Greubel & Forsey

Serendipity determined that the destinies of Robert Greubel and Stephen Forsey would cross in Switzerland, but neither of these two men is originally from this nation. Robert Greubel was born in 1960, in France, where his watchmaking father initiated him at a very early age into the mysteries of the métier. After having studied watchmaking in Morteau, followed by a stint in the family workshops, and then specializing in complicated timekeeping, Gruebel joined IWC as a prototype maker. He later moved to Renaud & Papi (which today belongs to Audemars Piguet) where he rapidly became Executive Director and Associate.

As for Stephen Forsey, he was born in 1967 in St-Albans, not far from London, a city famous for its many marine chronometers that were manufactured in the English capital. He was also in-itiated into the art of mechanics as a young man by his father, who was a passionate fan of avi-ation. After studies in watchmaking at the Hackney Technical College in London, Forsey devoted his time to restoration at the famous London brand, Asprey. Following some time spent at Wostep, with courses in complicated mechanical timekeeping, Forsey also joined the team at Renaud & Papi. Grand sonneries, minute repeaters, carillons, tourbillons, and perpetual calendars all passed through his hands.

In 1999, the two friends decided to stretch their own wings. The objective was to invent and create new movements. In 2001, they founded CompliTime SA in La Chaux-de-Fonds, a company dedicated to the development of complicated movements for some of the largest names in the Swiss watch industry.

At the same time, they worked to launch their own brand, which they named Greubel Forsey. Their first product saw the light of day in 2004. That year, they exhibited at BaselWorld for the first time under their own brand name, and presented their first invention: the Double Tourbillon 30°. A true and exciting Premiere for the duo.

The Double Tourbillon 30°

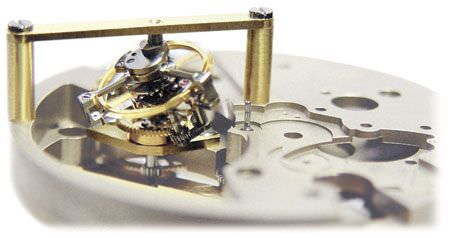

What the two men presented was, in fact, a world first for a wristwatch. Inside a large carriage (15mm in diameter), which rotated in four minutes, was a smaller second carriage, which supported the escapement and the balance spring, and which was inclined at 30° in relation to the first. Its rotation was one minute. In all, the two carriages were made up of 128 different elements for a total weight of 1.17 grams.

The 30° angle was chosen so that the balance would never be in a flat position. It also allowed the designers to use a larger balance, therefore a priori permitting for better adjustments, with a larger moment of inertia. Moreover, these two rotations, of one and four minutes, allowed a homogenous blending of the balance’s pos-itions, decreasing the probability that the balance would find itself in an unfavourable place. This would not have been the case, for example, with two respective rotations of one minute, or if the cycle were shorter. Thanks to the 30° inclined angle of the second carriage, the balance’s movement forms a cone; in its horizontal pos-ition, the balance will therefore never be flat. Thus, the balance will not suffer violent devi-ations in operation or in amplitude, between flat and vertical positions.

But, once the watch is on the wrist, the balance will naturally be subjected to changes in position. The size of the balance, and its system of variable inertia, will then compensate for these changes.

With this exceptional creation, and its magnificently finished architecture, Greubel Forsey have brought back the usefulness of the tourbillon, which, as we know, had been originally conceived by Breguet for use in pocket watches, but which has also remained relatively non-functional for wristwatches. To give an idea of comparison, the working deviation of a classic tourbillon, measured in six positions, is +/- 7 seconds, while that of the Greubel Forsey tourbillon is of the order of +/- 3 to 3.5 seconds.

The mysterious EWT abbreviation

This performance was made possible thanks to the creation of a unique tool that combined basic research, development, and adjustments. The duo named it EWT®, for Experimental Watch Technology®. A veritable laboratory for horological research, the EWT allows its designers to conduct many original experiments in an independent manner, to carry out tests, and to proceed towards complete homologations.

The EWT is, in a certain manner, a ‘funnel’ that passes through three specific stages: invention/conception, development /construction, and validation/homologation.

Very open and approachable since the beginning (“We wanted to allow the maximum number of ideas to be tested,” say the two men), the EWT allows, in a continuous flux, prototypical concepts to filter in, the realization of 3D models, the creation of principle prototypes, and finally the production of the product in an experimental stage. Corrections, improvements, tests, simu-lations, and refinements all lead to the fabrication of one prototype after another, gradually ending with the final validation of the invention.

Three projects in the pipeline

As of today, three projects have passed through the ‘tube’ or the technological platform of the EWT: the Double Tourbillon 30°, that we have just described and that, at the end of the process, is now in its production stage; the Differential Spherical Quadruple Tourbillon, which having passed the development and construction phase is now in the homologation stage (its launch is expected in 2008); and finally, the 24 Seconds Inclined Tourbillon, which is in the initial stages of development and construction.

One of the main advantages of the EWT is the possibility that it can lead to a considerable number of experiments and observations that all nourish the realm of timekeeping invention.

Armed with the experience acquired with their first Double Tourbillon 30°, Greubel and Forsey are striving, with their second watch, to reach absolute theoretical precision. Their idea is to associate four tourbillons in a common system, whose core is constituted of a spherical differential that can continuously manage and redistri-bute the energy present. Thanks to this micro-mechanism, a perfect correction of the smallest working variations can theoretically be achieved, “like the differential bridge that we find on a car’s wheels, which distributes the torque between the two ends while allowing different rotational speeds,” explain the designers.

The Differential Spherical Quadruple Tourbillon

The 24 Seconds Inclined Tourbillon

The research carried out on this Differential Quadruple Tourbillon has led to the launch of Greubel Forsey’s third project, the 24 Seconds Inclined Tourbillon. The approach here is totally different, but the goal is the same: to achieve the highest level of chronometry possible. It involves exploiting another opportunity offered by the rotating carriage, which is to attain the highest rotational speed possible. The more the ro-tational speed increases, the greater is the ability of the regulating organ to escape “the critical positions due to terrestrial attraction” in a sort of “race towards the change of positions”.

Yet, the challenges are many, notably the large energy consumption at the start-up and the additional mechanical constraints. It has also been necessary to conduct advanced research into the weight of the component parts (Avional aluminium alloy for the tourbillion pillars; ti-tanium for the carriage bridges), as well as into the gearing systems. In this area, the very special geometry of the inclined gearing of the satellite pinion has been the subject of much research. Architecture and theatricality

The high speed attained by the 24 Seconds Inclined Tourbillon (one rotation takes 24 seconds instead of the habitual 60 seconds) allows for significant improvement in the performance of a single tourbillon. And, as is the case for the brand’s other movements, the architecture of this tourbillon is derived directly from the technical functions and “displays the same determination to spectacularly showcase” the tourbillon’s mechanism.

At Greubel Forsey, the same rigour is at work in both the mechanical construction as well as the organization of the visual and functional space of the movement and the case. Everything comes together so that the “readability of this watchmaking genius” is immediately apparent. Thus, the arrangement of the various elements is prepared in such a way that it “softens the complexity” of the piece with easy and rapid visual access to the heart of the systems.

The 24 Seconds Inclined Tourbillon

Example of the Opus 6

This approach is also brilliantly illustrated in the Opus 6, created this year for Harry Winston. In its own way, this timepiece, whose case resembles those of Harry Winston’s Ocean collection, is a perfect example of Greubel Forsey’s singular aesthetic and technical approach to timekeeping. Integrating their Double Tourbillon inclined at 30°, they have cleared it from all superstructure, leaving it to beat and rotate freely, isolated at the back of the case. The entire gear train has been concealed under a large bridge, leaving only the balance wheel to move freely above the plate. The result is a very theatrical piece, one that is structured and stepped over several levels (whose forms evoke the symbolic play of the number ‘6’), and which comprises interesting sub-dials. The small seconds is on the ‘second level’ at 11 o’clock, and the hours and minutes are on the ‘third level’, revealed in two sub-dials on a co-axial disc located at 2 o’clock.

This timepiece presents one of the immense qualities of watchmaking as envisioned by Greubel Forsey: the exceptional level of the finishing. The purism of the mechanisms is taken to even greater heights by the manual care given to smoothing the edges, polishing, and chamfering of even the smallest component part. There is quite evidently no compromise in the attention to detail.

The three major inventions presented since their grand entrance in 2004 have demonstrated a form of exclusive watchmaking at Greubel Forsey, an art of timekeeping that draws its aesthetic strength from the purest forms of its own technical nature. It is unlike any other, with a force derived from the proper genius of its two creators. The remarkable journey of Robert Greubel and Stephen Forsey deserves the respect of all those who are impassioned by the art of exceptional timekeeping.

Source: Europa Star August-September 2006 Magazine Issue