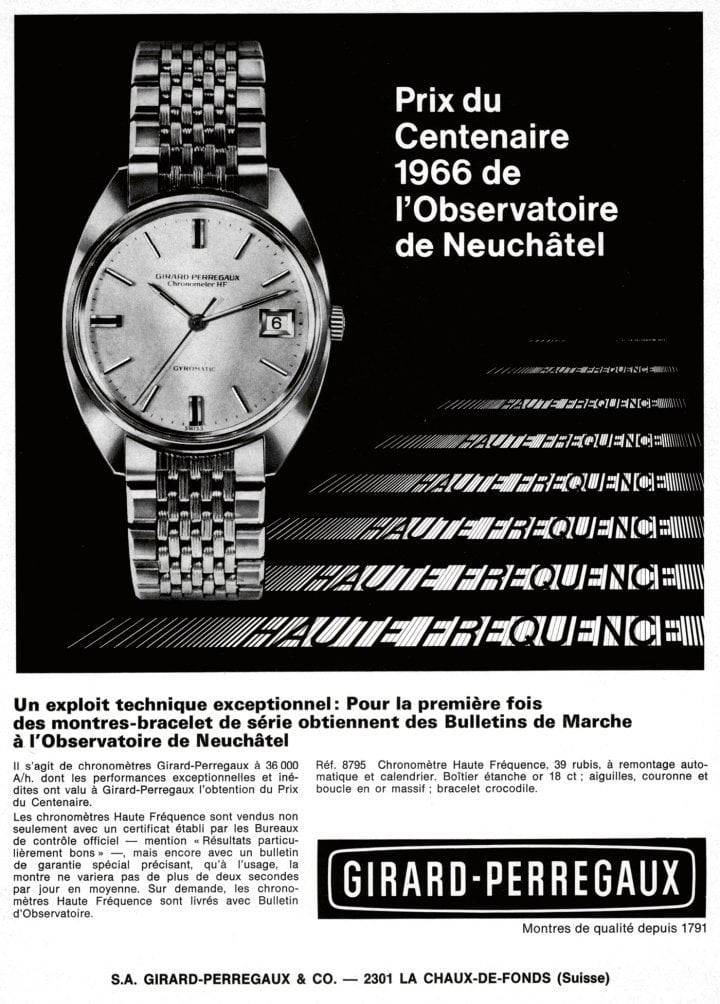

- 1966: Girard-Perregaux celebrates the success of its automatic Chronomètre Haute Fréquence. Thanks to its high-frequency escapement, it earned precision certification from the Neuchâtel Observatory, despite being series-produced.

-

- 1967: With larger watch cases came improved reliability for diving models. According to this ad, the Doxa Sub 300 “super watch” ranked among “the most accurate and durable watches in the world”.

-

- 1967: A space chronograph for everyone: thanks to NASA’s missions and Omega’s extensive promotion, the Speedmaster achieved unprecedented commercial success in the mid-to-high end of the market.

-

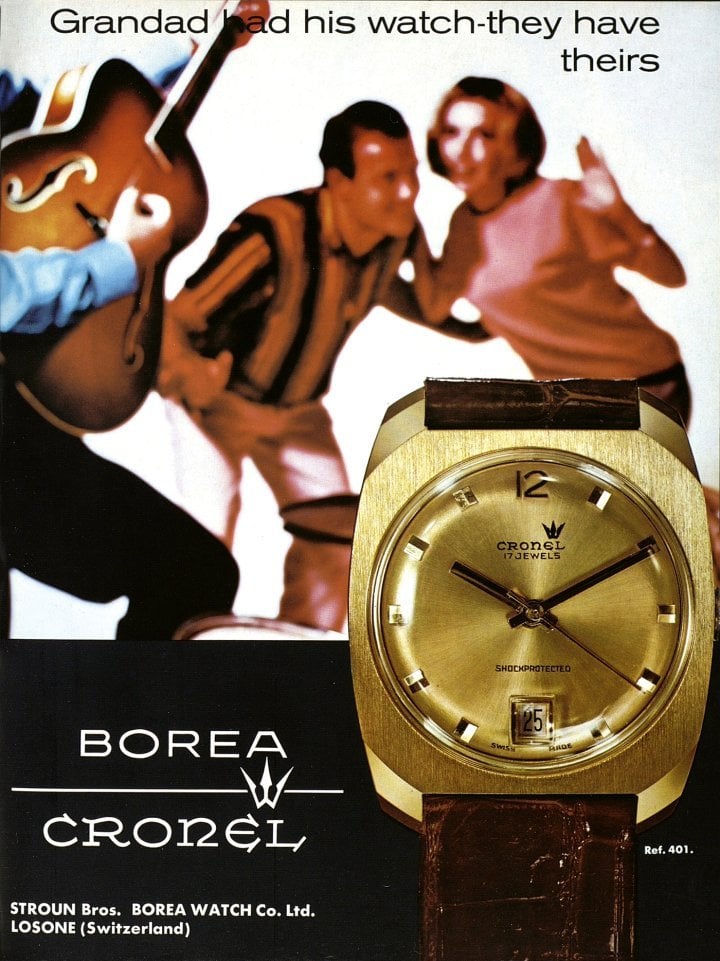

- 1968: In the mid-1960s the watch industry discovered that young people had more purchasing power than their parents did at their age. It flattered them with personalised communication, offering modern timepieces tailored to their lifestyles.

-

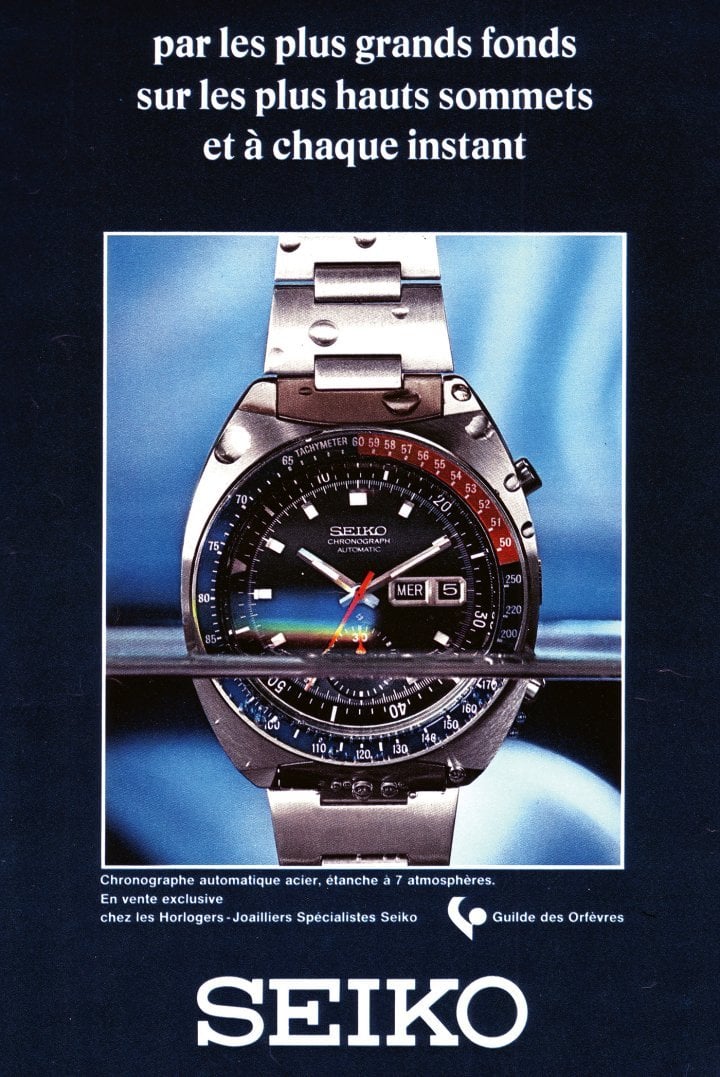

- 1969: A few years after its debut on the European markets, Seiko proved to be a formidable and innovative competitor. Its automatic chronograph became the ideal partner “in diving, on the highest peaks and at all times”.

A history of watch advertising: 1970-1979

n April 1970 the quartz wristwatch arrived in Switzerland. No fewer than 21 models were unveiled simultaneously, all powered by the Beta 21 movement from the Centre Electronique Horloger.

Initially, the revolution appeared to be purely technological, as the prices of these watches were comparable to luxury products. However, within a few short years, the cost of electronic modules plummeted, triggering a race to the bottom in which Japan and Hong Kong were the clear front-runners.

-

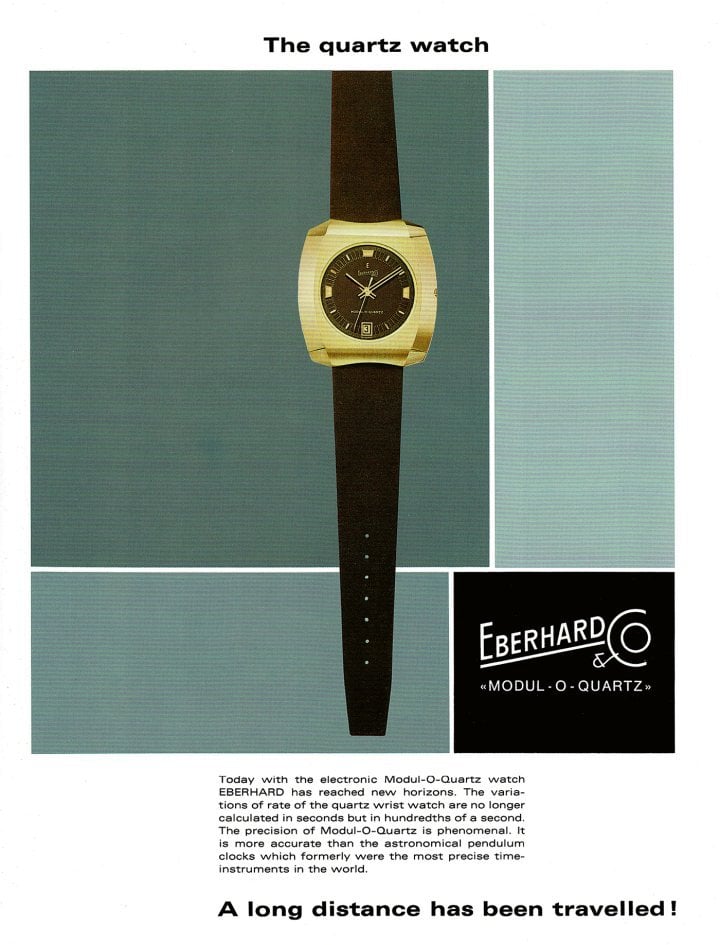

- 1970: Avant-garde technology, traditional message: Eberhard & Co. introduces its version of the pioneering Beta 21 quartz watch, highlighting its “phenomenal” precision to justify the above-average price. By 1975, this reasoning would no longer hold true.

The Swiss watch industry veered from the triumphs of 1974 – its most successful year – to the collapse of 1979, when exports dropped by 25% compared to the previous year. The impact of this commercial earthquake on specialised publications was less pronounced than that of the Great Depression in the early 1930s. Between 1974 and 1979, Europa Star saw a mere 15% reduction in the number of pages, a sign that the advertising market remained relatively robust. After all, watchmakers continued to launch a steady stream of new products, which needed to be presented to a public inevitably bewildered by the frenetic pace of change.

-

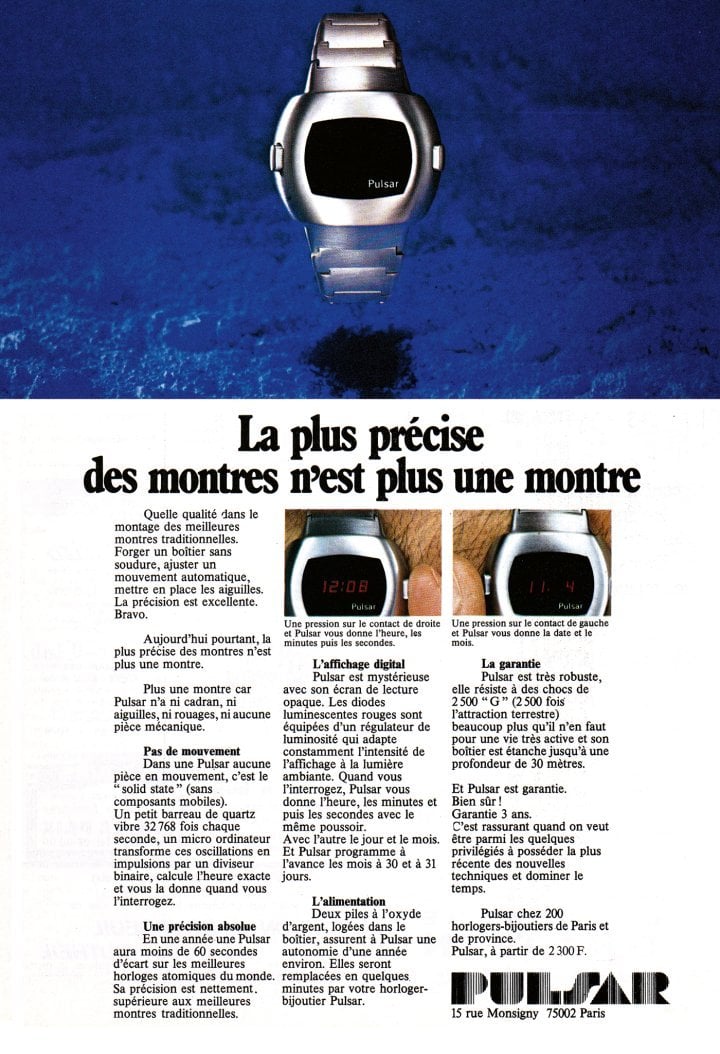

- 1972: “The most accurate watch is no longer a watch.” The first “solid state” timepiece, boasting a digital LED display and no moving mechanical parts, bore little resemblance to traditional watches, necessitating a detailed explanation of its features.

The electronic timepiece soon transitioned from analogue to LED, then LCD displays, before returning to traditional hands. In Switzerland, the traditional mechanical watch industry also underwent a transformation. Outperformed by quartz in terms of precision, the inexpensive “Roskopf” product was gradually discontinued, despite having once accounted for up to 50% of exports. The Swiss industry intensified its focus on high-end offerings, a trend that would prove irreversible in the years and decades to come.

-

- 1974: Switzerland’s leading mechanical movement manufacturer counters the rapid rise of quartz with a campaign declaring 1975 as “the year of the automatic watch” and inviting professionals to visit its booth at the Basel Fair.

-

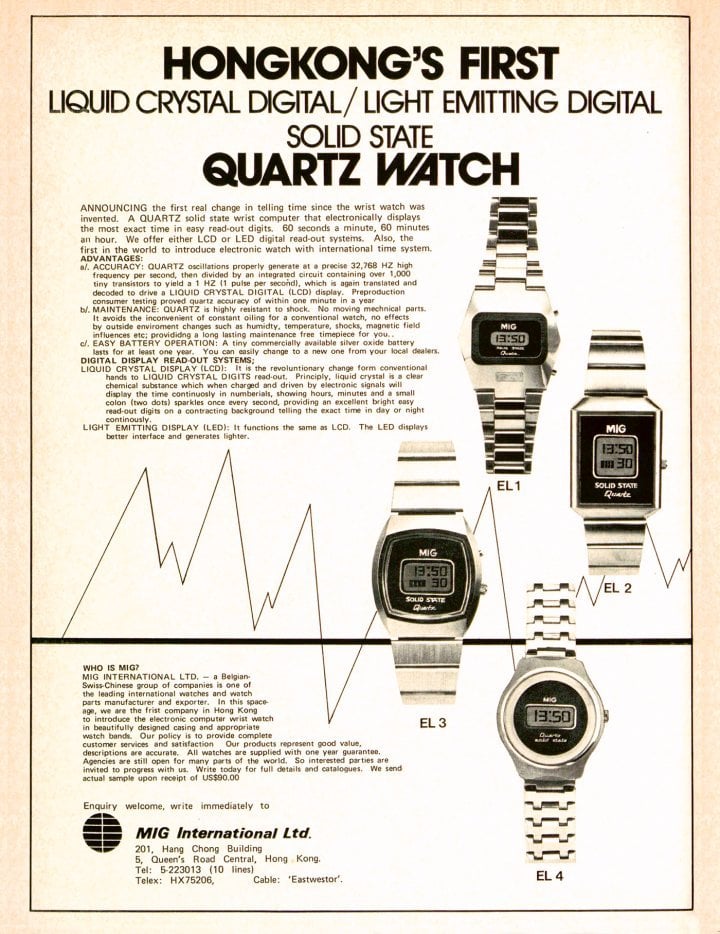

- 1974: Two major innovations in one ad: LCD technology emerges as a viable alternative to LED displays and Hong Kong begins mass-producing digital quartz watches, setting the stage for the British colony’s eventual global dominance in terms of units produced.

-

- 1975: American watch brand Timex, the market leader, enters the digital quartz sector with SSQ (Solid State Quartz). Its advertising now takes the public’s familiarity with electronic watches for granted, dwelling instead on the unique pedestal box.

-

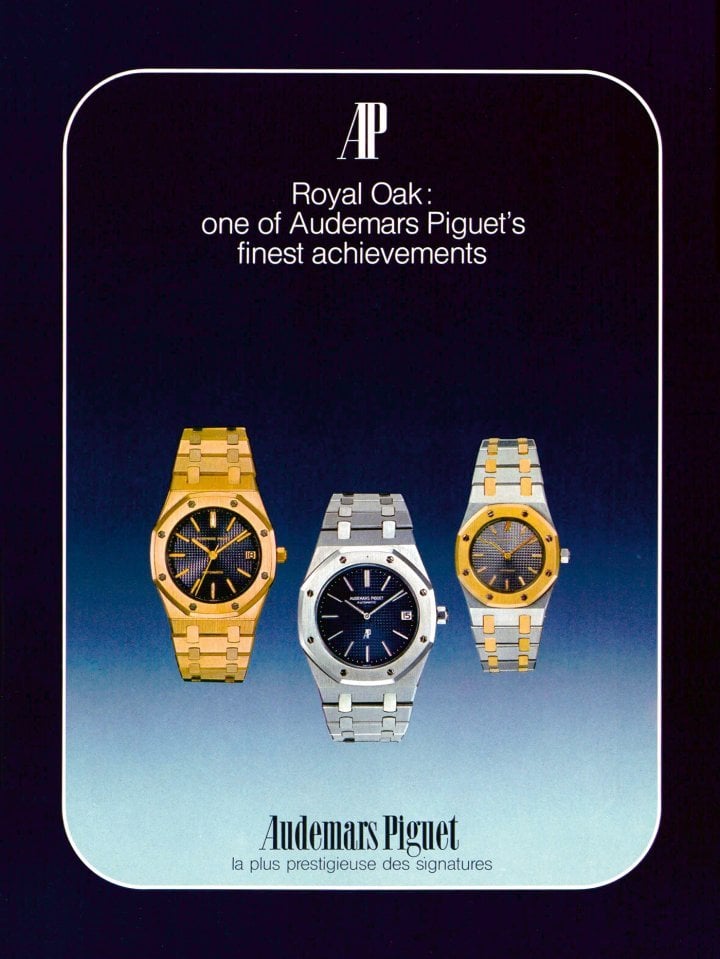

- 1977: Audemars Piguet’s Royal Oak, launched five years prior, symbolises the Swiss industry’s rejuvenation by combining luxury with sporty styling, foreshadowing what would be a wholesale shift towards medium-high and high-end production.

-

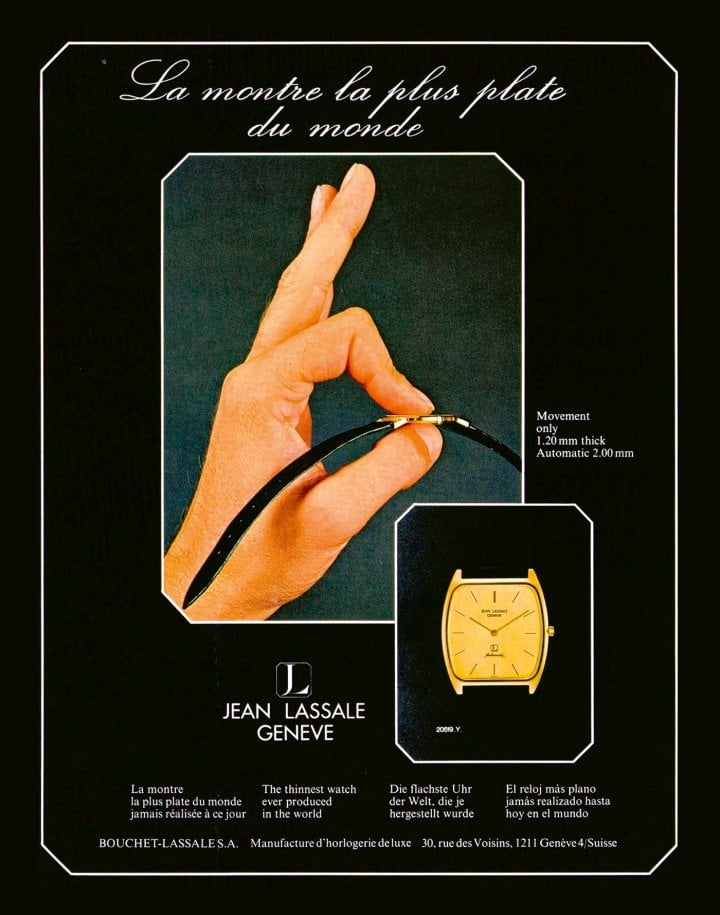

- 1977: Ultra-thin timepieces have long been a Swiss speciality. Newcomer Jean Lassale takes this to the extreme with a record-breaking design in mechanical calibres that will remain unmatched for decades. However, the massive advertising campaign fails to achieve the desired outcome, and the company goes bankrupt after just six years.

-

- 1979: Fashion brands expand into watchmaking. Following in the footsteps of Roberta di Camerino, Gucci and Dior, Hermès enters the scene with the Arceau. The increasingly compact quartz movements make it possible to produce a ladies’ version.

A history of watch advertising: 1980-1989

watch: the name alone evokes not just a manufacturing and aesthetic revolution, but also a commercial and lifestyle phenomenon, the rebirth of the Swiss watch industry after years of struggle, and new, creative, non-conformist communication methods.

The enormous yellow watch stretched across a Frankfurt skyscraper’s façade, the vibrant and playful advertising, and the association with youth-centred events like the World Breakdance Championship were among the initiatives that had the most significant impact on the public.

-

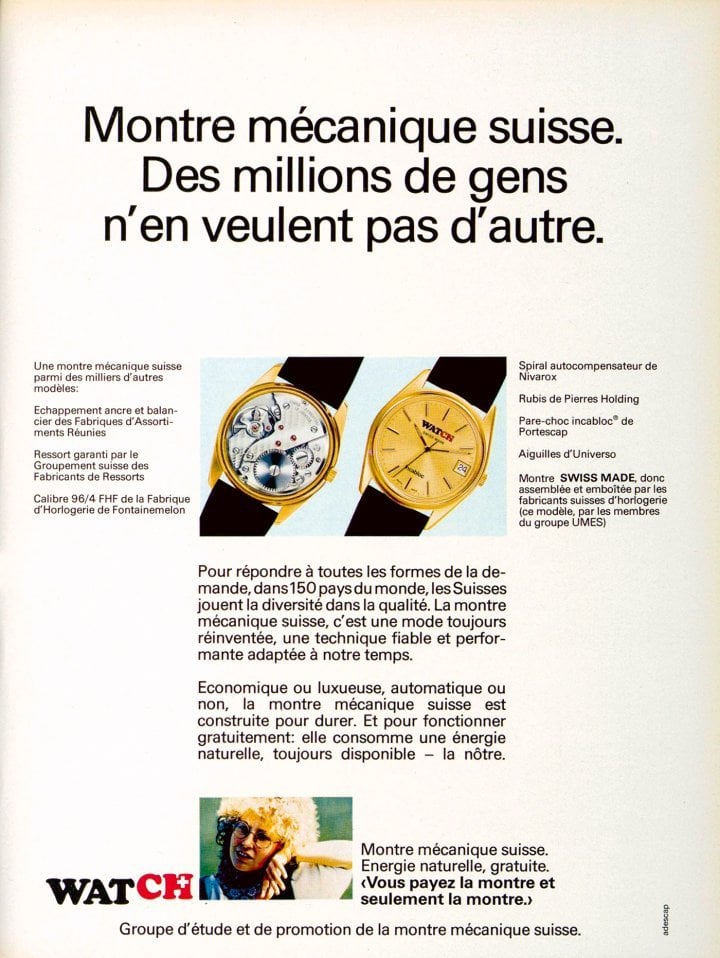

- 1980: To defend the mechanical watch from the onslaught of quartz, the promotion group set up by the Swiss industry played the cards of durability and “free energy”. No need for batteries: “You pay for the watch and only the watch”.

The origins of Swatch lie in the technical solutions that enabled Switzerland to win the contest with Japan to create the world’s thinnest timepiece. The success extended beyond a single product and revitalised the entire Swiss industry, which once again became a major player across all sectors. While the plastic watch shattered conventions, manufacturers with a rich heritage – including IWC, Ulysse Nardin, Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet – introduced both traditional and innovative complications that rekindled interest in mechanical timepieces.

-

- 1980: 1980 saw the end of the race to create the world’s thinnest watch. Switzerland overtook Japan with a design in which the case was an integral part of the movement. The ad describes the first three versions of the Delirium, with victory ultimately going to the Delirium IV, the first and only timepiece in history to be less than one millimetre thick.

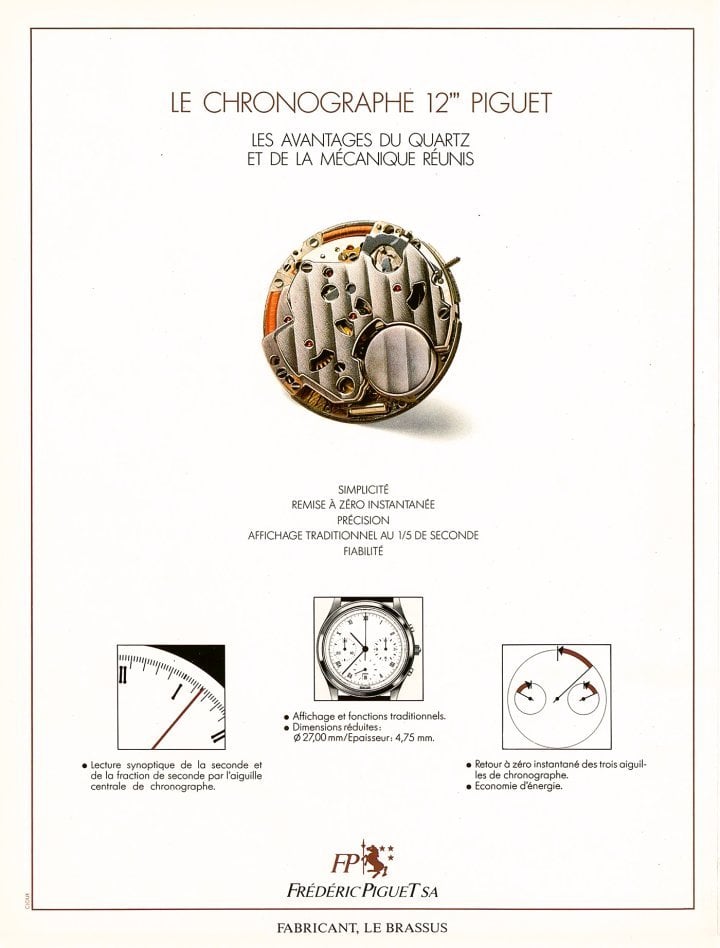

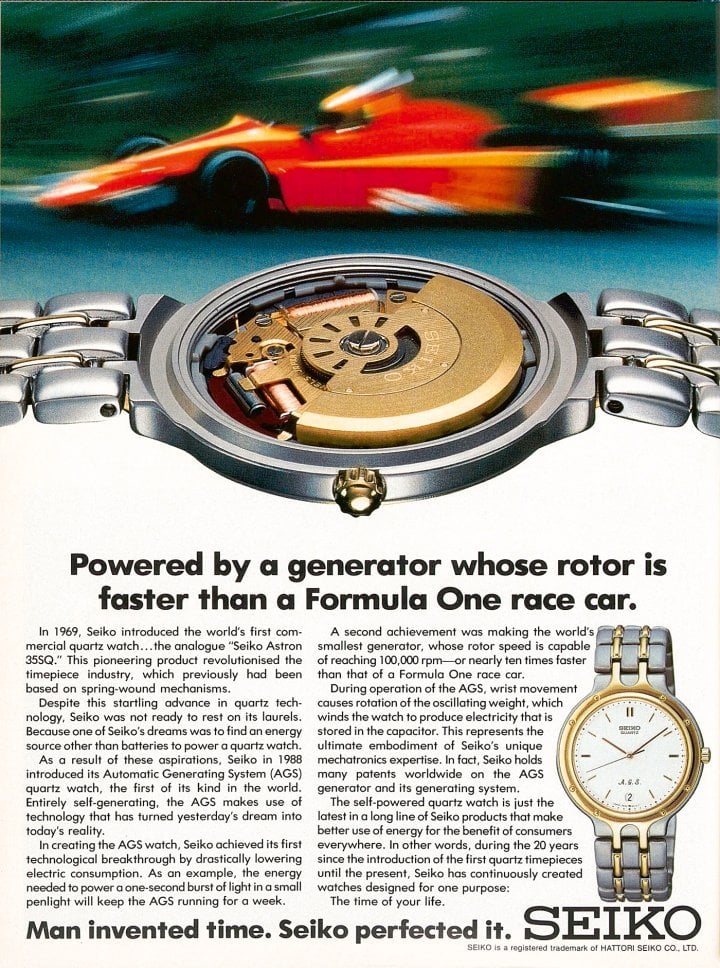

Quartz movements were not confined to just Swatches and multifunction digital watches. Some made it into high-end products (Frédéric Piguet, Girard-Perregaux), while others were combined with automatic winding to eliminate the need for a battery (Seiko, Le Phare). In most cases, advertising took a traditional approach. Because images alone were insufficient, text was necessary to emphasise the benefits of technological advances. Finally, advertisements also showcased the introduction of novel materials such as titanium, high-tech ceramic, tantalum and meteorite.

-

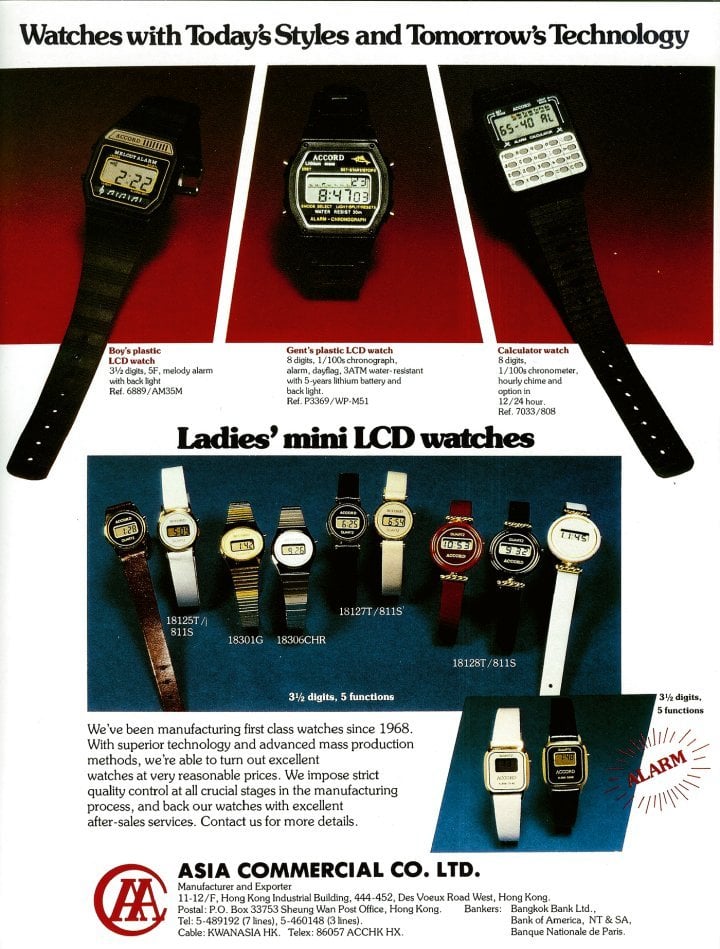

- 1983: Digital LCDs were becoming more affordable and feature-rich. The Asia Commercial (Hong Kong) range offered models with calendar, chronograph, simple or musical alarm and calculator, powered by batteries that provided five years of autonomy.

-

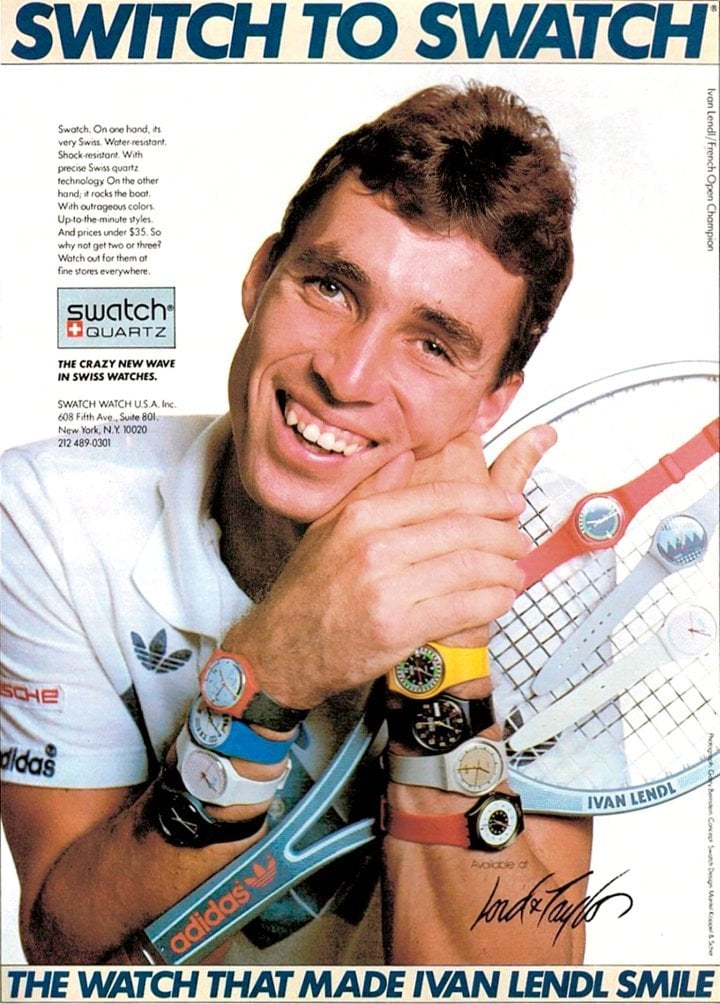

- 1985: This ad, which is typical of Swatch’s communication style, features a famous testimonial. Ivan Lendl, the notoriously and perennially grumpy world number one tennis player, cracks an amused smile at the “crazy new wave in Swiss watches”.

-

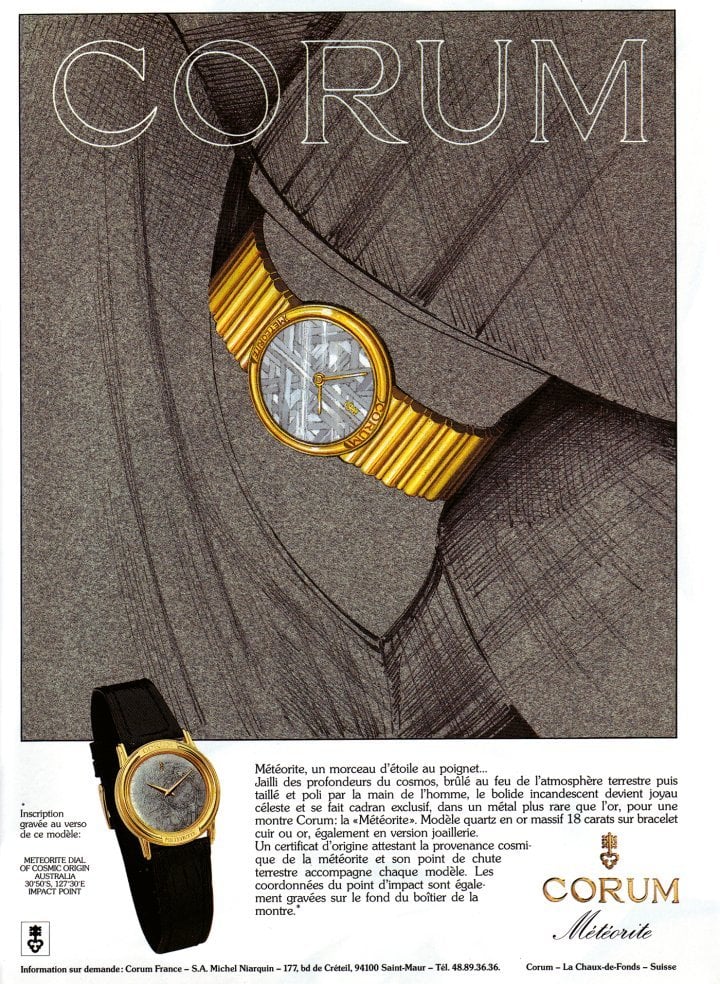

- 1986: “A fragment of a star on the wrist”. Among the watch industry’s innovations, meteorite was the only one accompanied by a “certificate of cosmic origin”. Here, Corum stresses that the material used for the dial is “rarer than gold”.

-

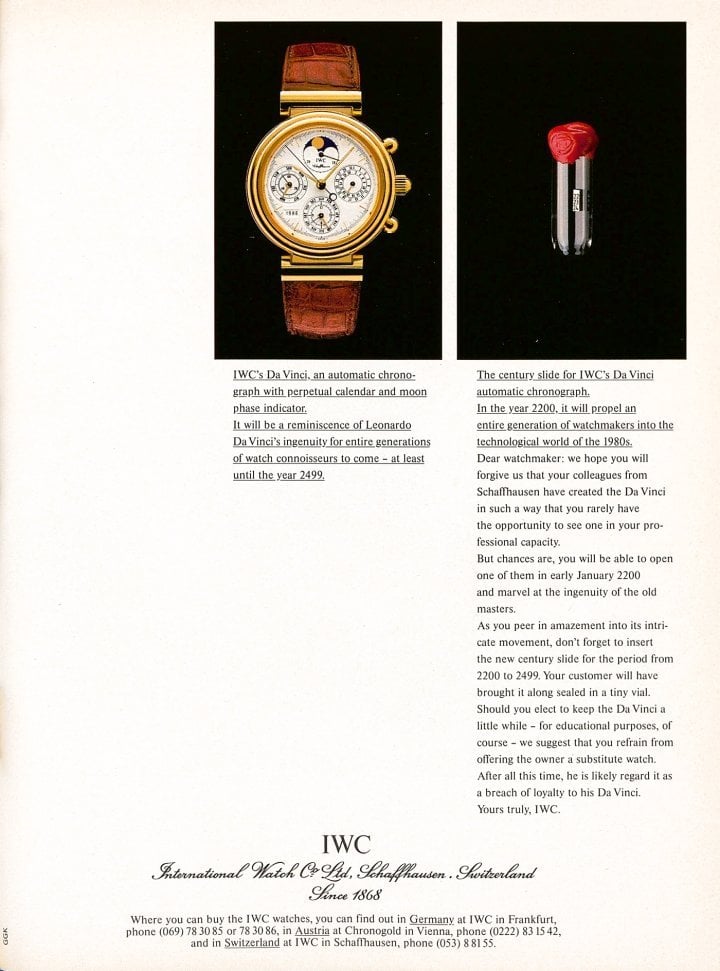

- 1986: The second half of the decade brought mechanical complications back into vogue. The text dedicated to the Da Vinci chronograph with perpetual calendar refers to the watchmaker who will have to replace the century indication bar in 2200.

-

- 1989: Quartz doesn’t necessarily mean cheap. Movement manufacturer Frédéric Piguet introduces a high-quality hybrid chronograph that combines electronic and mechanical functions.

-

- 1989: The first quartz automatic timepiece realises the dream of a battery-free electronic watch, powered by the movements of the arm. The ad emphasises that the rotor’s speed is ten times faster than a Formula 1 race car.

A history of watch advertising: 1990-2000

omputer-aided design (CAD) democratised mechanical complications, making them accessible to numerous manufacturers and favouring those who chose to develop in-house movements.

The desire to become independent of suppliers and the resulting consolidation in the latter part of the 20th century changed the face of the sector, expanding the portfolios of large groups like Swatch, Richemont and LVMH.

-

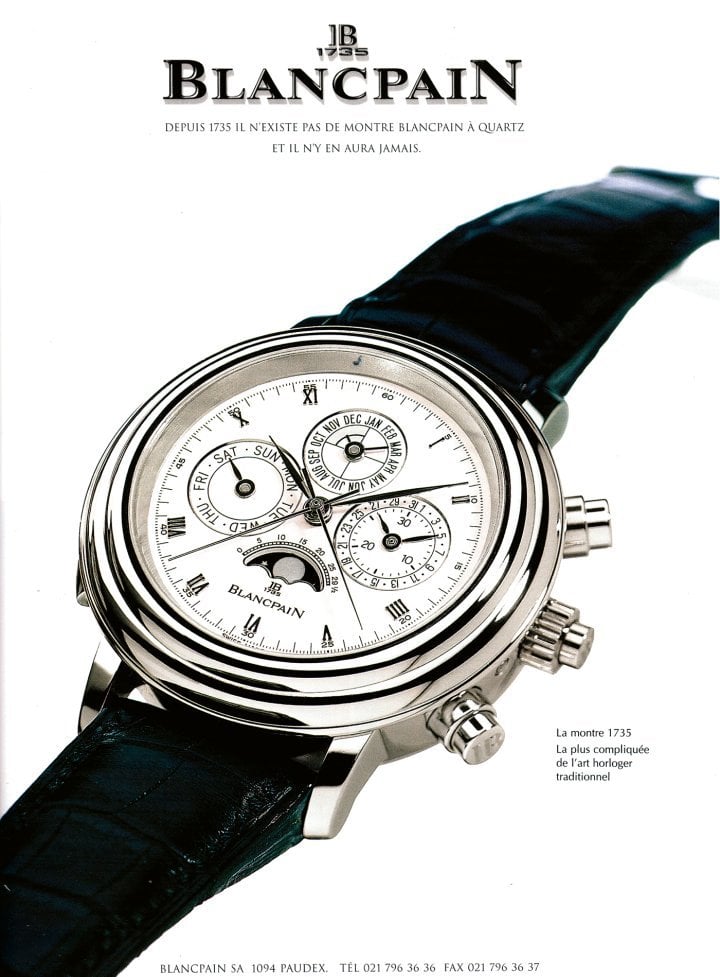

- 1991: The era of record-breaking mechanical supercomplications begins. Blancpain’s 1735 model, named after the company’s founding year, combines previously introduced movements in one watch. The image dominates the ad, relegating the brief description to an afterthought.

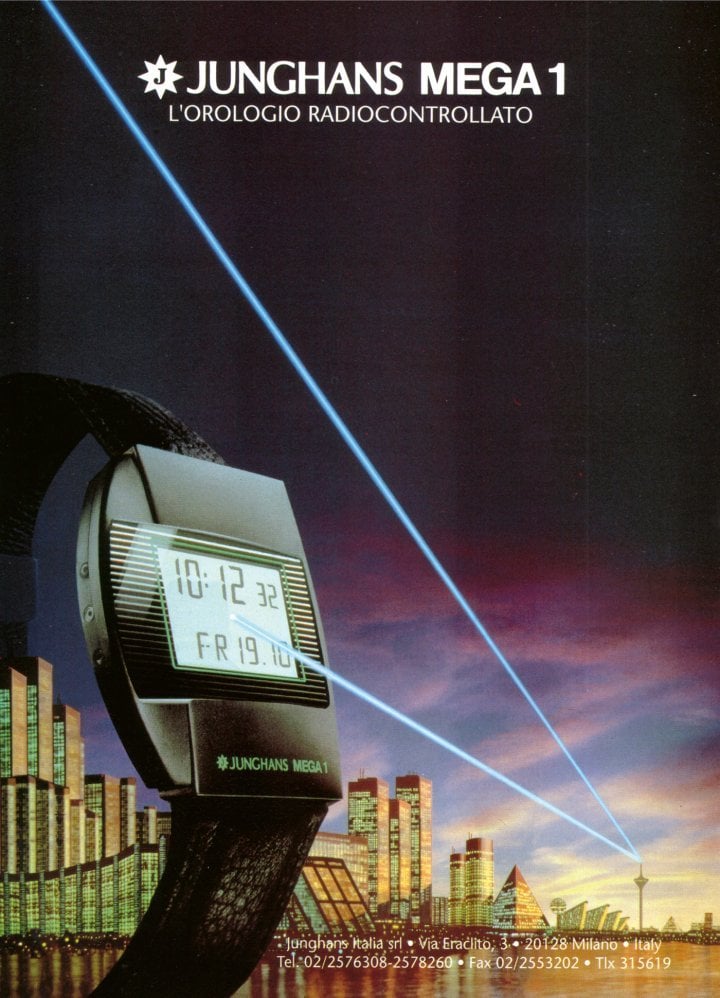

Brands including IWC, Audemars Piguet and Panerai introduced “XL” models, initiating a style revolution. Their success extended the trend to all segments of the market. In answer to the unrivalled prestige of mechanical movements, quartz technology offered increasingly sophisticated alternatives, including radio-controlled precision (Junghans), electronic chronographs with automatic winding (Seiko), touchscreens (Tissot), wrist cameras (Casio) and automatic watches with digital displays (Ventura).

-

- 1991: The Junghans Mega 1, a digital radio-controlled watch, is presented in a futuristic setting, capturing the dream of absolute precision. This text-free ad, perhaps inspired by science-fiction film sets, seems to imply that commentary is superfluous.

In the early 1990s, Swatch novelties sold like hot cakes and became the subject of speculation – not unlike the situation we’re seeing in 2023. Advertising held up a mirror to an industry bursting with health. Watch brands had significant resources to fund advertising campaigns and spared no expense, filling specialised and general-interest magazines with creative and diverse messages. Some brands leveraged prestigious endorsements while others exploited the appeal of tradition. Some focused on technical innovation, others the lure of limited editions, striking slogans or surprising imagery.

-

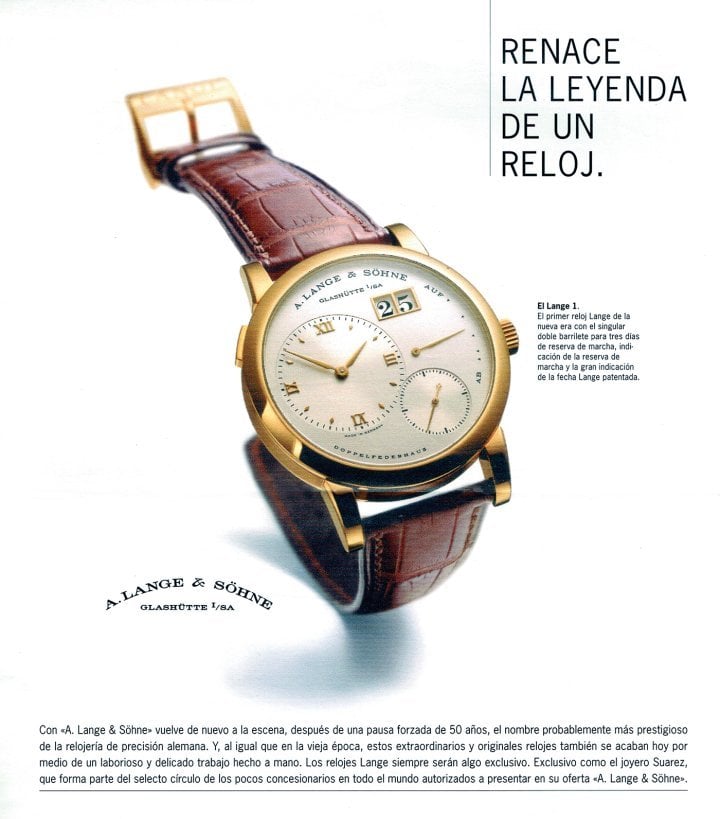

- 1994: The reunification of Germany and investments from the Vendôme group (later Richemont) paved the way for the revival of historic Glashütte watchmaker A. Lange & Söhne. This Spanish magazine ad showcases the iconic Lange 1.

-

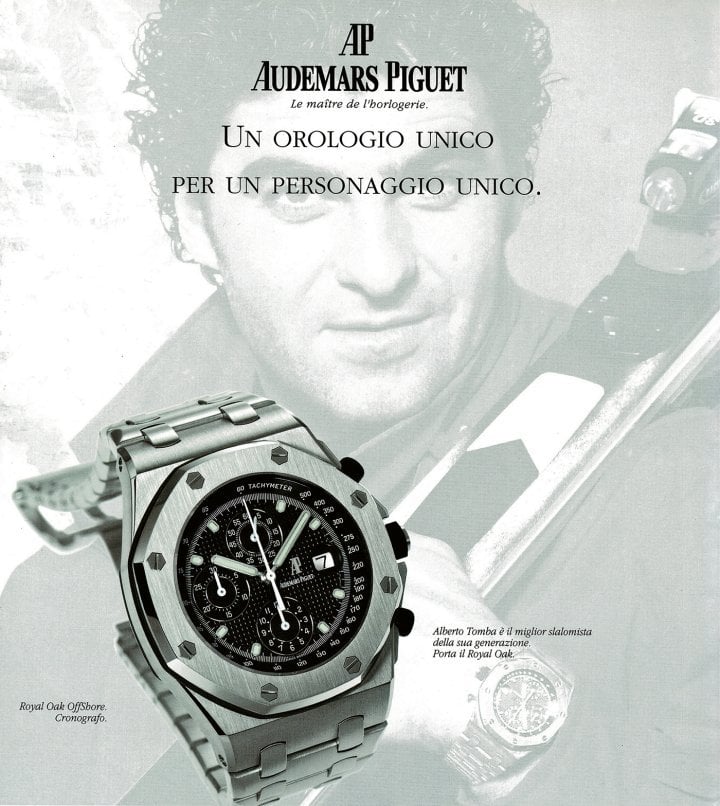

- 1994: Audemars Piguet’s Royal Oak Offshore chronograph, one of the first oversized models of the 1990s, is launched with the endorsement of Italian ski champion Alberto Tomba, a well-known figure among sports enthusiasts.

-

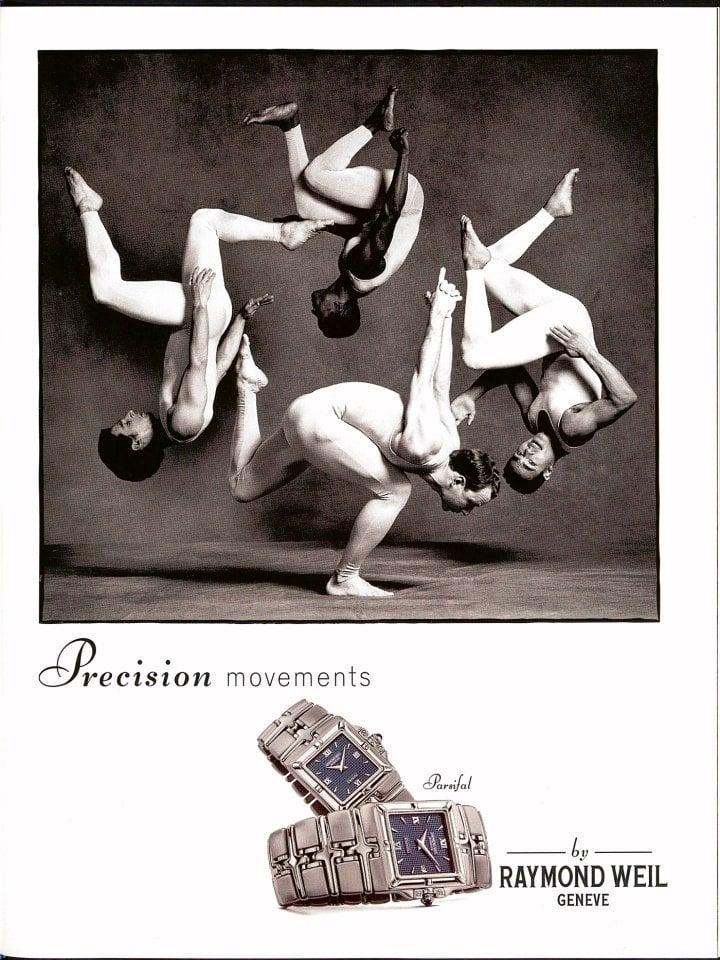

- 1995: The image of gymnasts seemingly suspended in mid-air offers an alternative interpretation of the expression “Precision Movements” by Raymond Weil.

-

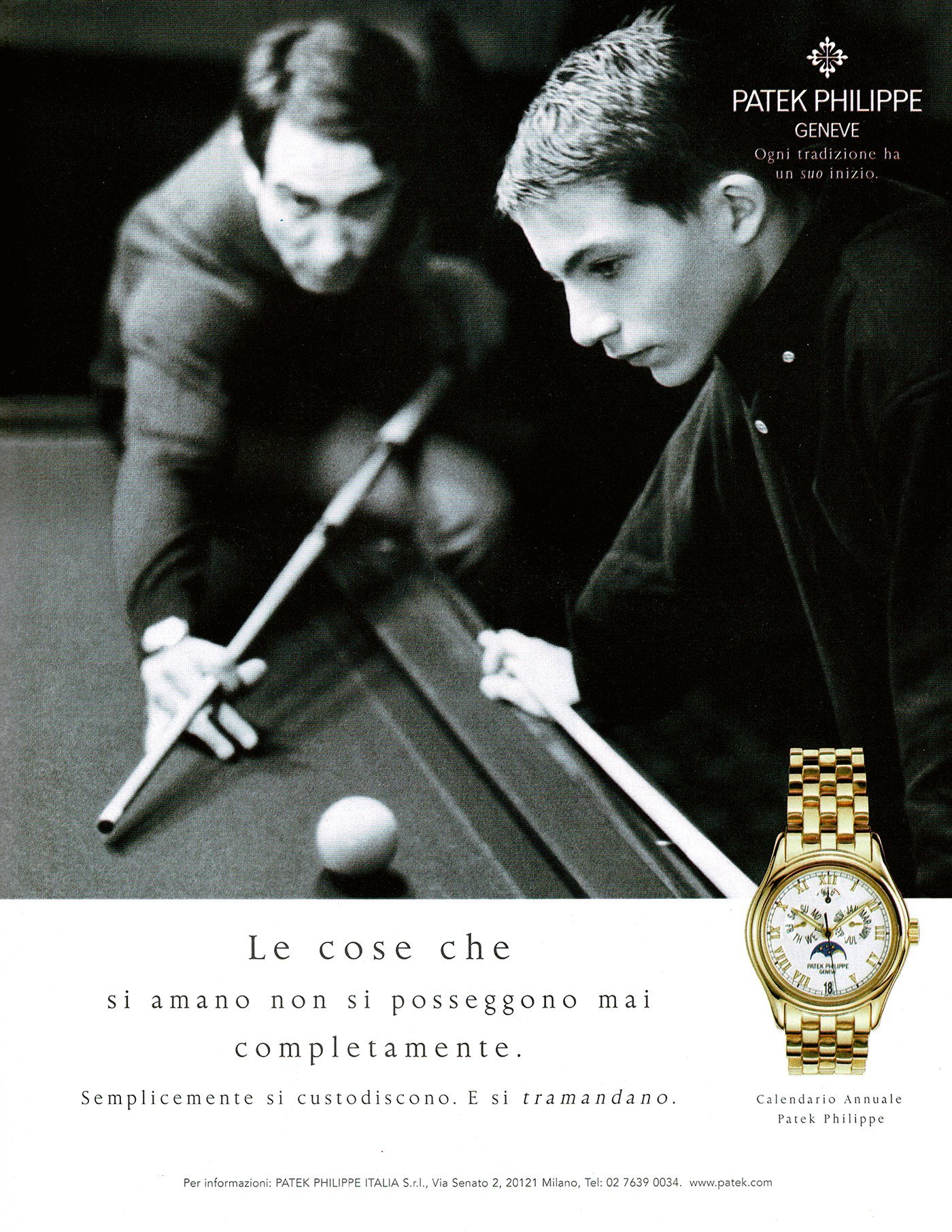

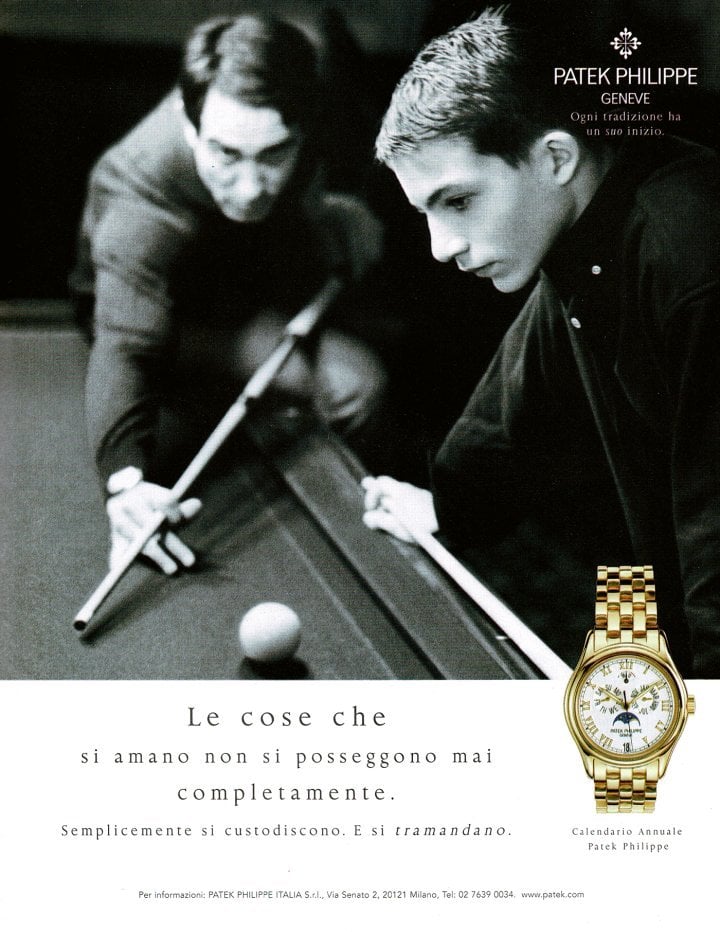

- 1996: Patek Philippe’s “Generations” campaign, created by the company’s London agency, launches with black and white photographs of parents and their children, accompanied by text that emphasises the value of tradition across generations.

-

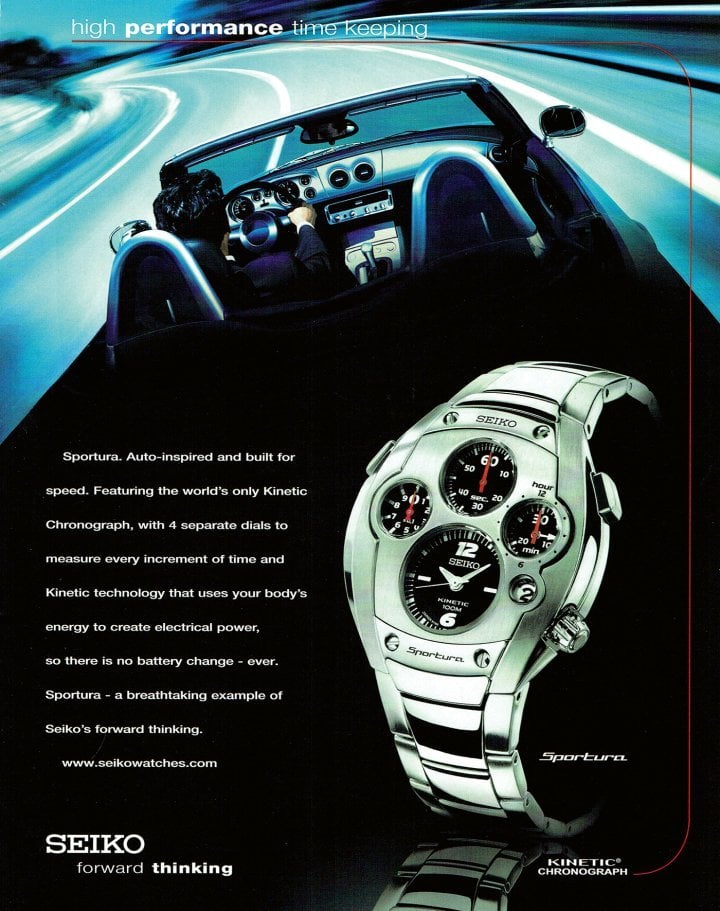

- 1998: The arrangement of the counters on the Sportura’s case resembles the dashboard of a sports car, like the one in the background, suggesting that the name of Seiko is synonymous with innovation.

-

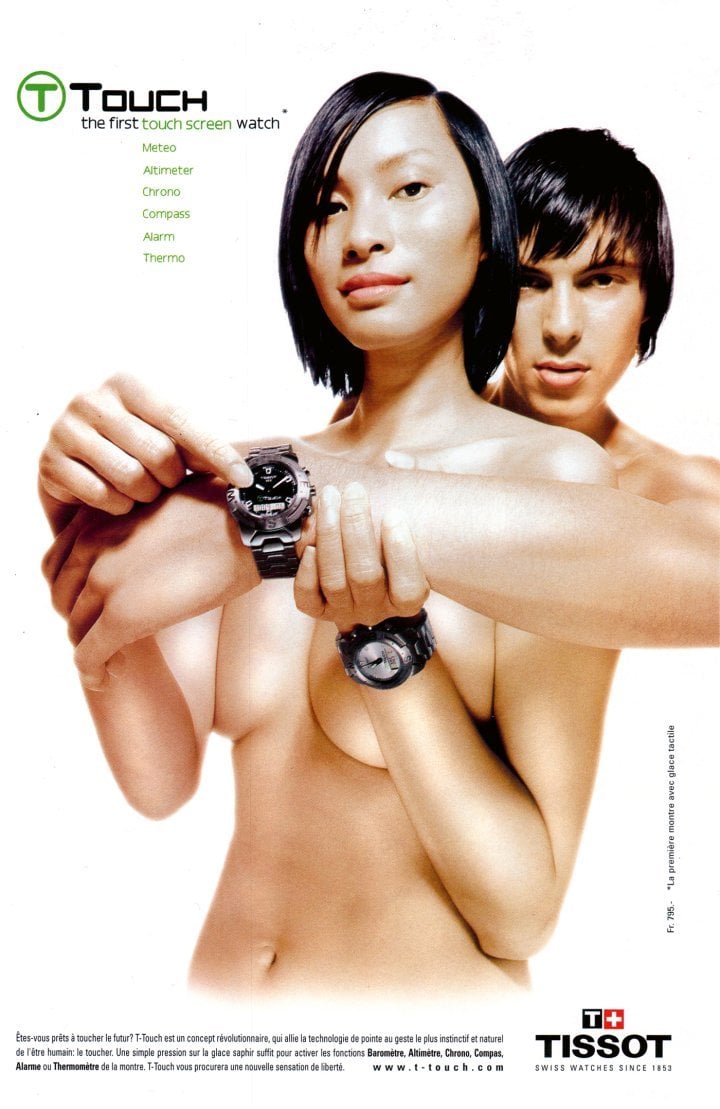

- 2000: Pre-smartphone, the watch industry embraced touchscreens, targeting a young demographic as the ideal customers for innovative products. Swiss manufacturers witness a shift in the market’s centre of gravity towards the Far East.