The French brand Pequignet has now developed its own ‘basic’ movement—an incredible and original ‘house’ calibre with a very bright future

Surprise! Surprise! One of the most promising movements of this decade is being created not in the valleys of Swiss timekeeping but rather on the other side of the border, in the French Jura—more precisely in the town of Morteau.

The ‘assemblers’ of Morteau, who made up the heart of French timekeeping in the past, were decimated during the 1970s by the tsunami of Japanese quartz movements that swept over the land. Very few companies survived these floodwaters from the East. Among them, however, was Pequignet, a company formed in 1973 at the beginning of this huge crisis. This company succeeded in prospering thanks to the talent, the knowledge, and the special design sense of its founder, Emile Pequignet. In 2004, Emile retired to better devote himself to his many children and his horses. The reins of his brand passed to Didier Leibundgut.

Didier Leibundgut is himself a child of Morteau and of watchmaking. He still remembers with great pleasure his Sundays “at the factory” of his grandfather—the thousands of tick-tocks and the smell of leather. Later, in 1994, he became director of Zenith France, followed by international director of marketing for Zenith until the brand was acquired by LVMH in 2001.

Leibundgut (who had based his marketing strategy on the El Primero movement which was known as one of the best in its category—didn’t it drive the famous Daytona by Rolex?) was told, in a rather condescending manner, by his new employer that “we don’t sell movements; we sell watches.” In 2003, he left Zenith and purchased Pequignet.

Pequignet is not a manufacture, but an assembler. It is also a brand, the “last small brand in Morteau,” but one that enjoys a good reputation thanks to the particular design of its products and to the famous ‘Pequignet links’ made of movable segments that are a decorative feature and a distinctive sign of the brand. Over its history, Pequignet has received five Cadrans d'Or (Golden Dials) for the style of its timepieces. The enterprise, which employs 40 people, produces about 10,000 watches a year and 15,000 pieces of jewellery that are distributed in 25 markets. With an average price of 2500 ¤, Pequignet watches are fairly well divided between men’s and ladies’ models. Of the masculine pieces, 60 percent are mechanical timekeepers, equipped essentially with ETA movements, while chronographs are the brand’s specialty.

Calibre MVT 1111

The movement,

a ‘natural inclination’

Rather quickly, Didier Leibundgut saw himself caught up in its own ‘natural inclination’, or as he says, “the momentum was building to create our own movement”. He goes on to explain, “the real value in watchmaking—its reference value, that which makes it an artful skill—is the movement”.

When he speaks of the movement, Leibundgut takes on the tone of a poet, but it is quite clear that this is not just posturing. His passion and his dreams are real. “Timekeeping is a pastoral mÉtier”, he adds, “a mÉtier that is practiced in the silence and in the light. It is nearly religious in nature. We have just gone through a boom period that has perverted people’s values. The large luxury groups have made watchmaking into something noisy, ostentatious, violent, and arrogant. We are in a period of turgidity and excess, where ego reigns. Only Swatch Group and Rolex have remained industrial while being watchmakers. Only they have not gone crazy. Only they have continued to set correct prices, and to practice real watchmaking”.

In dreaming of his own movement, Didier Leibundgut would thus not want to make a noisy ‘helicopter’. On the contrary, he wants to return to the basics of timekeeping—to precision and reliability. But he also reasons like a marketing man. “In the current expansion of watches, the consumer is faced with a gigantic choice and is trying to understand what differentiates true luxury, beyond only appearances,” he insists. “Well, the distinguishing criterion is that of being a manufacture. To continue the ‘story’ of our brand, we thus must become, in our own turn, a real manufacture.”

Thirty-five years after the disappearance of the last manufacture in France, LIP, the stakes are enormous. But it seems the past is worth holding up, and with flying colours.

A blank page

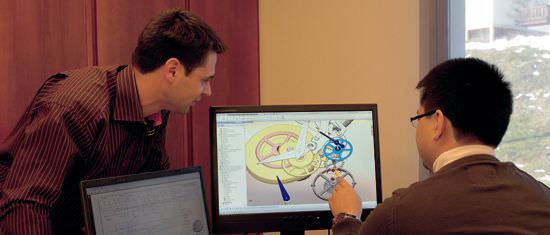

“We are starting with a blank page,” explains the duo who, under Leibundgut’s leadership, worked on creating this new movement, which was given the evocative code name of MVT 1111. Ludovic Perez, the head of the laboratory, and Huy Van Tran, in charge of research and development, formed an inseparable and complementary team.

Both men had long experience at CompliTime, a company specializing in complicated movements founded by Robert Greubel and Stephen Forsey. While there, they both worked on a number of realizations that made important contributions to contemporary timekeeping. As this company grew, however, the two watchmakers felt they needed a more personal adventure. When they met Didier Leibundgut, they were ready to come onboard because he offered them the rare opportunity to design a movement ex nihilo.

“What we wanted to do right from the beginning,” they explain, “was to achieve high performance in terms of power reserve, isochronism, torque, inertia for the precision, and especially great reliability.” Helped by modern technologies such as computer-aided design, prototyping, and control (the laboratory they created has the most advanced equipment available), Perez and Tran developed their project by re-inventing, as needed, all the component parts and their placement. In the end, the MVT 1111 bears no resemblance to anything in existence today.

Future integrations

Taking advantage of the possibilities offered by the large size of current watches, they designed a 13 3/4‘’’calibre (casing diameter of 30.6 mm). They placed the various elements in such a way that space has been left for the integration of different complications in the future. The single-directional winding oscillating weight is off-centre so that it does not hide the balance. On the back of the watch, the escapement wheel is thus visible.

In order to achieve the guaranteed elevated power reserve of 72 hours (in reality, more like 100 hours), they chose not to have several barrels but rather opted for a very large barrel that goes beyond the movement’s centre. With this choice, they minimized height (5.88 mm) while still having space to gradually integrate various complications on the same horizontal plane, without using additional modules. With reliability the key word, the two men tried to limit the number of parts, thus they found that a single barrel was a good solution. Abandoning the traditional index-assembly, they also selected a balance with a variable inertia screw, which allows for greater regulating precision while in the six positions. It also facilitates after-sales servicing.

With the same concern for ease in adjustment, maintenance, and after-sales servicing, the escapement wheel, like the barrel, is directly accessible and can be removed without touching the other gears (the gears are also completely designed in-house). Nothing or almost nothing of existing elements has been used—for example, the setting mechanism is entirely original.

Beating at the frequency of 21,600 vibrations per hour, the basic movement features central hours and minutes, a small seconds hand at 4 o’clock, a large instantaneous date at 12 o’clock with month display, and a power reserve indication at 8 o’clock.

While maintaining its same dimensions, this basic movement will expand to include a lunar phase display, an annual calendar, a GMT indication, and a tourbillon, while waiting for the creation of a totally integrated chronograph. The brand has already filed for several patents on its creation.

Planned for quantity production

“To gain reliability and precision, we have been able to work in complete freedom,” affirm both the designer and the prototypist of this remarkable movement. “From the beginning, everything has been designed so that the movement could be produced in quantity. When we started, all the essential planning was done, so much so that the road we are following is clear and direct.”

“It is the strength of a dream,” muses Leibundgut, “and I believe that we have truly succeeded in combining a respect for traditional and historic French timekeeping with a totally contemporary vision. By using design tools that have allowed us to work organ by organ, we have made a synthesis of the best of timekeeping at each step of the way. Everything we have accomplished is part of Haute Horlogerie and, by pushing the envel-ope of decoration to the maximum, we can rightfully claim to be a member of this group. But I also want to offer this movement at a price that will remain totally reasonable in relation to its high quality, its performance, its precision, and its reliability.”

Didier Leibundgut’s ‘good fortune’ is perhaps paradoxical in the current economic crisis—a situation that is marking a change of era and a return, let’s hope, not to the past but to the cardinal and founding values of watchmaking. Let there be less ostentation, more content, less noise, more reflection, less of the ephemeral, and more of the durable. This is what this wonderful adventure is all about. The old French word ‘PerpÉtuelle’, which was used by Breguet to designate a self-winding watch, was chosen to be on the dial instead of the word ‘automatic’.

At BaselWorld, we will discover the first prototypes of this movement, a calibre that marks the renaissance of the French manufacture. To see the first models to be equipped with this remarkable move-ment, however, we will have to be patient for a bit longer.

Source: Europa Star April-May 2009 Magazine Issue