hen Albert Bernet wasn’t working in the fields or tending to the cows on his farm in Val-de-Travers, he made movements for Neuchâteloise clocks. A profession learned at his father’s knee. The “Neuchâteloise”, a bulbous mantle clock, had once been a feature of every Swiss home. Now it, too, had all but vanished.

Henry Brandt’s film of Bernet had been commissioned in 1962 by Ebauches SA, the movement-making conglomerate that later became ETA, now owned by Swatch Group.

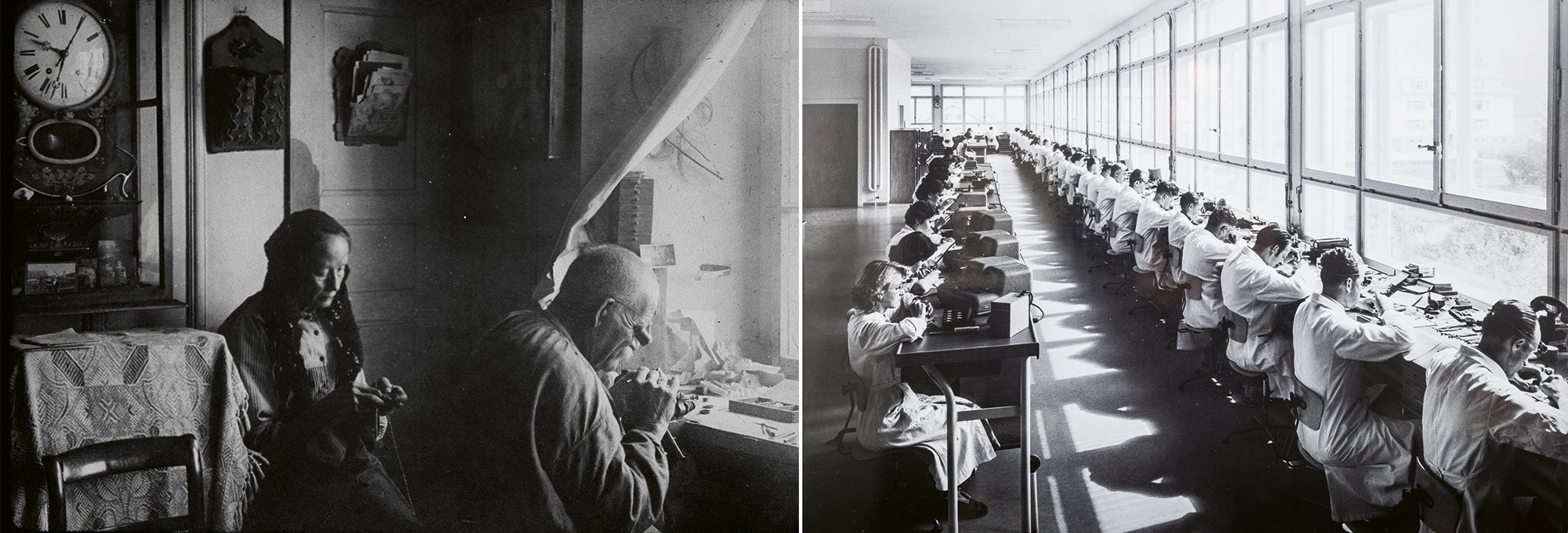

Years later, Brandt would recall how “the company that commissioned the film wanted a documentary about an old watchmaker; one of the farmer-watchmakers you used to find around here. Farmers by day, watchmakers by night and during the winter months. The idea was simply to have a record of this man who was old and going to die, who had spent his life making clocks, piece by piece. It was me who wanted to compare his way of working with what the industry had become.”

-

- Albert Bernet

- Photo Max Chiffelle, 1953

The film opens with shots of green fields and countryside. A portrait of a life lived at a human pace, in time with the seasons and work to be done. Abruptly, the scene changes to rows of factory workers, slaves to the clattering machines they hand-feed. A stifling vision of the semi-automation that was sweeping the industry.

-

- The “bare bones” of a Neuchâteloise clock – Musée des Mascarons, Môtiers

“They let me loose in one of their factories and I made a film that many saw as highly critical. This factory work seemed so terrifying then, so inhuman. Today it seems more paternalistic. At one point it looked as though the film would be rejected. It was extremely critical of the condition of the working class,” Brandt noted in 1975.

“It’s already fifteen years old. Of all my films, I’d say it’s the one that has aged the most. Things must be different now.”

-

- Scenes from Les Hommes de la Montre, directed by Henry Brandt (1964)

Les Hommes de la Montre indeed ends with the introduction of the first mechanised feeding system: the precursor – in 1964 – to today’s CNC. Machines are no longer semi-mechanical, fed by an operator at a pace they dictate, but fully automated. The film leaves its audience with a question: will technology free humans from their servitude to the machine?

What of the question today?

This vast question seems almost irrelevant at a time of growing AI domination. We have entered an unprecedented and as yet unpredictable stage. From muscular and mechanical, our “servitude” is now cognitive and cerebral. From the body to the mind itself.

Albert Bernet passed away in 1967 on his farm in La Jotte-sur-Travers. Sixty years ago. Almost three generations. Enough to declare the farmer-watchmaker dead and buried. Or is he? Little by little, this symbol is making a return.

-

- Photos Max Chiffelle, 1953

When Albert Bernet died, industrial watchmaking in Switzerland was at its height: shooting for the Moon but knocked back down to Earth by quartz, whose shockwaves were felt all the way to the Swiss valleys. Out of the ashes rose the conglomerates, empires and aristocracies that would dominate a landscape gradually turned over to luxury and mechanical one-upmanship. Paradoxically, the humble farm became the symbol of this rebirth. Look no further than Blancpain’s foundational tagline, set against the image of a farm where, supposedly, it all began: “Since 1735 there has never been a quartz Blancpain watch. And there never will be.”

Progressively, these mythicized origins became the mantra of “watchmaking regained”. And Albert Bernet one of the Saints of this rediscovered cult.

Rousseau’s invention

It’s commonly agreed that the myth of the farmer-watchmaker originated with Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who spent the years 1762 to 1765 in Môtiers, deep in the Val-de-Travers mountains – having been drummed out of Geneva where his books were burned. In Letter to M. d’Alembert he writes:

These happy farmers (…) employ the leisure that tillage leaves them to make countless artifacts with their hands and to put to use the inventive genius which nature gave them. (…) Never did carpenter, locksmith, glazier or turner enter this country; each is everything for himself, no one is anything for another. (…) They still have leisure time left over in which to invent and make all sorts of instruments, even watches (…). Though it seems unbelievable, each joins in himself the various crafts into which watchmaking is subdivided and makes all his tools himself. (…) These singular men are an astonishing combination of delicacy and simplicity that would be believed to be almost incompatible and that I have never since observed elsewhere.

-

- The Greubel Forsey workshops, between La Chaux-de-Fonds and Le Locle. As though sprouting from a (restored) farmhouse, mechanical watchmaking takes off…

The image of the farmer-watchmaker, their existence made all the more heroic by the bitter winters endured in their remote mountain homes, their self-sufficiency, their freedom – none of the rigid corporations that existed in Geneva or elsewhere – and independence, forged a “creation story” that would be widely repeated, reinforced by the carefully cultivated narrative of Daniel JeanRichard (1665-1741). Tales of this blacksmith’s son, credited as the founding father of watchmaking in the Swiss Jura, lent further credence to the notion of manual intelligence and independence. Here was proof that anyone could rise above their humble origins by the skill of their hands, adding to the image of an autonomous “aristocrat-worker” coming from peasant stock.

Still, a myth survives because it is rooted in truth. Life in these isolated altitudes was hard. Agriculture limited. But there was wood, iron, peat and wool in abundance, as well as long winters cut off from the rest of the world. The same farmers who made “countless artifacts with their hands”, and were skilled ironworkers, found an outlet for their talents in this new craft. Their wives worked alongside them tatting lace, an activity that was equally demanding in patience and precision.

Entirely by hand

Looking beyond the myth, watchmaking developed in these countries because their inhabitants were adept at working with their hands, as Rousseau noted. It also benefitted from a Protestant ethic, which encouraged discipline and work, from the necessary solidarity between places and families, and the pride these men took in their independence, organising their time as they saw fit.

-

- The watchmaker’s room, Musée Paysan et Artisanal, La Chaux-de-Fonds.

- Photo Guillaume Perret

Their surroundings were entirely of their own making. The farmer-watchmakers grew their own food, distilled their own alcohol, built the stone walls on their farms, sawed and assembled every table and chair, chopped the wood for the fires that warmed them, wove, stitched, ground and gathered. Nothing distinguished home from workplace, workplace from home.

-

- Views of the Musée Paysan et Artisanal

This environment is charmingly recreated at the Musée Paysan et Artisanal rural and craft museum, situated just outside La Chaux-de-Fonds in a farm that dates from 1612.

From window to factory

This idyllic model of the independent, self-sufficient farmer-watchmaker would soon be challenged as, economically and commercially, a new form of labour organisation emerged. Trade was spreading beyond Switzerland and into the world, even reaching China (the “Bovets of China” were among the Val-de-Travers watchmakers doing business with the East). Etablissage, a far more efficient and controllable system, became the dominant model. Individuals specialised in making one or other component, collected by the établisseurs who assembled them and distributed finished production.

-

- Workers leaving the Longines factory, before 1889, anonymous sketch

-

- Scene from Unrueh, directed by Mathias Schäublin (2023)

There was no longer time to till the land. The farmer-watchmaker became the “watchmaker at his window”, assisted by his entire family. Hamlets and villages focused on production of a given component. A pre-industrial fabric was taking shape, composed not of autonomous artisans but specialised workers. Families, sometimes a whole village, became suppliers dependent on the work provided by their établisseur.

-

- Fully automated production line, Miyota

A corner had been turned on the road to the Manufacture, a centralised structure where components were made then assembled into products which were sent to markets around the world. The age of the brand had arrived.

Brand not hand

Every object crafted by a farmer-watchmaker bore the mark of its maker’s hand. First mechanisation then industrialisation would anonymise production. The artisan’s hand disappeared. The brand had complete control of the product. Or rather products, all identical. Machines have no emotions. Their purpose is to reproduce the same thing, over and over.

This semi-industrial then industrial model enabled the extraordinary global success of Switzerland’s mechanical watch industry throughout most of the twentieth century. Brands sprang up in their hundreds… stopped in their tracks by the technological revolution that was quartz. The summit of industrialisation, quartz did away with the human hand entirely. Production was fully automated. Watches were soulless, mass-manufactured objects.

The myth returns

As a model died, a myth was born. Switzerland’s answer to this transformation of the watch from an object for life into an ephemeral fashion fad would come from below as well as above. From below with the Swatch watch (1983), which took quartz’s industrial logic as far as it could go by simplifying its construction to the extreme, and exploited every possibility as a fashion accessory. From above by reviving the myth of the farmer-watchmaker. An advertisement published by Blancpain (relaunched in 1982) in a 1985 issue of Europa Star makes explicit reference to the mountain origins of “the horological art” while declaring its “fidelity” to this tradition.

-

- Blancpain’s “manifesto” in a 1985 issue of Europa Star

In reality, a bond exists between “the last artisan watchmakers” (the title of a book which Roland Carrera, a respected watch journalist, published in 1976, amidst the throes of quartz) and a young generation of independents that has never been entirely broken.

Master watchmaker Michel Parmigiani experienced this connection first-hand. He was 14 in 1964 when he met Albert Bernet, the last surviving farmer-watchmaker.

Teachers at Parmigiani’s school in Fleurier had organised a competition for pupils to design a project which, if selected, would be shown at the forthcoming Swiss national exhibition. Along with a couple of classmates, Michel Parmigiani decided his subject would be the man everyone referred to as “old father Bernet”: the last farmer-watchmaker who lived alone in his farm, above the village of Travers. “The man who let us into his workshop, filled with rudimentary tools, was grumpy as a bear. He mumbled at us while puffing away on his pipe and did everything he could to dissuade us from entertaining any thoughts of becoming a watchmaker,” he recalls.

The three friends’ entry was turned down. Expo64 was about progress and the future. The main attractions included Jacques Piccard’s Mésoscaphe (the first passenger submarine that received the visit of Walt Disney in person), a monorail and Gulliver: a revolutionary computer that was meant to display the results of visitors’ answers to a survey on the major topics of the day. No-one cared about an old man making clocks on his farm.

-

- Marcel JeanRichard-dit-Bressel, photographed by Oberbesch in the early 1970s

“I clearly remember that day, although my interest in watchmaking came later,” Michel Parmigiani says, recalling his encounter with another “old-school” watchmaker: Marcel JeanRichard-dit-Bressel.

“I was interested in historical objects, fascinated by all these wonders but it seemed the science behind them had disappeared.” Meeting Marcel JeanRichard-dit-Bressel would prove decisive for the rest of Michel Parmigiani’s career. A direct descendant of Daniel JeanRichard, at more than 80 years old he still practiced his art in his tiny workshop in Les Brenets, not far from Le Locle.

Interviewed by Roland Carrera in the 1970s, Marcel JeanRichard-dit-Bressel spoke about being “one of the last in the region still making complicated pieces, minute repeaters, astronomical clocks, perpetual calendars, but that’s because all the others have died. I’m past 80 and recently finished an incomplete ébauche from old Breguet’s day. He started two but only finished one. It was owned by Mr Foster Dulles who lent it to me. It shows solar time and legal time, the date by a hand that makes one rotation in one year and has another small hand pointing to the day of the week. It was already fitted with a shock-absorber, built by Breguet.”

Learning from the past

After training in watchmaking at the Technicum in La Chaux-de-Fonds, followed by a diploma in micromechanical engineering in Le Locle, and having met the man who would pass on part of his precious expertise, in 1975 Michel Parmigiani opened what would become a successful business restoring antique timepieces, well before launching his brand in 1996.

Restoration – relearning what it is to work by hand – would be the way forward for the emerging cohort of young independent watchmakers who came together as the Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendants (AHCI), founded in 1985 by Svend Andersen and Vincent Calabrese. The AHCI would welcome the crème de la crème of independent watchmakers – the likes of Felix Baumgartner (future founder of Urwerk), George Daniels, trailblazer Philippe Dufour, Vianney Halter, François-Paul Journe, Bernhard Lederer, Antoine Preziuso and Kari Voutilainen, helping to forge this new and burgeoning artisanal haute horlogerie.

-

- Albert Bernet’s workshop, transferred to Musée des Mascarons, Môtiers.

Initially ignored — and relegated by management at the Basel fair to the very back of the furthest hall — the Académie’s members showed themselves to be endlessly innovative, both in the mechanisms and design of their watches. Such prowess didn’t escape brands’ notice for long and the AHCI would play a crucial role in mechanical watchmaking’s revival. As well as preserving traditional craftsmanship – hence the essential role of the hand –, these independents revived interest in the historic grand complications as much as they gave them contemporary visual appeal. They invented a bold, sometimes acrobatic style and, without realising, without even wanting to, paved the way for mechanical watchmaking’s elevation to luxury status.

-

- Julien Tixier’s workshop today, in Vallée de Joux.

Thanks to them (or because of them, one might be tempted to say), the tourbillon went from being a long neglected rarity to a rite of passage for any brand wishing to demonstrate its horological chops. From a few dozen a year in the 1980s, today’s estimates place annual production at between 15,000 and 20,000 tourbillons. Not all of which, not by a long chalk, rotate inside a hand-wrought cage.

The influence these modern-day “watchmakers at the window” have had on the industry as a whole is brilliantly demonstrated by the Harry Winston Opus concept watches, masterminded by Max Büsser (who continued his pioneering work with the creation of MB&F). A hybrid of luxury, innovation and hand-crafting, the series debuted in 2001 with François-Paul Journe, followed by Antoine Preziuso, Vianney Halter, Christophe Claret, Felix Baumgartner… all AHCI members. Later, the project drew from a wider pool, bringing in Greubel Forsey, Andreas Strehler, Frédéric Parinaud, designer Eric Giroud in tandem with watchmaker Jean-Marc Wiederrecht, Emmanuel Bouchet, and so on until the final Opus 14 in 2014 (the decision to end the series was made by Swatch Group, Harry Winston’s new owner).

The return of old father Bernet

The Opus adventure lasted 14 years. Fourteen years during which the face of Swiss watchmaking changed profoundly. Today we could ironize that every brand makes its own little Opus.

This first band of “neo-farmer-watchmakers” — most are still active though fortunes have varied: not all had a knack for business or the desire to take on the jungle of distribution — has given rise to a “new wave” of very young watchmakers, in Switzerland and around the globe, who have every intention of holding on to their independence. Often admirative of classical watchmaking, they aspire to master the finest traditional techniques without relinquishing their desire to innovate and explore new ground in complete freedom.

-

- Some of the new “watchmakers at the window”. From left to right and top to bottom: Alexandre Hazemann, Julien Tixier, Olivier Mory, Luc Monnet, Shona Taine, Sylvain Pinaud.

Like their now distant ancestors, they ply their craft in isolated workshops, often away from towns, in the Jura valleys or other remote locations. They know each other, collaborate and share their experiences.

Old father Bernet would spin in his grave were he to discover the fruit of their labours but he would also, begrudgingly no doubt, recognise that they are not so very different after all.