lthough the watch industry continues to grow, some wonder if globalisation, computerisation and the internet will ultimately weaken it. However, the industry has weathered many technical and design crises over two centuries, each seemingly insurmountable. During every crisis lone innovators rose to challenge the status quo – ridiculed and rejected but ultimately embraced. Though it is often difficult to uncover their stories, why not cast a light on some of these unsung heroes of the industry?

Paul Perret was a serial disruptor. His balance spring and timing machines enabled mass production, he promoted patent protection (and was first in line to receive one), and he offered a solution when a cartel cornered the balance spring market. The industry responded with anger and ridicule, rejecting Perret as a charlatan and a fraud, and writing him out of history. Yet each of these moves ultimately proved correct and helped secure a future for the Swiss industry.

Disrupting the regulators

Watches were made mostly by hand before the 20th century, with each watch passing through numerous small workshops before it was ready to be sold. Each component came from a specialist, from the base ebauche to the wheels, springs, hands, and case. The watch would be roughly assembled, torn down and tuned, and reassembled before being handed over to a specialist for regulation. The skill of the regulator was so prized that competitions were held and prizes awarded in chronometry. Yet regulation was more art than science, with each imperfect spring coiled by hand and selected to cancel out the imperfections of the balance. It is no surprise that there were well over 60 such workshops in La Chaux-de-Fonds alone by 1880!

-

- Patent number 1

But the atelier of young Paul Perret stood out from the rest. Watches he regulated routinely earned certificates from the observatories in Geneva and Neuchâtel, yet he was also able to handle an incredible volume of orders. His high-profile workshop, directly in front of the railway station on the main boulevard, churned out an average of 300 regulated balances per day in the 1880s. Perret amazed his peers with his ability to regulate a balance in minutes rather than days using machines of his own creation, the “Campyloscope” and “Talantoscope”. Many, including the director of the Neuchâtel observatory, became admirers and friends of the quick-witted young man.

At the time, the only way for innovators like Perret to profit from their inventions was to keep them secret. Unlike France, England and the United States, Switzerland had no patent protection system, though the concept was rapidly gaining international acceptance. After the Swiss government rejected a patent law, Perret enthusiastically joined a referendum campaign in 1882. But voters rejected the idea, fearing that it would threaten the system of small-scale production. The same protectionist sentiment in La Chaux-de-Fonds delayed electrification and construction of larger factories there.

-

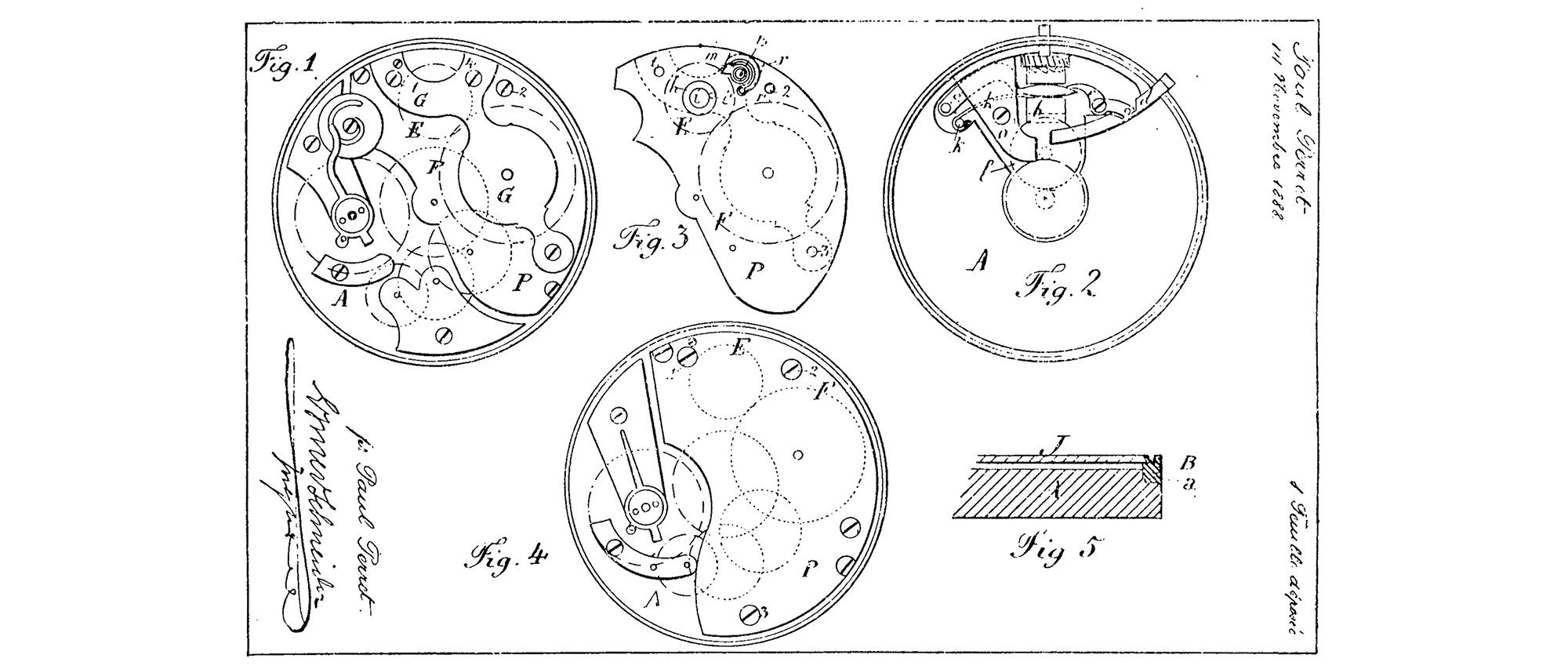

- Beautiful illustration of the Talantoscope from 1876 Journal Suisse d’Horlogerie (1876)

But the Industrial Revolution in England and the United States ultimately forced the Swiss to adapt. Towns like Saint-Imier, Bienne, Grenchen and Tavannes were willing to allow large factories if it brought industry and employment. And the enforcement of foreign patents in Switzerland put local inventors at a disadvantage. On June 29, 1888, Swiss law established a system of patents with a patent office opening on November 15 in Berne. Paul Perret was ecstatic, arriving the night before to ensure that he was first in line. He ultimately registered 5 of the 120 patent applications received on that first day!

On June 28, 1889, an anonymous account was published in newspapers in key cities and towns in the Swiss watchmaking regions. Calling Paul Perret “among the boldest innovators in this industry,” the letter said his secret invention would eliminate the time and skill required to regulate a watch balance and spring. It is natural to be suspicious of change, especially when it threatens the livelihood of individuals and upsets established practices. So it is no surprise that the Perret letter was met with uncharacteristic scorn and fury.

-

- Anonymous Perret Letter - The “bombshell” Perret letter L’Impartial (1889)

Some commentators angrily noted that the tests touted in the article had not been performed properly, while others worried that Perret would use his patent to withhold the invention in Switzerland, and give foreign competitors an advantage. But the most astonishing response was a satirical advertisement lampooning Perret and his inventions and asking a ridiculous licensing fee. Perret’s friends soon responded, taking responsibility for the original article and endorsing the capabilities of his invention, but the damage to his reputation was done.

-

- The satirical “Campi Loos” advertisement L’Impartial (1889)

Extraordinary progress! A young compatriot, having after eighty-five years of study achieved the goal of his research concerning a machine for the automatic adjustment of chronometers, recommends himself to the industrialists of La Chaux-de-Fonds and the surrounding area. With the aid of this machine, he can provide after 12 hours two gross adjusted chronometers with a first-class bulletin from the Observatory, observed in 36 positions, guaranteed to be accurate to 2 hundredths of a second. The undersigned declares that, should a single piece from a batch (from the same house) fail, he will waive payment. To execute these adjustments, simply send the box numbers and the balance cock screw.

It would have been impossible for Switzerland to industrialise without a system of patents, and hand-made watches could never compete with mass-produced American products. Paul Perret’s revolutionary watch regulation machine enabled factories like Longines, Zenith, Tavannes and Eterna to produce some of the best watches in the world by the turn of the century. A new generation of watchmakers became industrialists even as their fathers refused to abandon the small workshop approach. But the industrialists soon faced a threat of their own: the rise of the cartel.

Disrupting the cartel

On November 3, 1895, the Swiss watchmaking industry was rocked by the announcement of a syndicate of balance spring producers. Perret’s balance spring tools had set the industry in motion, but the balance spring cartel threatened to stop production if their price was not met. A conference was held in La Chaux-de-Fonds on May 11, 1898, to establish a rival spring factory to break the cartel. Incredibly, it was Paul Perret who stepped up that night to announce a revolution that could save the industry once again.

Only one Nobel Prize related to watchmaking has ever been awarded: Charles-Édouard Guillaume’s 1920 prize for “precision measurements in physics” due to “his discovery of anomalies in nickel steel alloys.” Working at the International Bureau of Weights and Measures near Paris, a combination of serendipity and experimentation by Guillaume revealed in 1895 that certain alloys of nickel and steel were impervious to changes in temperature and magnetism. A true man of science, and a descendant of Swiss watchmakers, Guillaume openly shared his work.

-

- Paul Perret’s announcement of Invar balance springs. FH (1898). Perret was able to convince the attendees that Invar balance springs could not only replace the steel springs of the cartel but could also enable simple balance wheels to achieve chronometer-level performance. But the meeting also resulted in a commitment to create the Société Suisse des Spiraux, a factory to produce conventional steel springs.

Perret learned of Guillaume’s work from his friend Paul Berner, head of the watchmaking school in La Chaux-de-Fonds. He immediately requested a sample and was “struck ill” when he found that the stiffness of a spring made from the material increased with temperature, making the balance oscillate faster. Perret realised that the right alloy could compensate for temperature changes in a simple balance, enabling unprecedented levels of accuracy in mass-produced watches. When he arrived in Paris to share the news, Guillaume announced that he had already discovered an alloy with the right characteristics.

This was what Paul Perret revealed on stage in La Chaux-de-Fonds: the nickel-steel alloy, soon named Invar, could not only allow Swiss factories to break the cartel’s grip but also to leap forward in quality. Hedging their bets, the watchmakers voted that night to fund a conventional spring factory of their own. But Perret seized the opportunity to revolutionise the industry once again, soliciting funding to build an Invar balance spring factory in Guillaume’s home town of Fleurier.

-

- The Campyloscope was still in use in the 1940s. JSDH (1944)

Paul Perret died of a sudden illness on March 30, 1904. He spent the last years of his life overcoming many challenges to bring Invar springs to market, including a shortage of workers, issues with durability, and the quality of the alloy available. But the thermo-compensated and anti-magnetic alloy proved its worth in Observatory tests after his death and was soon adopted by the largest factories, including Omega, Zenith and Longines. Guillaume continued to improve the alloy, as did Reinhard Straumann, and nearly every modern watch follows Perret’s concept. Although Guillaume insisted on sharing the credit with Paul Perret, the Nobel Prize omitted to mention his collaborator, as did commentators after his death.

-

- Paul Perret’s obituary. JSH (1904)

Celebrating the disruptors

Innovators like Paul Perret always face criticism and scorn, especially when they threaten the establishment to such an extent. The same pattern can be seen with disruptors like Lépine, who transformed watch movements in the 18th century, P.-F. Ingold, who was run out of three countries for proposing mechanical production in the 19th century, and Armin Frei, who proved that a quartz wristwatch was possible. Perhaps it is too much to expect the establishment to embrace such fundamental challenges, but we should be open to them. After all, internal disruption has kept watchmaking viable in the face of external disruption for centuries!