word of Latin origin, fair harks back to religious practices or pilgrimages. Once assembled, the participants, who had come from far and wide, began to trade, sometimes to acquire commodities that were unknown to them, and sometimes simply for their own subsistence during their stay. Today, only the commercial transactions remain.

Whereas markets are traditionally designed to sell artisanal products and local foodstuffs, the first fairs, which date back to antiquity, offered wholesale merchandise to merchants who came to stock up on goods so as to resell them.

With the Crusades, travel by land, river and sea routes increased. Medieval trade took advantage of developments such as the shoeing, harnessing and teaming of horses, as well as iron rings inside the wheels of carts and wagons, and the improvement of roads. Brotherhoods of a religious nature flourished during the Carolingian period.

As time went on, artisans from the haberdashery, goldsmith, silversmith and drapery trades formed guilds that were tasked with defending the interests of their members. For their part, merchants formed guilds in order to protect themselves from banditry and excessive tolls. In the late Middle Ages, structured labour law was introduced in Italy, Flanders and Champagne.

At fairs, tradesmen were transformed into businessmen, who were able to deal with a high volume of transactions thanks to promissory notes, a means of payment that made it possible to honour a debt from afar by going through two bankers who communicated with each other. A form of capitalism thus emerged.

Swiss watchmaking joins European fairs and exhibitions

From the late 13th century, gold and silverware were presented at fairs in Geneva. The first watches made in Geneva in the 16th century were, for the most part, exported, given the lack of local prospects. Forced to leave their country out of economic necessity, the city’s merchants travelled to the lands of their ancestors, participated in the great European fairs of Reims, Troyes, Cologne and Leipzig, and also visited eastern capitals such as Constantinople from 1592 onwards.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Swiss watchmaking towns were a dependency of Geneva, before freeing themselves from the city’s tutelage. As of the 18th century, they exported their products autonomously, via fairs in Leipzig, which was the most important, Frankfurt, and Augsburg, a gateway to the Central European market.

Exhibitions were not an extension of traditional fairs, but rather the continuation of events organised in France and England in the 18th century by Academies and Societies of Fine Arts in order to present the latest artistic creations to the public.

The importance of national and regional events

In 1804, the first Exhibition of Fine Arts and Industry took place in Bern. This unusual name can be explained by all the different kinds of expertise necessary at the time to transform materials. This first modern exhibition was followed by others in 1810, 1818, 1824 and 1830, all of which were held in Bern. Beyond its commercial objective, it allowed the country to showcase its dynamism and promote its values of technological progress, work, competition and the development of a collective identity.

In 1843, the National Artisanal and Industrial Exhibition in St. Gallen brought together two different approaches to production, while the exhibitions in Bern in 1848 and 1857 took place under the banner of Swiss industrial exhibitions. The regional events of the 19th century benefited from the work of industrial associations. As a result, regular events in Geneva specialised in watchmaking and jewellery, as did an 1881 exhibition in Neuchâtel. An exhibition in Appenzell in 1881 focused on embroidery. The 1863 Neuchâtel Watchmaking Exhibition coincided with the Swiss Shooting Festival, and a mechanics section was added in 1879. From then on, specialisation became more pronounced, with an event held in La Chaux-de-Fonds entitled the National Watchmaking Exhibition and International Exhibition of Machines and Tools Used in Watchmaking, as well as the International Exhibition of Watchmaking, Jewellery and Related Fields that took place in Geneva in 1888.

Global and industrial showcases

World’s Fairs emerged as of 1850. They were also called Universal Exhibitions as they dealt with every aspect of industry. Initiated during the Industrial Revolution, these fairs served cultural (educational), political and economic purposes. The first world’s fair took place in London in 1851, and was followed by fairs in Paris (1855), Vienna, Philadelphia and Chicago. Among other things, these fairs consolidated the reputation Swiss watchmaking had acquired on the international market since the 18th century.

At the Melbourne (1880) and Chicago (1893) fairs, Genevan watchmakers insisted on presenting separately from other Swiss watchmakers in compliance with criteria that demonstrated their specificity. In Chicago, their catalogue championed the superiority of watches from Geneva and the excellence of its school for watchmaking and its observatory.

In line with the notion of universality promoted by the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris, Swiss watchmaking was presented in five sections: group exhibitions of Genevan watchmaking; manufacturers from Fleurier; manufacturers from Le Locle; mechanics specialists from Couvet, and manufacturers from La Chaux-de-Fonds.

The first Basel Fair (1917)

Nevertheless, after 1900 enthusiasm for progress and industry started to wane. The nature of world’s fairs had to change. The first Swiss Design Fair Basel took place on 15 April 1917, with 831 companies from all sectors of the Swiss economy and a section devoted to watchmaking and jewellery. The event continued to develop over the following decades. In 1942 Geneva celebrated its bimillennial. On this occasion, manufacturers, journalists and historians from the world of watchmaking came together to organise an exhibition of Genevan production.

Intended as a one-off, the Geneva Watches & Jewellery Fair was such a success that it continued for forty years. From 1942 to 1982 the event took place at the city’s museums and hotels celebrating both the old and the new. In 1961, the Musée Rath called it the “most important watchmaking and jewellery event”, to the extent that it was hosted by Goldsmith’s Hall in London and the Hotel Bayerischer Hof in Munich in 1975 and 1977 respectively.

From fair to exhibition

From 1921, watchmaking, together with other disciplines, was part of the Swiss Design Fair Basel. In 1931 the first Swiss Watch Fair was held. It had its own pavilion. It became the European Watch and Jewellery Show in 1973 and was renamed Basel ten years later. In 2003 it took on the name of Baselworld Watch and Jewellery Show.

In 1991 the Salon International de la Haute Horlogerie made its début at the Palexpo in Geneva. It was a private event that brought together the watchmaking brands of a large international group, in compliance with the specific criteria of the luxury industry.

As professional events designed for professionals, the two exhibitions share the same objectives and definitions as the earliest fairs. But the education of the public and the transmission of values, so important in the 19th century, no longer have a place.

QUIZ

What was the “Basel Fair”

like in 1970?

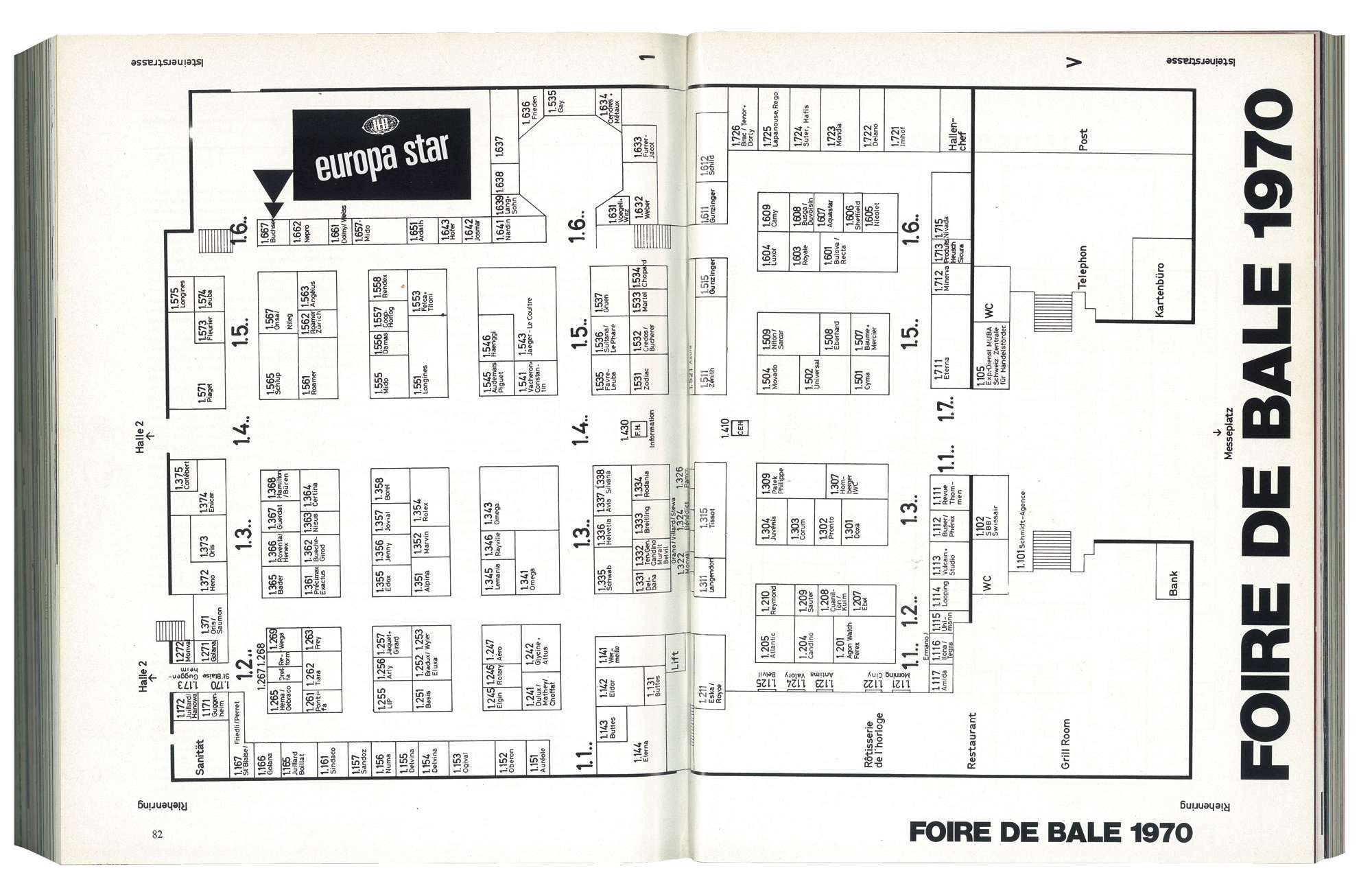

The floorplan of what was still called the “Basel Fair” 47

years ago, taken from our Europa Star archives, shows

some similarities and some major differences.

How many brands are still present today?

How many have disappeared off the face of the earth?

How big were the booths, and where were they located?

Is it possible to infer some sort of hierarchy?

Take a few minutes to have a good look at it. You’ll find it

very interesting, and probably quite surprising too!