n the spring of 1900, a Greek sponge diver diving along the steep coastline of the small island of Antikythera sees what he thinks are human bodies lying on the seabed. He dives again and brings up the hand of a bronze statue. He has just discovered, at a depth of some 60 metres, the shipwreck of an ancient Roman vessel which in around 50 BC (a date determined by a retrieved coin) was transporting a cargo of “luxury products”.

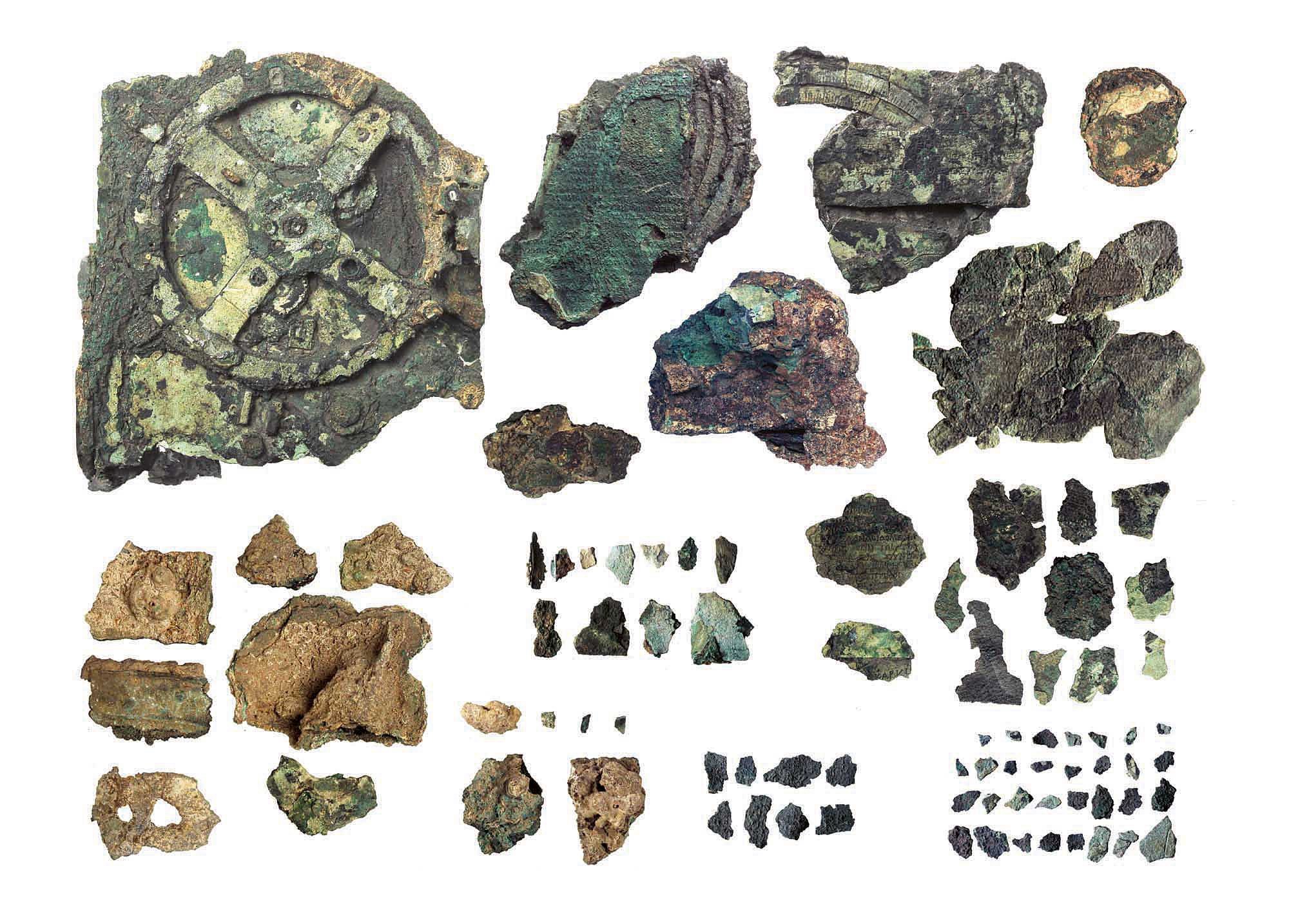

Among them, between magnificent statues, valuable artefacts, jewellery, coins, crockery, glassware, surgical instruments and other items (which now occupy three rooms in the National Archaeology Museum in Athens), the excavation work rapidly conducted by the Greek navy also brought up a small, mangled mass of bronze corroded by the sea, with strange forms apparently embedded in it. A mystery. What on earth could it be?

In this lump of metal a Greek archaeologist made out fragments of gear wheels and bits of inscriptions. And in 1905, a German scientist was the first to opine that it was, in all probability, a planetarium. But without the requisite scientific means to investigate, the lump of metal remained a mystery until the mid-20th century.

From 1959 and into the mid-1970s, D. J. de Solla Price, a physicist and science historian at Yale University, made a closer examination, exploring the secrets of the mechanism’s 82 indexed fragments using gamma rays. He discovered the highly complex architecture of a mechanism composed of around 30 gear wheels, axes, drums, mobile hands and dials engraved with more than 600 inscriptions and astronomical signs.

He published his results in 1974 in a landmark work, Gears from the Greeks. He had succeeded in determining that the Antikythera mechanism was worked by a crank and that at least one of its gear trains corresponded to an ancient lunar and solar cycle known to the Babylonians.

In 1976, Jacques Cousteau explored the wreck in turn, retrieving various artefacts including statuettes. In the meantime, research on the mechanism came to a halt as it proved impossible to isolate fragments of the machine without damaging it irreparably.

Then in 2000, two astrophysicists, Mike Edmunds from the UK and John Seiradakis of Greece, together with an English mathematician, Tony Freeth, thought of investigating the mechanism more closely using a computed tomography scanner, a very high-resolution X-ray machine. But to do this, they had to build a scientific device weighing more than eight tonnes.

-

- Details of the cogs and inscriptions on the fragments of the Antikythera mechanism scanned by tomography

A multidisciplinary team of specialised companies, astronomers, physicists, palaeographers and archaeologists, brought together with the help of the universities of Cardiff, Athens and Thessalonica, got down to work. Their CT scanner made it possible to produce three-dimensional images accurate to within 50 micrometres. Exploration began in the autumn of 2005…

Mathias Buttet tells what happened next…

Mathias Buttet, a qualified engineer, has been at the helm of the R&D department at Hublot since 2010. We have him and his teams to thank for such items as Magic Gold, which is produced solely in the R&D laboratory, as well as the exclusive, brightly coloured ceramic materials in red and other colours.

A fervent materials enthusiast, he also recovered old machines from the former USSR to produce his own sapphire crystal masses. In another section of the R&D department, you might chance upon two underwater drones under construction, being refined by postgrad students from the EPFL (a prestigious Swiss university), and a very curious object resembling a many-sided satellite, the purpose of which is still a secret. All we can say is that it might be the Antikythera mechanism of the future.

The “Antikythera mechanism!” When Mathias Buttet learned of its existence, in 2008, in an article co-authored by the Greek physicist and astronomer Yanis Bitsakis in the popular French science magazine, Science et Vie, he was gripped. “This ancient machine seemed to challenge everything I knew about the history of mechanical science.” He contacted the author and spent a week with him in Athens trying to comprehend the abilities of the machine and listening to the arguments situating its origins around 200BC. “He was right. The Antikythera mechanism, often described as the first ancient analogue computer, bears incredible witness to human ingenuity. That experience was a real lesson in humility for me as an engineer.”

-

- Mathias Buttet has been at the helm of the R&D department at Hublot since 2010.

At that time, in 2008, he was still the head of BNB, a manufacturer of complicated movements with a workforce of 180. Then came the financial crisis. Customers were no longer supplying the cashflow and he had to file for bankruptcy. Jean-Claude Biver, the head of Hublot, then BNB’s main customer, who before the bankruptcy had already bought up the stocks of movements and patents and recruited 30 of the watchmakers, took Mathias Buttet on board, along with the machinery plus leases and 28 additional specialists representing a dozen different trades. It was thanks to this crucial contribution that Hublot was rapidly able to lay the foundations for its own movement manufacture.

When Buttet spoke to Biver about his project and told him of the incredible Antikythera mechanism, which turned the history of science and technology completely upside down, his boss was enthusiastic: “We’ll do it!”. “Let’s do it!” Which is how Hublot, having recruited Yanis Bitsakis thanks to Buttet, by now a close friend, got involved in the story of the Antikythera mechanism in a very concrete way.

The mechanism

“The Antikythera mechanism is unique,” says an effusive Mathias Buttet. “It’s humanity’s first astronomic calculator, incredibly accurate. We’re now sure that it was designed and built during the second century BC, between 150 BC and 100 BC, maybe even a little earlier. The sum of astronomical knowledge, mathematical calculations and manual know-how that were needed to create it is mind-blowing. Just imagine, this veritable mechanical computer from a pre-computer age is capable of indicating multiple astronomical cycles, predicting eclipses and stellar events, the phases of the moon, the heliacal rising and setting of certain constellations, the course of the seasons, and the cycle of the Panhellenic Games of ancient Greece (including the famous Olympic Games).”

Around the size of a shoebox – a wooden box that its wooden casing has almost entirely disappeared – its bronze gears and cogs are driven by a crank on the side. It has two faces. One features a solar calendar displaying the day of the year, a two-coloured sphere showing the phases of the moon, a static display of the twelve signs of the zodiac and a circular scale for the 365 days of the year of the Egyptian calendar divided into 12 months of 30 days – that is, 360 days plus five additional days called “epagomenal days”, considered to be the days when the great Egyptian gods were born. The scale is moveable to allow an extra day to be added every four years, our leap years.

On the other side, on two large spiral dials, are a “Metonic” (after the Greek astronomer Meton) lunisolar calendar covering a cycle of 19 years, or 235 lunar months, and a Callippic calendar (after the Greek astronomer Callippus), which runs over 76 years, equal to 940 lunar months or four times the Metonic cycle. It also features the exeligmos cycle, equal to three saros cycles, or 54 years, which made it possible to indicate the precise recurrence of the solar and lunar eclipses. Lastly, a small calendar divided into four displays the towns and dates of the Panhellenic Games.

-

- Reconstruction of face A of the Antikythera mechanism

Mathias Buttet: “None of our so-called precision moon-phase watches achieves that kind of result. It’s just stunning. No fewer than 69 bronze gears dovetail exactly, the teeth of the different wheels are exceptionally fine, as little as 1 mm thick, and you find types of gear the existence of which we’d forgotten and which the archaeologists have revealed to us, such as these circular gears with non-linear cycles that let you change ratio in the middle of a stroke. Another extraordinary fact is that today we’ve succeeded in reading some 12,000 incredibly finely engraved characters: it’s the instruction manual for the Antikythera mechanism, which is literally written on it. The designers were trying to combine different bodies of knowledge, to explain operations so the indications could be read correctly and the numbers used properly. And we still don’t know everything about the Antikythera mechanism.”

The Antikythera watch

In 2012, in conjunction with the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, Hublot presented its tribute to the Antikythera mechanism. This is a reproduction of the mechanism, miniaturised to the scale of a watch. On one side is the calendar of the Panhellenic Games, the Egyptian calendar, the position of the sun and the movement and phases of the moon in the constellations. On the other side figure the astronomical lunisolar cycles: the Callippic, Metonic, saros and exeligmos cycles.

-

- The Antikythera by Hublot, introduced in 2012. Two identical copies exist, one of which is displayed at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, side by side with the fragments of the Antikythera mechanism, and the other at the Musée des Arts et Métiers industrial design museum in Paris.

The only concessions to modern time-telling are the hours and minutes display (a division unknown in ancient times) and, instead of a crank, a tourbillon escapement with a power reserve of five days.

The adventure is not over yet

But Hublot’s Antikythera adventure does not stop with this unique creation. Far from it. Now a stakeholder in the still ongoing official excavations (will we one day find the mechanism’s missing parts?), Hublot has placed its R&D department at the disposal of researchers. Mathias Buttet, who participates in every annual excavation campaign in the waters off the small island of Antikythera, is more than a little proud to explain what the two underwater drones in the process of being assembled are doing in his laboratory.

“The ship sank around 60BC and since then a thick layer of sediment has built up over it. What’s more, in around 400 AD, the island was struck by a huge earthquake. There was a tsunami and whole parts of the cliff overhanging the location collapsed. We developed balloons that would raise the rocks at a depth of 70 metres. There are more than 10 tonnes of rocks to move. One notable find made possible by this method was the gigantic head of a monumental statue of Neptune, which can be seen – still decapitated – in the museum in Athens. And we developed these underwater exploration drones.”

-

- Moving collapsed rocks with the help of balloons

Equipped with two slightly squinting cameras supplying impressive, high-resolution 3D images, the drones are fitted with a sophisticated metal detector. A Karcher-like jet nozzle cleans and carves away the sediment, which is sucked up by a pump into bags, which are then brought up to the surface, clearing the zone.

At the same time, the sediment is immediately analysed inside the drone by voltammetry, which determines the nature of the oxides it contains to an accuracy of 2ppm (two particles per million) – and, therefore, the nature of the object that may be buried there. “As you can imagine, over more than 2,000 years everything ferrous, including the outer lining of the ship, has dissolved into the surrounding area. The detector beeps all the time, but the drone’s analytical instruments enable us to refine the analyses by identifying concentrations of bronze, for example, or copper, lead and even gold and other metals,” Mathias Buttet explains.

-

- An underwater drone and its “mother”, designed and built in Hublot’s R&D laboratory

Many questions remain open. “This Antikythera mechanism is the only one in the world, but was it at the time?” he wonders. "Solving the equation of these gears and their ratios is a highly advanced mathematical operation, which calls for differential calculus. And why miniaturise the construction to that extent? Why make it transportable? Considerable effort has been put into it. Who financed it? Whoever designed it made a machine capable of predicting eclipses, in other words, the future… There’s magic in that, enough to bestow huge prestige… And with these explanations engraved on the machine itself, there’s also a desire to transmit knowledge…”

You sense a man enthralled by all these questions and in awe of the degree of knowledge possessed in ancient times. And when you see the mysterious object he himself is in the process of designing, it’s worth betting that the enthrallment is not about to end. “I fell in love with Antikythera and I’m determined to go on learning about this fascinating machine and its history.”

-

- Cinema and the Antikythera mechanism, here reimagined as the Dial of Destiny, a time machine, in the recent Indiana Jones V film.