The Annual Calendar, the first useful complication

Patek Philippe launched its patented Annual Calendar in 1996. It is said to be ‘useful’ because it is practical, easy to use, and very readable. The Annual Calendar was, in fact, the first wristwatch to automatically display the month, day and date for all the months of the year that had 30 and 31 days. The only exception was February, of course, which required one correction per year.

To make this timepiece, the watchmakers at Patek Philippe replaced the usual cams and levers by gear trains. As a result, the Annual Calendar has more component parts (330) than the brand’s Perpetual Calendar that comes with lunar phases (275 parts). Although its design is very sophisticated, its rationalized architecture makes the piece less complex to assemble.

The flagship of the family of ‘useful’ complications, the Annual Calendar, named Watch of the Year in 1996, enjoyed very rapid success, so much so that even women were wearing the 37 mm diameter timepiece, although it was originally intended for men. Its ease in use, its ingenuity, and its classic appearance all contributed to the high degree of acceptance by the public.

In 1998, Patek Philippe added a power reserve indicator and a high precision lunar phase display to the Annual Calendar. The moon phase display is so accurate that it is off by only one day every 122 years.

The new feminine face of the Annual Calendar

Because of the growing interest by women for mechanical watches, Patek Philippe is today presenting new and purely feminine variations of its Annual Calendar. Maintaining its original 37 mm case size, the ladies’ version features a greatly refined dial. But, “in the same manner as a couturier would reinterpret a tuxedo for a woman,” the lines have remained nearly identical. The mother-of-pearl dial and diamonds give a very chic touch to a watch that still remains very much a Patek at heart.

The feminine version of the Annual Calendar is quite attractive with its yellow or white gold case, its bezel set with 156 round diamonds offset on two unequal rows, its natural white or Tahitian black mother-of-pearl dial with the applied Roman numerals and golden ‘leaf’ hands, and its alligator bracelet available in mat champagne or brilliant grey colours. The lunar phases are displayed at 6 o’clock, above the date. The caseback is also made of sapphire crystal.

An enlarged men’s version

In the new men’s version, the Annual Calendar has taken on some muscle, but without exaggeration. The case has gone from 37 mm to 39 mm in diameter. This is enough to give it a more affirmed character while offering improved readability for the dial indications, namely the auxiliary dials for days, months, date, power reserve and lunar phases. The case has been refined and features yellow or white gold, with a lacquered cream or slate grey dial in a sun pattern, protected by a sapphire crystal. The Roman numerals have been replaced by three Arabic numbers. The brown alligator strap has a new fold-over clasp whose design is similar to the traditional Patek Philippe buckle.

The special limited edition ‘Patek Philippe Advanced Research’ timekeeper

This new 39 mm Annual Calendar has been selected to house, for the first time in watchmaking history, an anchor escapement wheel made of silicon.

The owner of one of these 100 watches will be able to observe this special anchor wheel through the sapphire crystal caseback that comes equipped with a special loupe. A bridge has been intentionally displaced in order to better see the wheel, which stands out from the other component parts by its anthracite grey colour with violet overtones, a characteristic of silicon.

Contrary to Patek Philippe’s usual tradition of not placing any inscriptions on the back of its watches, the term ‘Patek Philippe Advanced Research’ has been specially engraved on the sapphire caseback of this remarkable watch. This is doubly justified because this watch incorporates another technical innovation, namely that the 21 carat gold oscillating weight has been mounted on zirconium ball bearings, also for the first time in watchmaking history.

Why a silicon wheel?

We must remember that Patek Philippe, besides its important efforts in safeguarding and maintaining traditional techniques and crafts in the art of watchmaking, has also been in the forefront of inno-vative advances to improve this same art as it moves into the future. This work has resulted in the brand applying for more than 70 patents, of which about twenty have indeed transformed the course of watchmaking.

For more than fifteen years, Patek Philippe has been interested in a particular domain: the development of new materials that don’t need lubrication. (Since lubrication has to be carried out regularly, it is one of the recurring problems in the servicing of watches.)

In this regard, the brand’s recently created ‘New Technologies’ department has established partnerships with various reputed research centres such as the Federal Polytechnical School in Lausanne, the Institute for Microtechnics at the University of Neuchâtel, the Swiss Centre for Electronics and Microtechnics, and the COMLAB Laboratory. These five would like to “reinvent the wheel” so to speak.

Extraordinary physical properties

The physical properties of silicon, or more precisely monocrystalline silicon whose structure is identical to a diamond, is the ideal candidate for use in micro-mechanics, and especially in watchmaking. Monocrystalline silicon is not magnetic, is extremely hard (1100 Vickers compared to 700 Vickers for steel), and is highly resistant to corrosion. Finally, despite its hardness, the microstructure of silicon remains flexible.

In a traditional watch with an anchor escapement, 65% of the energy of the movement is used by the escapement mech-anism. The mass of the wheel therefore has a crucial influence. Because of its lightness, having the anchor wheel in silicon improves the transmission of energy to the balance. And, even better still, thanks to its hardness, perfectly smooth surface, density, and its excellent coefficient of friction, there is no need to lubricate the silicon wheel.

A revolutionary process of fabrication

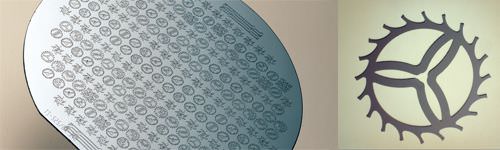

There is also another fascinating aspect, which is that the fabrication process has strictly nothing to do with traditional methods, which involve machining, drilling, etc., because this type of wheel is nearly entirely made by ‘photographic’ means.

An image of the piece to be produced is projected onto a round silicon wafer measuring 100 mm in diameter by 0.5 mm in thickness. Using this size, about 250 wheels can be made. The wafer is composed of three different substrates or layers of silicon, with the central substrate being the separation layer. After the ‘photo’ is developed, the exposed lacquered substrate is cleaned away, leaving the non-exposed parts on the wafer. Then, the non-exposed lacquered substrate is etched with plasma down to the separation layer. The silicon wheels are then released by isotropic etching. The pieces that come out of this operation have only to be cleaned on the surface and they are ready to go. They are all identical and usable as they are, without needing balancing, centring or polishing.

Now, the wheel producing process has gone from 30 different steps to just one, from the loud noise of mechanical equipment to the white clean chambers of high-tech laboratories.

The future in the spirit of tradition

Patek Philippe is certain that this innovation is “an important step into the future of mechanical timekeeping” and a good indication of its future developments. The primary objective, however, still remains the improvement of a watch’s operation over the long term.

In all of this advanced research, the most emblematic example of the “Patek Philippe spirit” is that this 21st century style of watchmaking lends itself perfectly to the very severe quality and operational criteria of the Poinçon de Genève or Geneva Seal, to which all the brand’s watches are subjected.

In their wisdom, the watchmakers, who wrote about the anchor wheel, decreed that it “must be lightweight with a thickness not greater than 0.16 mm for large pieces and 0.13 mm for pieces less than 18 mm in diameter, and the locking-face must be polished.”

With its minimal density and the perfection of its ‘naturally’ polished surfaces, Patek’s hi-tech anchor wheel satisfies all the traditional criteria and in fact, even greatly exceeds them. There can be no doubt that, with the string of innovations to come along in the future, these criteria will also evolve as they have done several times already. These evolutions will certainly make way for continual improvements in the art – and science – of timekeeping.

Source: April-May 2005 Issue

More...Click here to subscribe to Europa Star Magazine current issue.