t Cernier, the elegant architecture of Décors Guillochés blends beautifully into the countryside of Val-de-Ruz, the result of a certain aesthetic approach reinforced by a heightened awareness of the environmental issues at stake. “The 120m² of solar panels and the green roof cover 85% of our power requirement,” explains Yann von Kaenel, the director of this independent enterprise specialising in engine-turning.

For us, the proprietor retraces his atypical career: “After eight years of applied research at EPFL and in Canada and four years with a spin-off from CSEM, I craved independence; I didn’t want to be a link in an opaque hierarchical chain any more.”This doctor of Technical Science (he did his PhD on the properties of thin layers of synthetic diamond) and experienced engine-turner, or guillocheur, works behind the scenes in a currently burgeoning craft.

-

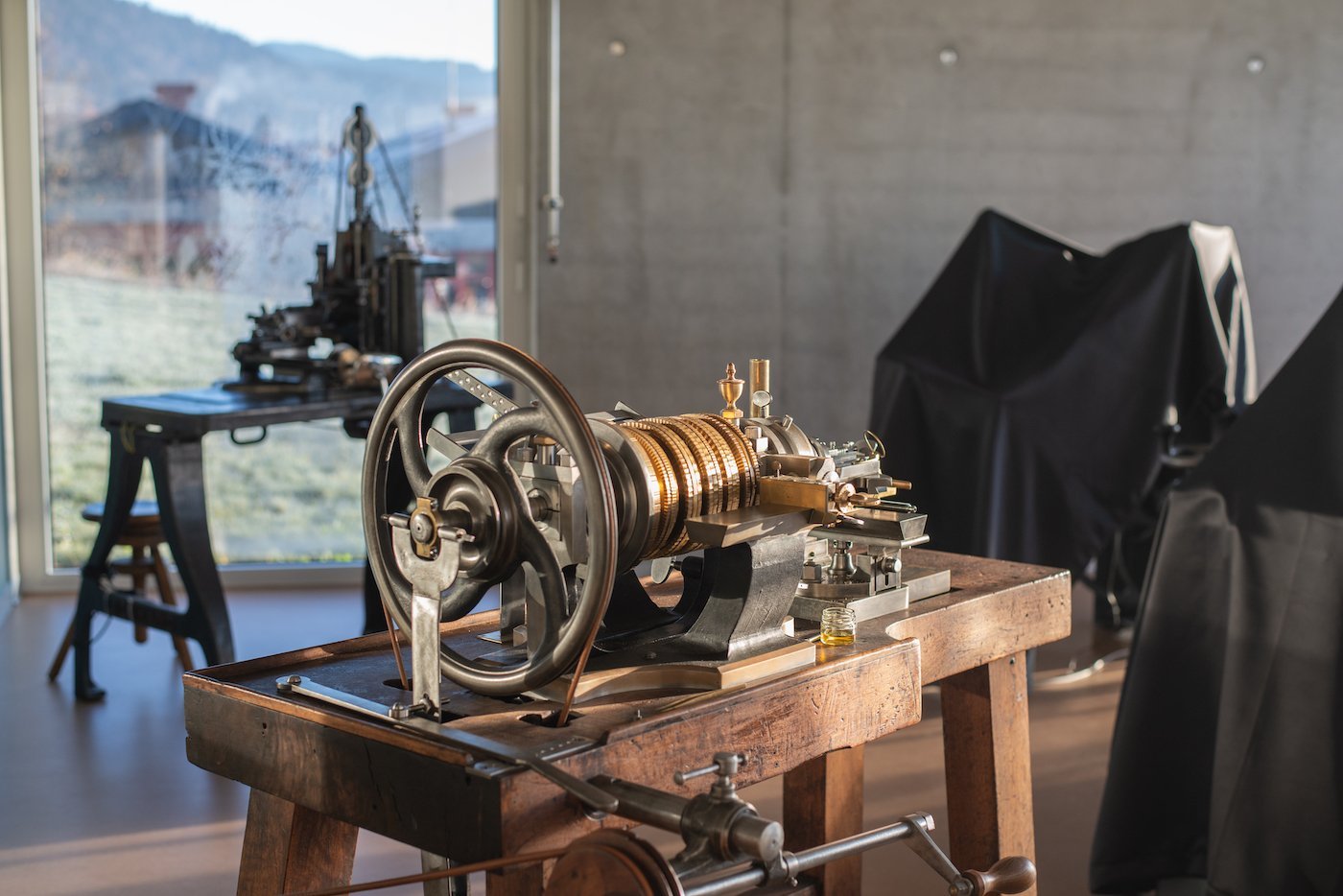

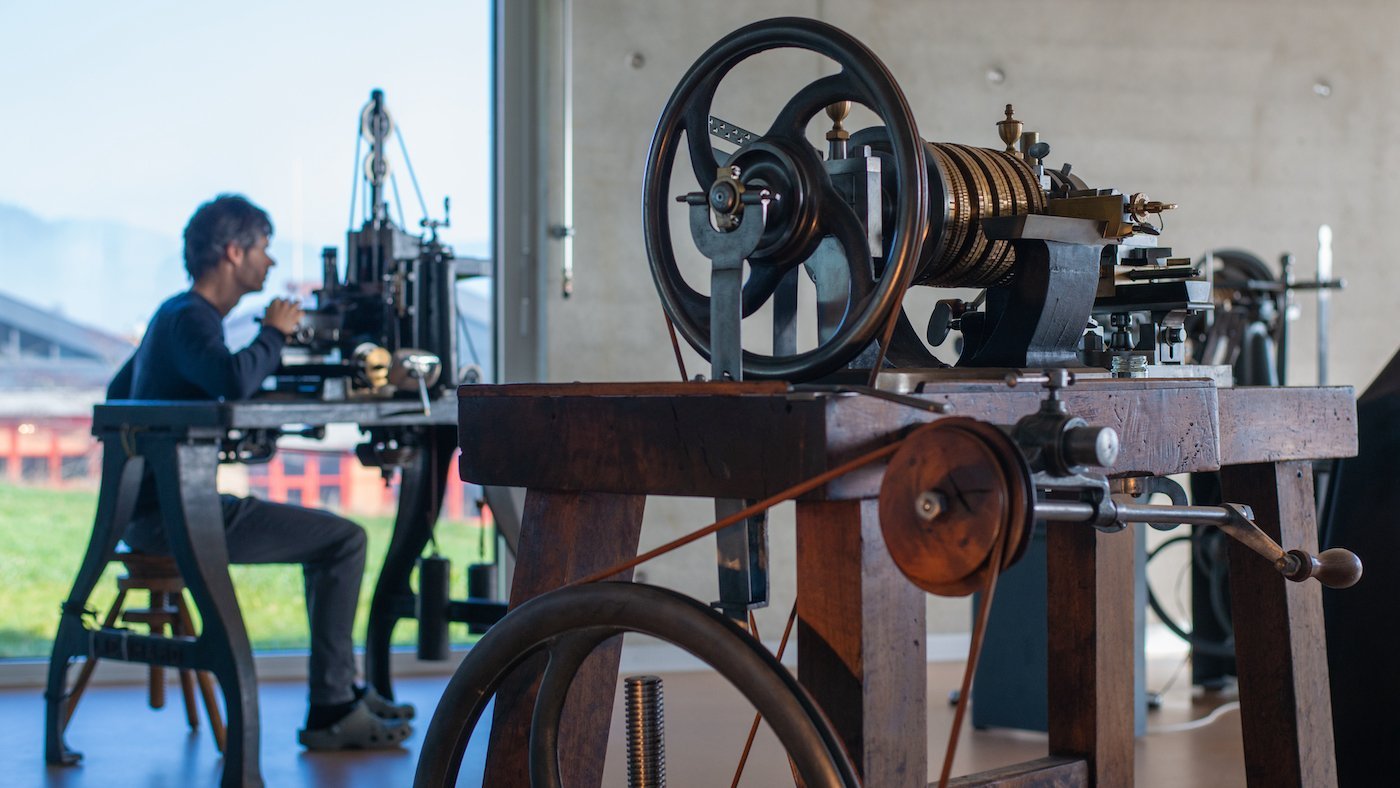

- Yann von Kaenel between a traditional rose engine (foreground) and a straight-line engine

In 2005, after two whole years spent learning the art of guilloché – from adjusting the lathe and creating pattern right through to the production of steel dies – Yann von Kaenel took over as director of the company he founded with his father, René (see sidebar). Today, Décors Guillochés employs a workforce of some ten people and in 2022 produced around 4,000 dials.

-

- At Cernier, the elegant architecture of Décors Guillochés blends beautifully into the countryside of Val-de-Ruz.

Despite several successive economic crises, “no employee left the company by choice,” the artisan points out, adding that they “attract unusual profiles, from horticulturalists to dental technicians, including one chef with a passion for reduced-model boats. The only thing everyone has to have in common is a diehard passion and an unflagging attention capacity.”

The Breguet legacy

Like engraving, the art of guilloché consists of removing material and creating repetitive, regular grooves on a metal support. The objective is to create complex patterns, the visual harmony of which is reinforced by a clever play of light and shade.

As so often in the decorative arts, its origin lies somewhere between France (in the 15th century, a certain Guillot is said to have engraved ivory, wood and horn) and Italy (the verbs guiocciare and guttiare are more evocative of an engraved motif in the shape of a droplet).

-

- An advertisement by the manufacturer of “guilloché machines” – rose engines – Lienhard & Cie of La Chaux-de-Fonds, published in the Indicateur Davoine directory of 1923

- ©Municipal library of La Chaux-de-Fonds

The invention of guilloché on dials is, however, unanimously attributed to Abraham-Louis Breguet. He created a comprehensive repertoire of universally recognisable patterns, including Clou de Paris or hobnail, the toothed crémaillère motif, flinqué, barleycorn, grain de riz (“grain of rice”) and basket weave.

-

- “Inca Sun”” guilloché pattern, an example of Yann von Kaenel’s creativity The tenacity of the manual engine-turner

The tenacity of the manual engine-turner

Guilloché machines are large tools and complex to use. Traditionally placed horizontally on a wooden table similar to a watchmaker’s bench, the lathe consists of a large metal cylinder (the spindle) on which is mounted a set of stacked cams, also called rosettes – hence the English term for these machines: rose engine.

With his left hand the cutter turns a handle which slowly – via a belt – drives the spindle. With his right hand, he brings a burin, affixed to a carriage, close to the dial he wants to engrave. Once a circular line has been engraved, the cutter displaces the burin slightly and repeats the operation. “Some patterns require a thousand lines,” says Yann von Kaenel. “You have to stay focused from first to last. You can’t let your attention wander!”

The second type of traditional rose engine – the straight-line engine – is more compact, but works in exactly the same way. They are easier to find today, for reasons of space. And as the name suggests, straight-line engines produce mostly rectilinear patterns.

From shade to light

Rather like enamelling, guilloché also fell out of fashion for a long period. Even back in June 1924, the watchmaker Charles Piguet-Fages lamented the closure of the guilloché class at the Technicum school of La Chaux-de-Fonds, “too many workers in this speciality remaining unemployed to undertake the training of new apprentices”.

“Nevertheless,” he goes on, “although lengthy training is necessary to make a good guillocheur, we believe that elements of this speciality should be taught to engraving apprentices.” Training in guilloché would gradually disappear in favour of engraving. For decades, the lack of interest in this decorative craft led to a marked decline.

-

- Traditional grain de riz guilloché pattern

Then, contrary to all expectations, affection for it blossomed anew and “the major brands are coming back”, as the head of Décors Guillochés confirms. The watchmaking ecosystem is rediscovering this craft. In Val-de-Travers, for example, the independent watchmaker Kari Voutilainen launched an ambitious project for a guilloché training school, engaging George Brodbeck – the 2023 laureate of the Prix Gaia – and, in the nick of time, safeguarding the existence of several traditional rose engines.

Between CNC and hand-guilloché

At Décors Guillochés, customers also find a heritage of inestimable value made up of several hundred patterns. The legacy of decades of work by René Von Kaenel (see sidebar), others have been developed by his son Yann. “During slack periods we create new ones,” Yann explains. “To date, I’ve listed 580 patterns. They’re classed by type and by how they’re constructed. On a guilloché machine, the way you align the passes or how you space them allows for infinite combinations: you can go on creating for generations.”

Some purists think that the art of traditional guilloché should be done by hand. Yann von Kaenel takes a far more pragmatic attitude and is always developing new methods. Because guilloché has been in a constant process of adaptation for decades.

-

- Patent for a Lienhard & Cie rose engine

Back in the early 20th century, the manufacturer Lienhard innovated with the introduction of a machine that did guilloché by copying, a method that Roland Tille, the creative director of dial-maker Stern Frères in the 1970s, would call “tapestry” guilloché. Incidentally, Audemars Piguet has used this technology since the introduction of its Royal Oak model in 1972.

The other possibility consists of stamping the dial with a stamping press and a die bearing the guilloché pattern in negative, ideally in steel. This is the procedure used today to create the motif on the Patek Philippe Nautilus model.

Lastly, a guilloché pattern can be engraved on a dial with the help of a CNC machine. To programme the machine requires all the experience and competence of a trained engine-turner and is by no means a taboo for Yann von Kaenel. “Even though hand-guilloché has been very much in demand for several years now, our business consists of CNC and manual work in equal parts.”

Proof once again that tradition and modernity can coexist in perfect harmony.

René von Kaenel, a repository of know-how for the next generation

Europa Star: You are the son of the engine-turner René Von Kaenel, the name behind RVK Guillochage, now known as Metalem. Can you tell us about his professional career?

Yann von Kaenel: My father, a trained stamp-maker, joined forces with two hand-engravers to form the company L’Eplattenier, Blandenier et Cie. When one of his guilloche clients in Neuchâtel – a Mr Béguelin – retired, he bought several of his rose engines. At the height of the quartz crisis, he began to teach himself the art of guilloché in 1978.

For twenty years, in response to strong demand, my father’s workshop was the only one to train and employ future engine-turners. It became the go-to company for numerous dial-makers, including Stern Créations and Metalem, as well as several luxury watch brands the names of which I’m still not allowed to divulge. He also manufactured steel guilloché dies, an absolute rarity in the industry.

In 1996, when his two friends retired, my father joined forces with Metalem and renamed the company RVK Guillochage (the initials standing for René Von Kaenel). Two years later, he sold his shares in the company to Metalem and he still does engine-turning guilloché in his garage with the help of a former employee – the mother of Yann Tripet, the current director of RVK Guillochage.

The early 2000s saw a boom in guilloché. That was when I decided to join him, which led to the creation of Décors Guillochés SA.