What’s in a word?

Watchmakers don’t necessarily use the same terms to refer to the same components. In Vallée de Joux, for example, a balance bridge is called a balance cock. There are similar variations in the vocabulary of finishing, not all of which have translations. The act of polishing the cylindrical holes or sinks in which jewels are seated is known as noyautage, ébiselage or biseautage. The sinks themselves go by the name of gouttes or moulures. Travel along the Arc Jurassien and you will hear how the language of watchmaking changes, reflecting the unique character of each territory.

When it comes to the definition of finishing, however, consensus reigns. Finishing is the final stage of movement assembly, originally intended to eliminate burrs or scratch marks left by earlier operations. Today, professionals and enthusiasts alike are fluent in Côtes de Genève, perlage (circular graining) and sablage. Alongside these universal finishes are others, such as guilloché, invented by Abraham-Louis Breguet and reintroduced to contemporary watch buyers thanks to the tenacity of practitioners such as Georges Brodbeck, Kari Voutilainen and Yann von Kaenel. Technically speaking, these are examples not of finishing but of decoration created by etching lines into the metal.

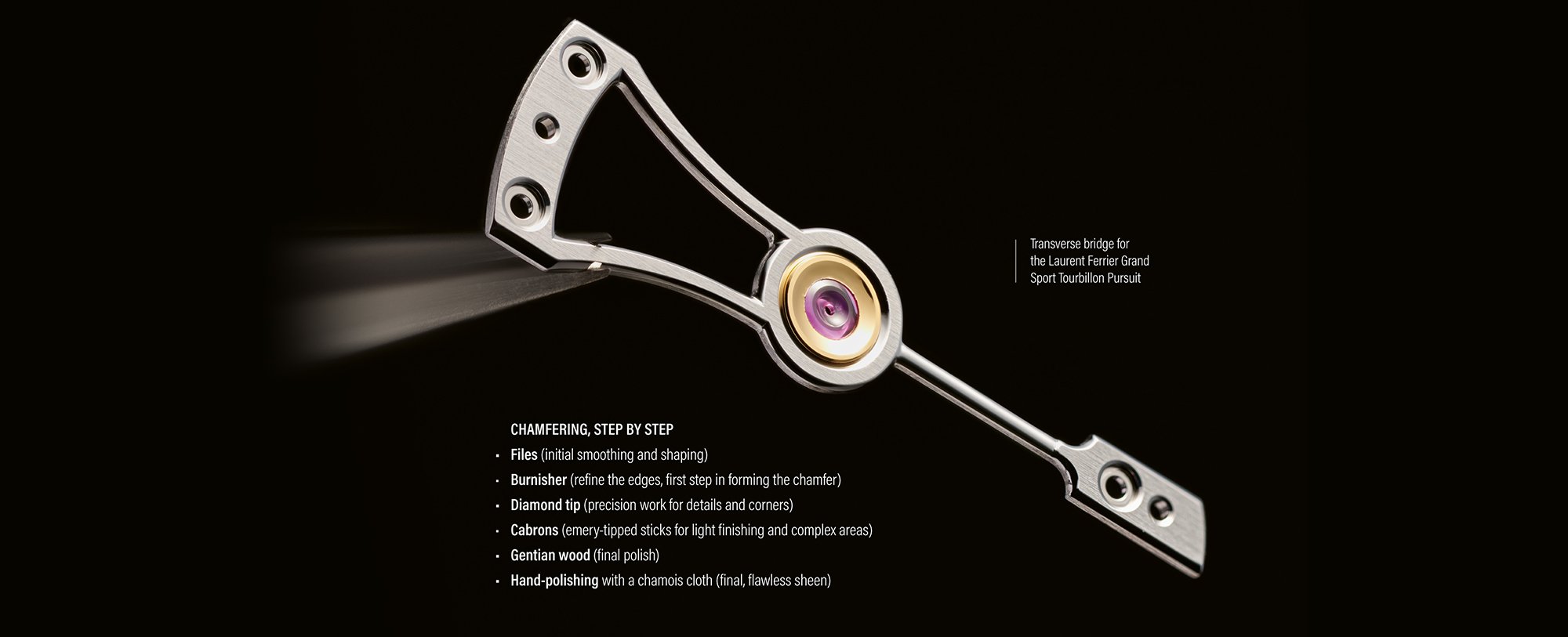

Finishing, in the strict sense, comprises various polishing techniques. Foremost among these are chamfering (anglage) and black polishing, also known as mirror polishing. Brushing forms a separate category. This can be vertical, such as the straight graining applied to the flanks of bridges, or flat, with techniques such as cerclage (fine concentric circles), snailing and sunray brushing.

Noëlle Grisard is an independent artisan who specialises in a complex form of chamfering known as berçage. An angle berçé is distinguished by a slight curve. “The stages and tools of berçage are the same as for chamfering,” Grisard explains. “I form several angles. The difficulty lies in creating a continuous line of light from the field to the surface.”

Finishing tools are, as one might expect, those of a metal polisher, starting with a set of more or less abrasive files. Other tools are burnishers (flat, smooth files used to harden a surface), wooden buff sticks or cabrons tipped with emery paper of varying fineness, and a selection of natural pithwoods such as beech, gentian and elder. The sheen given to bridges, wheels, even screws, imparts striking contrast to the finished movement.

The seeds of renewal

Passed from generation to generation, watchmaking has its fair share of urban legends whose origins are lost in the mists of time. One of the most enduring is that an exceptional timepiece must be the work of one and the same artisan, from conception to the making and finishing of each part.

The Old Watchmaker (1890), an oil on canvas by Edouard Kaiser, conserved at the Fine Arts Museum in La Chaux-de-Fonds, is an eloquent illustration of an ideal that persists in the minds of many collectors. It shows a white-bearded man at his bench, surrounded by tools, his entire being focused on the workpiece.

Still today, decoration and finishing are expected to mirror this vision. As Giulio Papi, co-founder of Renaud & Papi (now owned by Audemars Piguet) reminds us, hand-finishing serves to “highlight the excellence of the work performed at earlier stages.”

In this light, independents have much to gain from opening their ateliers to their more curious collectors. The dialogue thus engaged stimulates these artisan-creators while visitors are further convinced of their ideal of the talented watchmaker: a brilliant engineer as much as a skilled craftsperson. Not forgetting that this “open door policy” is a means of directly selling production that rarely exceeds a few dozen watches a year.

It is a path many young watchmakers aspire to follow, encouraged perhaps by the experience of producing their “school watch”. In order to graduate, every student in their final year of watchmaking school must design and create a watch, entirely by themselves. In addition to being a fabulous gauge of individual capacity, the experience helps forge an independent mindset.

The success encountered by competitions such as the Young Talent Competition imagined by François-Paul Journe is proof of the upsurge of interest in “hand-made”. For the monopusher chronograph that earned him the title of Meilleur Ouvrier de France 2018 in the precision techniques/watchmaking category, Sylvain Pinaud designed, made (using a jig bore and a lathe) and finished every part himself, unaided. Such a herculean task is the result of months of solitary apprenticeship: or in Pinaud’s words, a “crazy amount of work!”.

A conversation between tradition and innovation

Advances made in computer numerical control (CNC) machining have repercussions for finishing. Today’s multi-axis machines maintain precision at micron level and can produce all types of chamfer — 45 degrees, convex, even bercé — without any input from the human hand.

Does this mean hand-finishing is doomed to disappear or, on the contrary, can tradition and “CNC modernity” make good bedfellows?

Philippe Narbel is the founder of Manufactor, a company specialising in watch decoration. He believes the profession of chamferer will evolve into that of specialised polisher, “as there is no longer any need to form the chamfers with a file.”

Another Swiss company, Crevoisier, which supplies machine-tools for decoration and finishing, has developed an innovative solution: a robotic arm memorises the forces applied by a human polisher then precisely reproduces them. In an interview to Swiss daily Le Temps, CEO Philippe Crevoisier refutes the notion that he is “taking jobs from polishers”, instead emphasising that this technology makes up for a lack of qualified staff while having robots perform repetitive tasks that cause tendinitis and other strain-related injuries.

While automation is redefining certain professions, it hasn’t replaced human expertise. Every day, Manufactures and independent workshops are striking a balance between tradition and innovation, guided by individual choices and industrial constraints, to shape the world of movement finishing and decoration today.

Rexhep Rexhepi: a constant learning curve

Rexhep Rexhepi is symbolic of the new wave of independent watchmaking. He took the 2022 Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève Men’s Watch Prize for his Chronomètre Contemporain II, having already won in the same category in 2018 for the first version of this remarkable watch. Behind his relaxed and smiling demeanour are some challenging years and decisive choices.

Rexhepi arrived in Switzerland from Kosovo in 1998, aged eleven. Four years later, he began an apprenticeship with Patek Philippe where he mastered the foundations of his craft. Eager to hone his skills, he completed his training at the movement-making thinktank BNB Concept, founded by Mathias Buttet, Michel Navas and Enrico Barbasini. It was here that he discovered innovation applied to complications and learned the rigour needed to produce complex movements.

A new opportunity to test his expertise came in the early 2010s when he joined the independent atelier of master watchmaker François-Paul Journe. This immersion in a world where the highest degree of craftsmanship serves an avant-garde vision of haute horlogerie would leave an indelible mark, instilling in him the meaning and importance of design, flawless execution and the constant pursuit of excellence.

Inspired by this experience, Rexhepi was soon nurturing his own ambition to put his stamp on the watch world and in 2012 took a leap of faith with the launch of Akrivia, a name taken from the Greek word for “precision”. However, the reality of striking out alone soon made itself felt as, for almost three years, he struggled to find buyers for his watches. Undeterred, he worked harder than ever, driven by an unshakeable passion for his craft. He refined his style and developed an identity, always seeking to create truly authentic watches.

Two people would have a decisive influence on his journey as an independent watchmaker. The first was Dr Michael Tay, managing director of Asian retail giant The Hour Glass who encouraged him to sign a watch with his own name: a decision that established Rexhepi as a creator, distinct from Akrivia. The second was legendary casemaker Jean-Pierre Hagman who joined the workshop in 2019, bringing the benefit of his unparalleled expertise in customised precious metal cases to Akrivia’s timepieces.

We visited Rexhep Rexhepi at Akrivia’s workshops in Geneva’s Old Town, and were struck by the demand for excellence at every stage in the creation process. The watchmakers decorate each movement themselves. The hands of the RR CC II, for example, are given three separate finishes: berçage and black polishing for the hand itself and ébiselage polishing of the seat for the post. The same applies to barrel bridges, with ébiselage of the sinks for the screws and jewels, chamfering with inward angles on the contours and Côtes de Genève on the upper surface.

Three questions to Rexhep Rexhepi

Are there any limits to traditional finishing and decoration?

I’m not sure we can really talk about limits. There is no such thing as perfection. A piece can always be reworked or improved. Techniques are constantly evolving. You can hone each gesture, learn new methods, try subtle adaptations. Watchmaking demands patience and commitment. The longer you spend, the greater the potential to progress. It’s an infinite learning curve and that’s what makes it so beautiful.

Is there opportunity to innovate?

Absolutely! Innovation is how artisanal professions evolve. To give an example, the seconds register on the Chronomètre Contemporain II in platinum presents a gravé-gratté decoration. Rather than a graver, I used a knife to etch thin lines, one by one, like woven fabric. A layer of translucent grey enamel is then applied. As the light changes, it creates variations that suggest a texture similar to meteorite.

If you could make one wish?

To be able to work without time constraints and experiment freely, without any pressure or deadlines, and explore the full potential of every idea. To be able to test various materials, observe their reactions and perfect each detail without rushing. Then it would be possible to adopt a different approach, explore alternatives and keep experimenting until you obtain the ideal result for a material that had seemed inadequate, unstable or unpredictable. Such complete freedom would pave the way for truly bold creations, where the artistic process would have no limit.

Laurent Ferrier: the right balance

Stepping into the calm and quiet of Laurent Ferrier’s workshops in Plan-les-Ouates is like stepping outside time. Here, the watchmaker’s art is expressed at a level rarely achieved, finishing each part expressly to enhance the silhouette of the movement as a whole. “We look for balance between form and finish,” Ferrier explains in a tone that is both clear and firm. “There is no excessive satin-brushing, Côtes de Genève or bouchonnage. We want the contours of the calibre to be visible.”

The Classic Evergreen is the perfect illustration of this desire for harmony. Its movement, with micro-rotor and natural escapement, features a bridge whose elongated form suggests a swan’s neck while the balance bridge has the curved shape of a hammer in a chiming complication. Laurent Ferrier — who spent his career in the external parts department at Patek Philippe where he worked on several iconic projects including the Aquanaut — has developed an acute sense of horological design.

Viewed under a loupe, the finishing of the Evergreen’s movement is a captivating sight: the Côtes de Genève on the bridges, the delicate circular graining on the plate, hand-polished screws, smoothed gear spokes and inward angles executed with superhuman precision. As with the Grand Sport Tourbillon, forms and decorations cohabit in complete harmony.

This pursuit of excellence is similarly evident in the workshop structure, with an engineering design bureau, the watchmakers and a decorations department that employs almost half the total number of staff. Every detail counts: the meticulous chamfering, the patiently executed straight graining, the perfectly regular rhythm of the Côtes de Genève, and of course the black polishing, a true signature of an artisan watch.

Every gesture perpetuates a tradition while gnawing at the limits of perfection. The brand shares this expertise in a series of short films that offer a glimpse of the work accomplished here. They are an invitation to discover the world Laurent Ferrier has created, where the movement’s beauty comes as much from its mechanisms as from the emotion instilled by each artisan.

Sylvain Pinaud: an artisan’s pace

With two watches in his catalogue – the Origine and the Chronograph Monopoussoir – and already two Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève prizes under his belt, Sylvain Pinaud stands out as one of the most talented independent watchmakers of his generation.

His atelier, which is home to three watchmakers and two decorators, is in Sainte-Croix. His neighbours are automaton-maker François Junod, restoration specialists Dominique Mouret and Nicolas Court, and dial marqueteur Bastien Chevalier.

After earning his stripes at Franck Muller, Sylvain Pinaud joined Dominique Mouret where he spent his days restoring clocks. It was through contact with these singular objects that he forged his own sense of aesthetic, marked by an appreciation of the proportions and harmony that characterise the watchmakers of yore. Les anciens as he calls them, and there can be no doubting the respect tinged with admiration that he feels for his predecessors.

2018 would mark a turning point in Sylvain Pinaud’s career, when he was awarded the title of Meilleur Ouvrier de France. Already, his transformation of an ETA 6497 calibre into a monopusher column-wheel chronograph demonstrated his eye for detail and perfect mastery of finishing techniques. The project, months of solitary labour, offered not just a challenge but the unique opportunity to develop his own watch. It would be this foundational experience that convinced him to pursue his idea of creating his own brand.

During our visit, we were able to observe the precision finishing of a ratchet screw with chamfering and black polishing on a block of zinc. Endlessly repeated, these meticulous techniques demand hours of patience. Sylvain Pinaud confesses his fascination for the balance wheel: “a quest that has occupied watchmakers for the past four hundred years.”

-

- Circular-brushing wheels and black polishing require the expert precision of the artisan.

As evening falls, in the softly lit workshop, he places the balance wheel he has just finished decorating under the microscope. The silence is palpable. We hold our breath. He skims a moist cotton bud over the perfectly polished rim, observing how it reflects the light, then, in a murmur, delivers his verdict: “I find that beautiful.”

-

- Atelier Sylvian Pinaud, Sainte-Croix

“I draw simple forms which can be hand-made without CNC machines,” he explains. He advocates an approach whereby, two hundred years from now, each component can be identically recreated. On his monopusher chronograph, surfaces capture then reflect the light, changing colour as they do to appear black, grey or white: the result of the ancient and constantly evolving technique of black polishing. Sylvain Pinaud does more than make watches. He is forging a legacy that will inspire future generations. “A watch is a building, its parts must be in harmony,” he concludes before adding, with a smile, “I could look at the Origine for ever and never get tired.”

La Fabrique du Temps Louis Vuitton: look to the future

Since 2023, La Fabrique du Temps Louis Vuitton has orchestrated the design and manufacture of Daniel Roth watches. Three have already seen daylight and demonstrate a profound attachment to horological craftsmanship. At the workshops, in Geneva, precision combines with expertise and respect for the past meets a vision of the future.

We are greeted by Enrico Barbasini, co-founder of La Fabrique du Temps with Michel Navas, and immediately immersed in a world of excellence. “We wanted inward angles as well as bridges with angles berçés and straight-graining by hand using a buff stick,” he explains as he shows us the DR001 calibre of the Tourbillon Rose Gold, unveiled in 2024. No mere embellishment, decoration accounts for “more than two-thirds of the work.” Each component is painstakingly finished to embody the particular elegance and refinement of Daniel Roth. The DR001 is a shaped movement, distinguished by large wheels and a linear click, both characteristic elements of haute horlogerie.

La Fabrique du Temps shows that it is possible to respect a heritage without becoming locked in tradition. Michel Navas’s belief that “beauty should be measured not by the number of inward angles but by the movement’s construction” is a stance against the stylistic one-upmanship within haute horlogerie today. Introduced in 2025, the extra-thin calibre DR002 illustrates this determination to marry sophistication and rigour, without excess.

While tradition is at the heart of the workshop, there is space for modern methods, too. Certain operations, such as polishing components or forming chamfers, are prepared using automated means then completed by a watchmaker, using time-honoured methods and hand tools. Guilloché, a hallmark of a Daniel Roth watch, illustrates this cooperation between machine and craftsman, innovation and tradition. In its efforts to safeguard this expertise, La Fabrique du Temps has bought and restored three rose engines, dating from 1850 and 1935. Operated by a skilled master guillocheur, they can produce a pattern of Clous de Paris or hobnails separated by just 0.3 millimetre.

-

- Traditional rose engine at La Fabrique du Temps, Geneva

Away from dogmas, Barbasini and Navas push back the limits of possibility and perpetuate ancient skills while embracing innovation. Michel Navas explains how specific parts of a Daniel Roth movement are “decorated on the reverse so that the watchmaker can appreciate their finish at every stage.”

The full force of this innovation is apparent in the watches that La Fabrique du Temps imagines for Louis Vuitton. Launched in January 2025, the Tambour Taiko Spin Time Air Antipode is truly impressive. After reinventing the jumping hours display for Louis Vuitton in 2009, Navas and Barbasini let loose a haute horlogerie tidal wave. As Jean Arnault, Louis Vuitton Director of Watches, observed, “without the Spin Time, we would not have embarked on this adventure in the same way.”

The sixth and latest model in the Tambour lineup, the Antipode expresses the theme of travel, the very essence of Louis Vuitton, in a novel way. Twelve cubes appear to float around a central dial to simultaneously display local time in 24 time zones. Above each cube, initials corresponding to the names of two cities, twelve hours apart, lend a cosmopolitan feel. Developed and produced in-house, the movement’s exceptional standard of finishing is on a par with the Taiko case, which is crafted at La Fabrique du Temps. This world-time complication is characteristic of the avant-garde spirit that drives La Fabrique du Temps Louis Vuitton.

Atelier Voutilainen: in praise of harmony

Overlooking the town of Fleurier, in Val-de-Travers, the Voutilainen workshops are where Finnish watchmaker Kari Voutilainen — winner of the 2024 Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève Men’s Watch Prize for the KW20i Reversed — continues a journey marked by artistic constancy, respect for tradition and technical innovation. Even the most sceptical leave his workshop convinced by the sincerity of his vision.

On this particular day, two of the staff are hard at work applying five different finishes to ratchet screws: straight-graining the sides, polishing the shank, black-polishing the head and executing the various chamfers, including on the inside of the slot. “It’s a labour of love!” one of them jokes, pointing to the fifty-some screws in the latest KW20i Reversed.

Each movement comprises several hundred components, which are precisely conceptualised by the engineering design bureau. Decoration, however, speaks a different language. One that is transmitted orally and acquired through experience.

Freshly machined plates and bridges are pre-decorated then sent to the watchmakers for preliminary assembly. Now the decoration can begin in earnest, the artisan working by hand and by eye, unrushed, entirely centred on the component in front of them.

One of the artisans, who has been with Voutilainen for 17 years, showed us how Côtes de Genève are formed using a traditional hand-operated machine. He also explained the importance of choosing the right wood for chamfers, based on density, from guayacan, which is the hardest, to the softer elder and gentian, or boxwood, essential for fine polishing.

He ended his demonstration by polishing a sink, where a jewel or screw sits, using his artistic sensibility to judge the angle of each stroke and subtly play with the incidence of light rays on the metal, guided by the high standard of quality that prevails throughout the workshop. Experience and intuition take precedence over technical drawings. The best representation of this is the 20th Anniversary Tourbillon, a celebration of 20 years of independence for the workshop, which was founded in 2002.

At another bench, a watchmaker was engrossed in polishing and hardening winding stems on a 1960 machine that was built by H. Hauser in Biel.

Even when the pressure mounts, where other workshops might insist on the need to get watches shipped, at Voutilainen, the atmosphere is serene. The close-knit team regularly meet for discussions, convinced that a job well done takes time, skill and perfectly mastered expertise.

What about Kari Voutilainen himself? What hopes does this independent watchmaker nurture? “To preserve and perpetuate traditional skills while maintaining a coherent aesthetic,” he replies. A former teacher at WOSTEP (Watchmakers of Switzerland Training and Educational Program), he insists on the importance of technical expertise. “Sometimes we put too much emphasis on finishing. It’s the harmony between the technical and the aesthetic that makes a truly exceptional watch.”

Artime Créations: an architectural vision

In 2010 watchmaker Manuel Thomas established Artime SA, specialising in movement decoration. The arrival, in 2018, of Stéphane Maturel, a watchmaker and movement constructor, marked a decisive stage in the company’s development with the creation of Artime Usinage Sàrl, this time specialising in machining. A new milestone followed in 2021-2022 when the group was joined by veterans of Renaud & Papi and other leading names in the industry. Together, Manuel Thomas, Stéphane Maturel, Fabrice Deschanel, Emmanuel Jutier, Didier Bretin and Claude Emmenegger are behind Artime Créations SA. The company has launched its first watch, the ART01, in addition to developing movements and creating decorations for third parties.

We met some of the team in Les Brenets, where the group’s decoration workshops are based. They are convinced that “innovation in decoration comes from the integration of technical, machining and design constraints.” In other words, “the same as with cooking”, “combinations of new materials and processes” open up new avenues to explore.

They’re upfront about the role computer numerical control (CNC) machines play in the finishing process. By way of example, they show us a technical drawing. At the point where two surfaces meet, the inward angle is machined at 45 degrees. The flanks need a picage finish, a technique that uses a wire or a file and is impossible to achieve on a machine. It is a perfect illustration of Artime’s engineer-meets-artisan approach, which integrates technology but doesn’t neglect the expert human touch.

The transparent movement architecture (there is no mainplate) of Artime’s 2023 inaugural creation, the ART01, testifies to a highly developed sense of horological design and a perfect mastery of technique, brilliantly illustrated, for example, by the sophisticated finish given to the three-armed tourbillon cage. Artime harnesses its expertise in techniques such as chamfering and black polishing to instil its creations with remarkable depth and finesse. Mechanisms become art, where every detail matters and the end result is a source of constant wonder.

One final demonstration awaited us, this time of a novel finish which Artime has named poli damier (chequerboard polish). The company’s process designers have devised a metal grid which the artisan fixes, by its four attachments, to the bridge to be decorated. The metal that is visible through the holes in the grid is hand-polished to create a negative chequerboard pattern. The result is entirely original.

No doubt the ART02 and ART03, scheduled for 2025, will be a chance for the Artime team to show off more of their talent… as engineers and artisans.