The National Museum of Science and Technology in Milan is known around the world for its reduced scale models of Leonardo De Vinci’s great inventions, and hence the name of this prestigious museum dedicated to the applied and industrial arts.

Unfortunately, for a number of years now, the room housing timekeepers has been in a state of disrepair, leaving unavailable many wonderful pieces that would make other ‘time’ museums around the world green with envy. Obviously, there is hardly any point in saying that the renovation and reopening of this ‘timely space’ is indeed a happy event.

This great undertaking required the entire re-structuring of the exhibition space, the creation of a new catalogue listing the museum’s nearly 2000 objects, and an in-depth study of a cultural journey through 500 years of timekeeping history. The endeavour was made possible thanks to the help of Wyler Vetta. The Italian watch brand, among others, whose products are made in Switzerland, also contributed to the exhibits in the museum with its anti-shock ‘Incaflex’ device that has increased the reliability of watches since its introduction in the 1930s.

Wyler Vetta’s sponsoring activities in the timekeeping domain are in line with its earlier activities. It is a member of the Binda Group, a watch production and distribution company based in Milan, and was founded around 1930 by Innocente Binda. Binda, himself, was instrumental in getting the first room dedicated to timekeepers established in Milan’s Leonardo Da Vinci Museum of Science and Technology. The inauguration of this first space took place in 1959, with the aid of donations from the Pinardi and Parisi collections. Others were quickly added, among them the notable reconstruction of the original workshop belonging to the famous 17th century watchmaker Bartolomeo Antonio Bertolla, from the Trente region. Not only were his original drawings, tools, machines and workbenches conserved but also the magnificent ceiling that was carefully taken apart and rebuilt inside the museum. Probably the most important piece is the reconstruction of the Astrario by Giovanni Dondi, carried out by Luigi Pippa in 1963 based on a manuscript preserved in the Episcopal Capitulary Library in Padova. The original Astrario was made during the middle of the 14th century and later destroyed. Representing one of the summits of time measurement during the Middle Ages, it appears as a tower sitting on a base of seven columns forming a château. Inside the base is a complex motor that is activated with a counterweight on a cord, while the château’s seven faces display the movements of the sun, moon, and the five planets known at the time (Venus, Mercury, Mars, Saturn and Jupiter). The clock has no hands, but indications are read from the rotations of the faces. Below the sun ‘dial’ is a real clock face, divided into 24 hours and in fractions of ten minutes. On the opposite side, is a face showing the eclipses of the moon, while on the upper part of the base is the calendar wheel, which makes one rotation each year, showing the times of sunrise and sunset each day at Padova’s latitude, as well as the days of the week, the names of the saints and the dates of fixed holidays. It is interesting to mention in passing that the faces of the sun, moon and planets are in line with the astronomical principles of Ptolemy that placed the immovable Earth at the centre of the universe.

For those interested in the history of horology, the reopening of this space is indeed a happy and timely event for Milan and for the rest of the world.

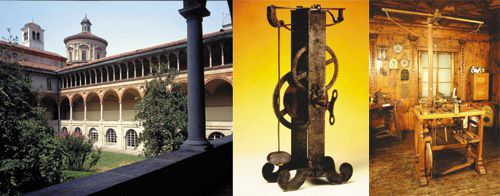

The cloisters of the National Museum of Science and Technology “Leonardo Da Vinci”, Milan.

The reconstruction of a mechanism imagined by Galileo Galilei.

The boutique of Bertolla, XVIIIth century.

The reconstruction of the Astrario of Giovanni Dondi, 1963, after a XIVth century manuscript.

The Nocturne clock by Treffler, 1660.