ans Christian Andersen visited the site in 1836: “Presently we find ourselves in an underground watermill. No-one above the surface imagines the torrent that roars beneath their feet. Water falls several toises* onto rattling wheels which, as they turn, threaten to catch our clothes and have us turn with them. The steps we stand on are damp and worn. Water trickles from stone walls and, nearby, the chasm opens before us.”

The celebrated Danish author was visiting Le Locle as a guest of Jacques Frédéric Houriet, renowned as the “father of Swiss chronometry”. Houriet’s daughter had married another great watchmaker, Urban Jürgensen, a fellow Dane who, we can imagine, would have taken Andersen to visit the underground mill. After all, the difference between a tiny clockwork mechanism imprisoned in a case and the impressive hydraulic machinery in its cave is simply a matter of scale. Both are centred around gears, mechanical transmissions and a regulated power supply.

-

- Through gears and an axle, the wheels that turn vertically underground horizontally rotate the millstones above them, at the entrance to the caves, as this nineteenth-century engraving shows.

In the first century CE, the Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius was first to set out the functioning of a watermill in scientific terms. In book number ten of his treatise De architectura, he describes water wheels, water mills and water organs, an early example of “mechanical art”, while book number nine cites Ctesibius who “devised methods of raising water, automatic contrivances and amusing things of many kinds, including the construction of water clocks.”

The relationship between, or simultaneity of, machines that grind grain, machines that count time and machines that produce music is clear.

Three centuries of history

The saga of the Col-des-Roches underground mill began in 1651 and ended when the site was shut down in 1966. Over the course of its three-hundred-year existence, the mill lived many lives, under many owners and in many guises, from a flourmill operated by millers and bakers to a sawmill and, finally, an abattoir.

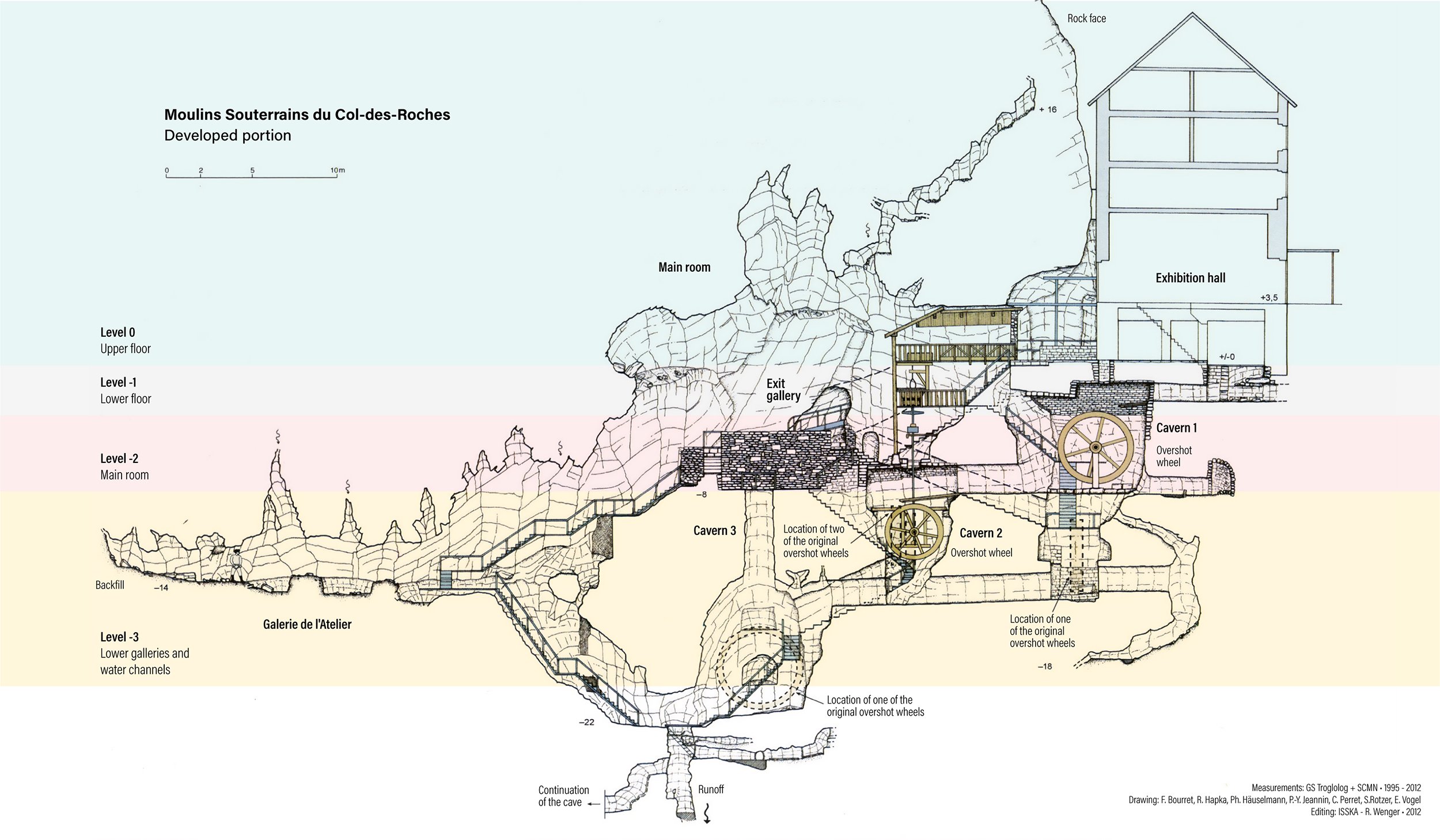

This subterranean exploit took seed in 1660 when a certain Jonas Sandoz, an influential figure with political connections and the new owner of the concession, undertook major construction work. The river that powered the mill emptied into a natural cavity, where it disappeared into an abime, which Sandoz had excavated. “There are two artificial caves in addition to the natural cave. They are connected by channels which carried the water that turned the wheels Sandoz had had built. Construction work extended to inspection galleries and steps were cut into the rock to give access to the lower levels. In total, five wheels turned simultaneously and transmitted energy through vertical axles to the mill itself,” explained Caroline Calame, curator at the Fondation des Moulins Souterrains du Col-des-Roches and our guide through the dark and dank passages where, having descended narrow stone steps, we came face to face with the gigantic wheels in their rocky home.

“Terror and admiration”

My mind played tricks and, for a moment, I could see the wheels turning, hear the gush of water pouring over them, the creak and groan of the wood and metal structures as they meshed. Nor was I alone: visitors in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries would emerge with tales of the millers in their white smocks, dusted with flour, moving around like ghosts.

Among the many who travelled from far and wide to see the mill was Francisco de Miranda, who fought alongside Simón Bolívar for Venezuela’s independence from Spain. After his visit in 1778, he wrote how “I had to become quite soaked in order to view everything inside.”

Later, in 1838, a certain Frédéric Caumont described “the roar of the water that descends through three falls to great depth, the endless beating of the clappers, the light from our lanterns dancing over the sombre rock faces, the ghostly figures of the millers, dusted in flour from head to toe: all of this cast a strange and wonderful impression. We were seized by an indefinable mix of terror, astonishment and admiration (…).”

Imagine a watchmaker on his way home from nearby Le Locle, having delivered his latest production, who decides that he too will risk getting soaked and descend into the earth to see for himself the extraordinary wheels he has heard so much about.

Inevitably he will think of the wheels that he cuts, hammers and polishes in his farmhouse; so very much smaller yet identical in so many ways. He’ll think of the forces at work – and note how the water that drops into the wheels’ buckets lacks the regularity of his springs – and the calculations that had to be made. He’ll admire the gears that transmit the vertical force to the mill above and the materials used. He’ll marvel at the ingenuity of the structure and recognise the quality and skill of the artisans who built it, applying the same science of mechanics that he employs — albeit with less finishing and decoration.

The wheel turns

That we can visit Moulins Souterrains du Col-des-Roches, and experience some of the same emotions as our eighteenth-century watchmaker, is thanks to a decades-long restoration and reconstruction project. Left derelict after the last occupants, who had opened a “border abattoir” (France is on the other side of a tunnel through the rock), the caves were filled with rubble and pieces of animal carcass… at the risk of polluting the water that flows naturally underground. They were rediscovered in 1973, full of mud and emptied of the wheels, mechanisms and millstones.

It took fifteen years to clear the channels, passageways and steps cut into the rock. A mechanism from a nineteenth-century mill was installed in the main cave then another waterwheel was built and placed in the second. Finally, in 1987, the mill opened to the public. Since then, an overshot wheel has been installed in the first cave and the hydraulic circuit brought back into service. Above ground, the buildings have been restored and now house the collections of the Le Locle history museum. Today the mill stands as a spectacular, yet also intimate, reminder of the lives and engineering skills of our forebears.