During the last few decades, watch design has passed through several successive phases. Until the 1970s, it was difficult to speak of ‘design’ in the strict sense of the term. The design and realization of most watches resulted from the to and fro of a brand’s in-house creative team and what their subcontractors could propose. Taking what was available from the catalogues of its suppliers, a brand would integrate pre-existing dials, cases, bracelets, and hands into its creations. The final ‘design’ was therefore a compromise between a brand’s own ideas and what it could obtain from its various parts providers.

This practice was more or less discarded with the appearance of the first true designers. Among them was the emblematic Gérald Genta. By creating the Royal Oak in 1972, the Nautilus in 1977, the Bulgari-Bulgari watches, followed by the Omega Seamaster and Constellation collections, Genta opened new avenues for the industry. More importantly, he demonstrated that a watch’s success was very closely dependent on its design. These new avenues then opened the way for others to also become ‘designer stars’.

In the middle of the 1980s, this first generation was succeeded by a second generation of young designers who were determined to make their own mark in the universe of time. Among them were Hysek, Rodolphe, and DiModolo, to name only a few. This group of designers then became the stars that the brands were no longer reticent to mention. On the contrary, they even began promoting their timekeeping ‘stars’. As one example, Longines introduced a Rodolphe collection and even used the designer’s own image in its advertisement campaign. This new fame encouraged this second generation of creators (who are now in their fifties) to establish their own brand or to set up their own production facilities.

Today, we are moving into a third phase. Today, the designer has been asked to be more discreet, in favour of the brand, which has again become the star. Thus, the latest generation of designers (35 to 40 years old) is again working in the shadows of the brands. Just as talented as their predecessors, their priorities have, however, changed. They are not there to affirm and impose their own style but rather to conform to the famous DNA of the brands for which they work. The pendulum has swung again.

To learn more about these new designers, we talked to several of them: Antoine Tschumi at Neodesis, Xavier Perrenoud at Ateliers XJC, and Nicolas Barth Nussbaumer who, along with Manuel Romero, founded the company, White SA.

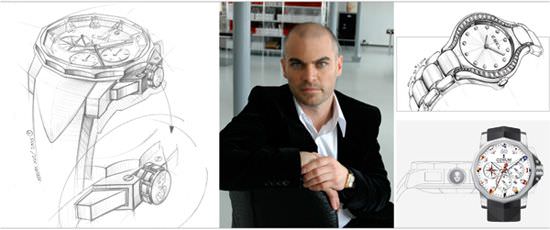

Antoine Tschumi at Neodesis

Done with the divas

The first thing that these men have in common is that they were all born and have established their ateliers in the heart of the industrial lungs of Swiss timekeeping. Home to most of the sector’s subcontractors, this famous region in the Jura Mountains includes the towns of Le Locle, La Chaux-de-Fonds, and NeuchÂtel.

All of these young people have also carried out their studies in this area. Antoine Tschumi (born in 1974) studied jewellery and stone-setting at the Art School in La Chaux-de-Fonds; Xavier Perrenoud (born in 1970) undertook technical training at the Technicum in Neuchâtel; and Nicolas Barth (born in 1972) studied jewellery making at the Art School in La Chaux-de-Fonds. In the case of Manuel Romero (born in 1968, and a geologist by training), he is not a designer in the exact sense of the term but is part of a united and skilled duet that he formed with Barth.

How do these men explain this tropism? “Contrary to what has happened in many other industries, watch design has remained in Switzerland. This is because people here know the brands and the brands themselves find a certain savoir-faire and humility that they do not find anywhere else,” explains Perrenoud, adding, “Here, the designer doesn’t think of himself as an artist, but rather as an artisan. That makes all the difference.”

For Tschumi, the explanation resides in the collective nature of watch design. “It is a team effort. It is a type of work that closely and increasingly combines technology and styling, content and form, which are inseparable. More and more, it is about revisiting a brand’s tradition, which means thoroughly understanding it. There is no room for a diva who brings in a design—specifically his or her own design—with the attitude of ‘take it or leave it’.”

“We don’t make ‘designer’ watches or ‘architectural’ watches,” adds the duo of Barth and Romero. “Our approach remains humble and we keep a low profile. This allows us, paradoxically, to be extremely demanding and to go far, in fact very far, into detail.”

Xavier Perrenoud at Ateliers XJC

On the job training

This obvious humility (our designers are nonetheless justifiably proud of their creations) is perhaps explained by the fact that, for their generation, there was no formal training to learn how to be an ‘industrial designer’, unlike what is available today. The Ecole Cantonal d’Art in Lausanne, for example has just created a MAS Degree in ‘Luxury’ design in collaboration with skilled designers that include Xavier Perrenoud.

“I learned on the job,” says Perrenoud who, after graduating from the Technicum, went straight to work for Pierre-AndrÉ Aellen, a former product director at Omega, who had created his own agency. “I spent eight years learning my trade before opening my own business in 1998.”

A similar road was followed by Tschumi who, after having worked in stone-setting, “entered watchmaking” in 1992 when he joined the very successful Gucci Timepieces. Following Gucci, he worked at the private label company, Walca, before launching out on his own in 1997.

After leaving school, Barth went to work for two watch designers who belonged to the preceding generation, Rodolphe and DiModolo, before setting up his own company at the age of only 24. The most surprising path was followed by Romero. A geologist and then a teacher, he decided to try his luck in watchmaking and joined Omega in 1996. He later became Director of Sales at the rapidly growing Calvin Klein watch brand. He was then appointed Director of Certina, where he met Nicolas Barth after asking him to design watches for the brand. A year and a half later, in 2003, he “took the big step” and joined Barth in creating White SA. “I gave up a golden situation and divided my salary by four,” he explains, “but it was worth it.”

The role of strategist

“The fact that I have worked with the brands allows me to totally understand the briefs that they submit to us,” adds Romero. “I understand where they are coming from and I have a clear vision of what any given brand is all about. I have visited them all in the field.”

This in-depth vision of the brands is undoubtedly the most important element that explains the success of this generation of designers. “Our generation tries, above all, to understand the essence of the brand we are working for,” adds Perrenoud, “and to never lose sight of it in our projects. I am not there to advance my own personality but rather to advance the brand. We have to absorb this essence and work towards it. This does not mean less creativity. Rather, it requires a greater overall understanding than before. Earlier, the marketing aspect was more important than the product. We are fortunate to be part of a general movement that now puts the watch back at the centre of attention. This is why even the slightest detail is so important.”

“The designer has become, whether he likes it or not, a strategist,” muses Tschumi. “In the beginning, that was not our role but so many brands do not have a real long-term view of things. The designer is also there to bring substance, consistency, and emotion to the product.”

This opinion is shared by Barth and Romero. “Many brands send us all the same brief, which is totally influenced by the ‘watch star’ of the moment. When, for example, Richard Mille and Hublot started to become really successful, we received only this type of thing in the briefs from the brands. Our role therefore is to refocus the brands and remind them of their fundamentals, and to develop them without becoming totally obsessed by the current trend.”

Nicolas Barth Nussbaumer and Manuel Romero at White SA

A process of fusion

This pragmatism undeniably explains the many successes of this new generation of ‘discreet’ and conscientious designers. Compelled to silence by the brands not wishing to reveal their exterior collaborations, we are not able to publish the past and current projects of these designers. (You would be surprised to learn some of the names.)

On the other hand, some brands do permit their designers to divulge this information. Among the brands that White SA designs for, for example, are TAG Heuer, Louis Vuitton, BÉdat & Co., George Jensen, Chaumet, Villemont, and Maurice Lacroix (for which White creates the entire collection). Amongst his clients, Xavier Perrenoud can mention the brands Ebel and Corum, with which he has developed a strong relationship over the last few years.

As for Antoine Tschumi, he has or is taking part in a number of ventures including: participation in the complete overhaul of Vulcain and Jordi; designing the Indicator by Porsche Design or the Opus 6 of Harry Winston; and creating a second CT Design structure with Complitime.

Tschumi’s association with Complitime (owned by Greubel Forsey) began five years ago and is emblematic of the close partnership between a designer and a company known for the advanced technology of its products. It is clear that, for a firm such as Complitime SA, there is no question of designing the shape without considering the technical aspects, since they are closely interwoven. The design process thus must treat both elements as a pair.

You can see the same approach—and how!—in the striking Mémoire 1 by Maurice Lacroix (for more information, see Europa Star issue 2.08) of which White was intimately involved. The objective of this exceptional project was to closely combine a totally new function in watchmaking (a mechanical memory) with innovative design and unparalleled readability (the same hands indicate the time and the chronographic functions on request). “Everything came out of the brief,” state Barth and Romero. “This creation is the fruit of discussions between the brand, the constructor, and the designer. From the start, everything was integrated into a fluid process whose parameters were continuously adapted and modified. Between the technical and design work, a common language was born. This language crystallized around the conical shape that formed the basis of the piece and that we find in all its aspects. The Mémoire 1, right up to the treatment of its surfaces and decoration, is not the result of compromise but rather came from a joint effort, a process of fusion.”

Attention: everything is possible

In this process, the technical tools (among others, three-dimensional modelling coupled with sophisticated computer command and control equipment) used in watchmaking today are, as we might expect, a great help. “Today, for example, when it comes to creating cases, we can do more or less whatever we want,” affirms Romero, adding, “If we ask the question, ‘is it doable?’ then we restrict ourselves and will thus not go far enough. We don’t work, therefore, only as a function of what we know how to do. We try to go beyond these boundaries.”

“Nowadays, it is true that technology and the unabashed economic health of the watch industry allow us to radically explore new avenues of research,” declares Tschumi. “The possibilities, in comparison to what was conceivable only ten years ago, are really unbelievable. The danger for the brands, however, is a loss of substance because it is difficult for them to resist the temptation of giving in to fashion trends in the hopes of having a big hit. This is even more important for the new brands. If we look at a company such as Hautlence, for example, which is consistently constructing its brand with a view towards the long term, how many other brands do we see that will make an immediate splash only to then fade away?”

This same sentiment is echoed by Perrenoud. “We see many caricatures of watches at the moment. Many brands are being born and some are interesting and even show potential, but most of them do not really think about their identity over the long term. All too often, someone will ask a designer to create a case while this person should really be looking beyond the mere case. If the designer is also involved in the movement, this gives the piece a more coherent and global nature. This is even more important since we are witnessing the disappearance of the dial and a marked evol-ution in a watch’s functions and how they are displayed. What is happening today is that constructors are proposing movements to the brands that are often totally spectacular, yet the cases are only considered secondarily.”

“Ah yes, it is harder to gain acceptance for something daring without being commonplace,” say Barth and Romero, “because that presupposes more advanced work, in great detail, that aims for balance, readability, and harmony.”

Searching for harmony

This particular approach, along with the search for harmony and pleasing proportions, is common to all three of the design offices we visited. It is revealed in the similar methods that they follow in the act of creation. Even though the trend is to use advanced techno-logy, this intermediate generation relies primarily on hand design. They only use 3D modelling at the end of the design cycle. “The harmony of proportions is a fundamental notion,” insists Perrenoud. “This is the reason that I always begin by working by hand. Drawing on paper not only allows me to think globally about the piece, but it also permits me to create the conditions for a dialogue with the brand. If I don’t do this, I have the impression that I am cutting corners. It is only after this initial hand work that I use the computer. Then, when I enter the parameters and data, I know exactly what they correspond to. You have to recognize, however, that using 3D modelling is easier to sell than a hand-drawn sketch, even if it is only to show off.”

The same feelings were expressed at White. “We work in the old style. We do the real research by hand sketching. Later, we pass to more formal methods, first in 1:1 then in 3D. Our real treasure is our stock of 500,000 drawings. It is our reservoir of inspiration.”

“I always present three different solutions to the problem that I am asked to solve,” explains Tschumi. “The first addresses, in an in-depth manner, the codes of the brand. The second plays with these same codes, and the third solution makes them explode. This lets me understand and also makes the brand understand a product’s global potential. It also forces the client to enter into the creative process, without stopping only at an image. Many watchmakers don’t have the eye for a drawing. They get stuck on a single detail and do not see the overall picture. Presenting a brand with three different elements to look at allows the decision makers to adjust their strategy, which the designer, now a confidante of the brand, must then carry out.”

A collective art

This new role of ‘confidante in the shadows’ has also transformed the economic relationship between designers and brands. ‘Gone are the days of lifetime royalties’, the designers all agree. “The preceding generation, based on their aura, often exaggerated their demands slightly,” continues Perrenoud. “Most of the time, now, royalties are negotiated and combined into the fees, with added bonuses if the model is sold and is successful. But everything also depends on the business sense of the designer,” adds Perrenoud, with a smile.

When seeing the facilities that they have all created, there can be no doubt that they all have many talents. Antoine Tschumi’s Neodesis employs seven people: designers, case makers, project chiefs, and even an outside artist who participates in the creative process. Xavier Perrenoud’s Atelier XJC has seven versatile designers and direct partners who work together in creating the prototypes. White SA, employs nine people, all versatile designers and graphic designers, as well as one intern. “We learned a lot from our teachers and want to transmit our knowledge to others as well,” affirm Nicolas Barth Nussbaumer and Manuel Romero.

This generosity and willingness to share is truly felt when we visited their ateliers. It is also what characterizes their generation. Design is a collective art, even if the creation is not always a democratic process.

Source: Europa Star August-September 2008 Magazine Issue