atchmakers began taking an interest in silicon, a metalloid found in abundance in the earth’s crust, of which it constitutes 28 per cent, at the end of the 20th century. Known since antiquity but isolated for the first time only in 1823, it was transformed into monocrystalline silicon by the French chemist Henri Sainte-Claire Deville in 1854. The base material for the manufacture of transistors, printed circuits and microchips, it revolutionised the computer industry and gave its name to Silicon Valley.

The keen interest of the watchmaking industry in this material is explained by its exceptional properties. It is elastic but non-deforming, which means that on receiving a shock it moves and immediately returns to its initial shape. It is extremely hard (1,100 Vickers compared with 700 Vickers for steel), light (with a density of 2.33g/cm3 compared with 8g/cm3 for steel), highly corrosion-resistant and – invaluable in watchmaking – insensitive to magnetism. But it also has its defects. It is as brittle as its cousin, glass, and sensitive to variations in temperature.

But research overcame this double handicap around the same time as wafer technology was developing, wafers being the thin slivers of silicon from which the tiny, high-precision parts needed in watchmaking can be cut out.

“A whole new dimension in mechanical watchmaking”

The first use of silicon in watchmaking was the work of Ludwig Oechslin for Ulysse Nardin with his revolutionary Freak, presented in 2001, the first movement to include silicon components. But this pioneering achievement, made as a demonstration, remained an exception for some time. Silicon’s first, grand entrance into “traditional” watchmaking came thanks to Patek Philippe, who took the world by storm in 2005 with a world premiere: an escape wheel in monocrystalline silicon for a Swiss lever escapement.

The announcement created a sensation and the triumphantly worded press release of the time describes “an innovation the importance of which cannot yet be measured, but which opens up a whole new dimension in mechanical watchmaking”.

Requiring no lubrication, more perfectly shaped and more accurate than a steel escape wheel, this silicon escape wheel served to equip a special, limited series of 100 pieces of the Annual Calendar Ref. 5250, the first series from the Patek Philippe Advanced Research unit. It was officially offered to “a limited circle of collectors and watch-lovers with a passion for technological exclusivities so they can be the first to take advantage of an innovation that will mark a turning point in the watchmaking industry”.

At the time, many observers shrugged their shoulders at the announcement. But what followed indeed showed that Patek Philippe was not exaggerating and that silicon was destined to become de rigueur across the watchmaking sector.

The consortium

Patek Philippe was not the only watchmaking entity to be working on silicon and its potential uses. Initially, the Geneva-based company had collaborated with the IMT, a microtechnology research centre at the University of Neuchâtel, in its research work. But to explore more deeply into the material’s watchmaking potential, a consortium made up of Patek Philippe, Rolex and the Swatch Group was created at the Swiss Centre for Electronics and Microtechnology (CSEM) in Neuchâtel.

The research undertaken by this consortium resulted in the industrial production of silicon balance springs. A strategic step forward.

The great fear at first was that despite all its qualities silicon would turn out to be too brittle and too sensitive to temperature variations to be used for balance springs. But the solution devised thanks to their joint research was oxidisation, which created a fine “bark”-like layer making it more rigid and protecting it from temperature variations. As a tribute to Charles Edouard Guillaume, winner of the Nobel Prize in 1920 for his invention of the famed Invar, which enabled the effects of temperature on a metallic balance spring to be minimised, this technology was named Silinvar®.

The great fear at first was that despite all its qualities silicon would turn out to be too brittle and too sensitive to temperature variations to be used for balance springs. The solution was oxidisation.

Gradual introduction

With this major technological advance as their starting point, the members of the consortium each developed their uses of silicon more or less rapidly. Capitalising on its momentum, Patek Philippe introduced its isochronous Spiromax® balance spring in 2006, its Pulsomax® escapement (escape wheel and lever) in 2008, complemented by the GyromaxSi® balance in gold and Silinvar® in 2011.

Together, these innovations, gradually released in limited editions by Patek Philippe Advanced Research, form a complete, high-tech regulating organ called Oscillomax®, which was inaugurated the same year in the extra-thin self-winding 240Q Si calibre (Q for Quantième Perpétuel, or Perpetual Calendar; Si for Silinvar®).

Here, silicon demonstrates the decisive advantages of its light weight, unusual geometry and excellent aerodynamics, which double the power reserve and allow the exceptional degree of accuracy of -3/+2 sec per 24h. Today, ten years later, silicon is present in 95 per cent of Patek Philippe watches. Consecration, one could say.

-

- The Patek Philippe 5650G Advanced Research Aquanaut Travel Time White Gold, produced in a limited series in 2016, combines multiple innovations. It features a high-tech silicon regulating organ alongside a second innovation: a reset mechanism in which the usual pivoting joints are replaced by “compliant” or flexible components. This mechanism, comprising just 12 openworked steel parts, featuring a number of springs with interleaved blades (compared with the 37 components of a traditional mechanism), transmits information from the two GMT pushers to the local time display.

Rolex waited until 2014 before introducing its balance spring, Syloxi, in the women’s calibre 2236 for the Oyster Perpetual Datejust Pearlmaster 34. Made in a composite of silicon and silicon oxide, it inaugurated a patented geometry that optimised its isochronism. After all, the brand with the crown logo could afford to wait: as regards the key topic of anti-magnetism, this innovation had its parallel in the Parachrom Bleu paramagnetic balance spring that the brand had launched back in 2000.

As for the Swatch Group, it went on to introduce silicon in 2009, first of all at Breguet, then at Omega, before gradually extending its use to nearly all its brands, including Tissot – with its Tissot Powermatic 80 – Certina and Hamilton. This industrial development was spearheaded by ETA and Nivarox – the latter, incidentally, being the company that supplies the great majority of Swiss watchmakers with traditional balance springs. The Swatch Group is successfully democratising silicon thanks to its industrial clout, while making a great leap forward at the same time.

Democratisation in progress

Initially, silicon balance springs were the preserve of the high-end brands because manufacturing them was costly: around CHF 100 a piece. Moreover, since the consortium members owned the patent, independently of one another they all did complementary research on manufacturing processes, geometries and different treatments, filing patents as they went, to be able to use this innovation in as many different ways as possible and at an industrial level. All this has had the effect of lowering the price of a silicon balance spring today to around CHF 20.

But the initial patent concerning the oxidation of silicon to make it insensitive to temperature variations is soon to enter the public domain – in November 2022 for Europe and in 2023 for Japan. Silicon technology, with its proven reliability, will therefore be available to all the players on the watchmaking stage.

The initial patent concerning the oxidation of silicon to make it insensitive to temperature variations is soon to enter the public domain – in November 2022 for Europe and in 2023 for Japan.

-

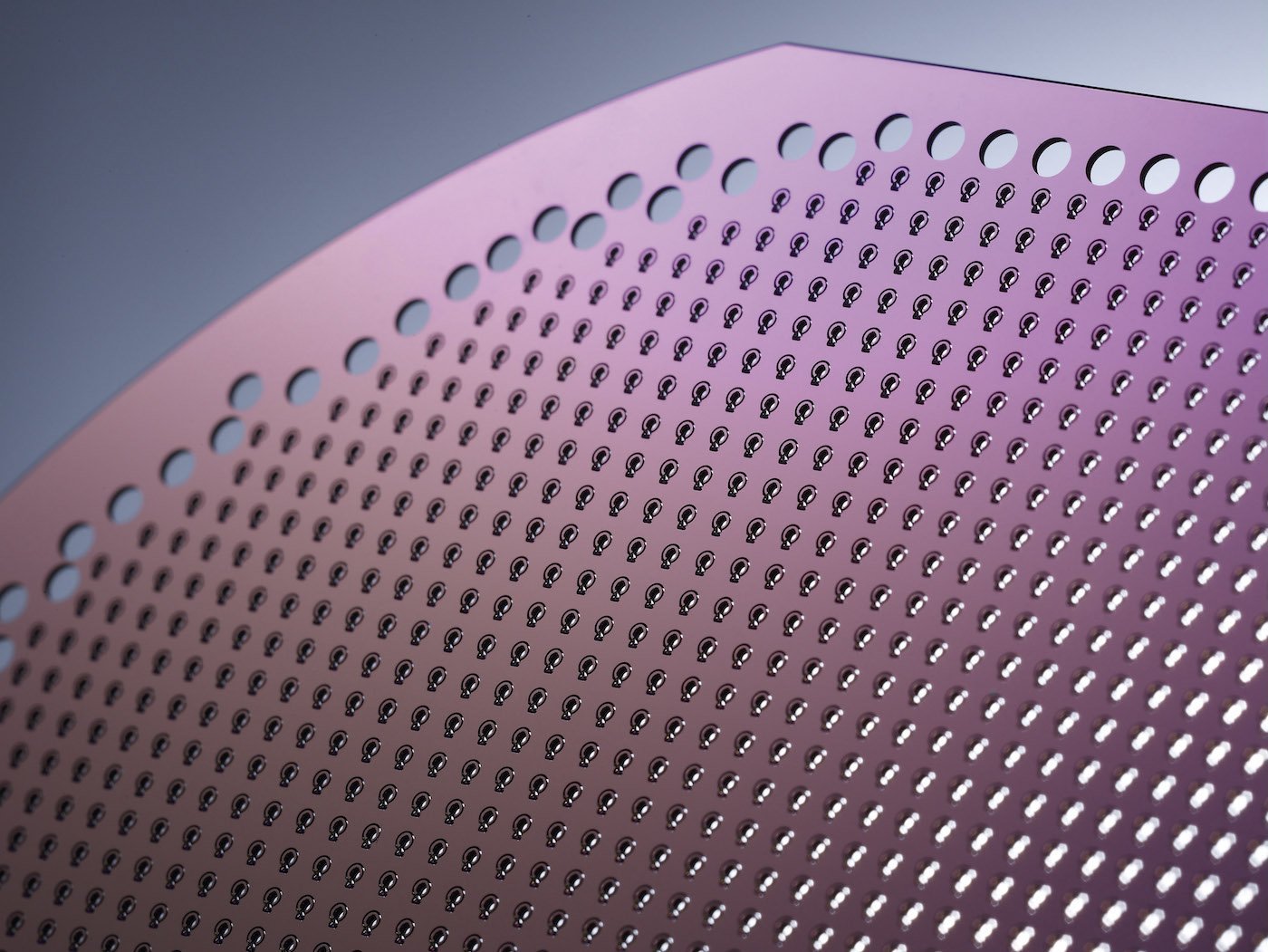

- A clean room where silicon components are produced (photo Patek Philippe)

Sigatec, a major player

And one major player in this technology, currently occupying centre stage, is Sigatec. This spin-off from Mimotec (bought by the Acrotec Group), founded in 2006 and owned equally by Mimotec and Ulysse Nardin, is a pioneering manufacturer of silicon micromechanical components. Now with a workforce of around forty, this ultra-high-tech company based in the canton of Valais, with its costly clean rooms, is active in the watchmaking industry but also in the biomedical sector, microfluidics and connector technology, churning out more than one million parts year.

For Marc-André Glassey, CEO since the company’s inception 15 years ago, the opening of the patent to the public domain represents a crucial development opportunity. “In 15 years, we’ve had time to acquire solid, detailed know-how that has enabled us to really build up this business,” Marc-André Glassey told Europa Star.

“The opening up of the patent to the public domain, which will free up the balance spring market, is certainly promising. What’s more, we’re expanding our premises by buying a factory next door to Mimotec, where we’ll be opening a new clean room, which means very substantial investment. But as always, there will be the early users and late adopters. While some brands are already making announcements, others are adopting a wait-and-see attitude. But they’ll all come, sooner or later.”

“As always, there will be the early users and late adopters. While some brands are already making announcements, others are adopting a wait-and-see attitude. But they’ll all come, sooner or later.”

Silicon, transforming the watchmaking industry

Marc-André Glassey also points to developments in demand that foreshadow transformations ahead in the Swiss watchmaking industry. “Manufacturers increasingly want ready-mounted oscillator subassemblies which, given the volumes required, is forcing us to automate assembly. Demand is clearly heading towards a finished, assembled product.” With the silicon oscillator, the actual assembly of the movement as a whole is considerably simpler. Instead of dozens of operations, a single operation suffices. A change that could transform watchmaking itself.

The democratisation of silicon is under way. Other patents will gradually enter the public domain – in 2023 that of the Patek Philippe outer terminal curve and its “bosses”, which reduce differences in rate, then in 2037 that of the inner curve.

Does this mean that this now highly effective technology is going to become ubiquitous in Swiss mechanical watchmaking? Marc-André Glassey reminds us that the number one after-sales service problem is related to damage from magnetism. “So anti-magnetism is a major issue, as demonstrated by Rolex, Tudor and Omega with their innovations. On that score, silicon is ideal. But in the future, the market is going to be divided solely between silicon balance springs and non-magnetic metal balance springs.”

The brands will be differentiated by which they opt for. We can already imagine a marketing battle over the key theme of resistance to magnetic fields – like the joint announcement by the Swatch Group and Audemars Piguet (in 2018) about the “revolutionary balance spring” carved out of a new, amagnetic compensating alloy called NivachronTM.

-

- Anchors on wafer

New escapements

But there is more to silicon than balance springs. This technology has also opened the door to a whole series of new approaches to watch regulation and escapements.

Without going into all these innovations in detail, let’s just mention the innovative escapements made possible by the use of silicon, such as the famous Zenith Defy Lab concocted by Guy Sémon and his teams, the Genequand Regulator presented by Vaucher Manufacture, which marries structures based on flexure bearings with silicon technology, the Constant Escapement from Girard-Perregaux, based on the instability of a buckled silicon blade, the numerous explorations and designs by Ulysse Nardin, or, even more recently, the monolithic silicon oscillator by Frederique Constant, beating at 40Hz.

Might these specific applications of silicon’s potential one day supplant the use of silicon in the strict conceptual framework of the traditional lever movement? While Marc-André Glassey professes “admiration for these systems”, to which he actively contributes with Sigatec, his view is that they will remain “specialities, niche products that are not going to replace the traditional, high-tech escapement ”.

There is more to silicon than balance springs. This technology has also opened the door to a whole series of new approaches to watch regulation and escapements.

“The fields of possibility are open”

Yes, but... innovation is a continuous process and whether silicon or some other material, “the fields of possibility are open”, says Philip Barat, who heads up R&D at Patek Philippe (a vertical, integrated applied research department employing 150, 50 of these alone involved in prototyping).

“Our research focuses in particular on flexibility. We have already explored and made metal flexure bearings. Lots of things are becoming possible today. Just take the example of the spring, which paradoxically weakens when put under tension! Other materials are also being explored, such as phosphorous, research is being done into thermal treatments, elasticity levels and so on. There’s much to be done in mechanics, new materials, powders, metallic glass. The future lies in new, ever finer, ever more efficient materials.”

Silicon has not yet said its last word by a long stretch. But now it is also having to compete with other materials that are emerging or under development. As for the escapement, there is every chance that silicon escape wheels will become the rule in the near future.

To set themselves apart, and backed by strong scientific, technical and economic arguments, the brands are going to put their money on high-performance alternatives. After decades of absolute supremacy of the traditional Swiss lever escapement with a metal balance spring, are we heading towards an atomisation of the modes of regulation in mechanical watches? Only the future will tell.

“There’s much to be done in mechanics, new materials, powders, metallic glass. The future lies in new, ever finer, ever more efficient materials.”

HORAGE IN THE STARTING BLOCKS

Andi Felsl, who heads up Horage (a small team that delivers a big punch, as the Biel-based brand styles itself), has already made the announcement: as soon as the patent for producing silicon balance springs insensitive to temperature fluctuations enters the public domain in autumn 2022, Horage will be ready to launch the Supersede model fitted with its own silicon balance spring.

Convinced that silicon is “the only way” forward, Andi Felsl sets out his roadmap. “We started by taking a close look at all the patents, all the options. Little by little, we learned and mastered the technology [editor’s note: with the help of the German institute Hahn-Schickard-Gesellschaft für angewandte Forschung e.V.]. But we couldn’t use it. Innovation was blocked for 20 years. Innovation is low when the market is high, as the saying goes. But today, we’re ready. Prices have sunk, but they were artificially high.”

The proprietary silicon regulator by Horage will be mounted on a movement developed and produced by the brand itself. For Andi Felsl, that represents “a huge economic advantage”.

“Silicon is more expensive,” he explains, “but ultimately you make major savings because the adjustment times for a traditional balance spring are lengthy and costly. And the ensuing tests, like the COSC for example, are expensive too. But to get to that stage, we had to learn to master the entire industrial process, especially assembly. The work flow was completely different. The industrialisation was the most difficult part, but now we control every stage. Horage’s goal is to offer high-performance products at affordable prices. Silicon will enable us to attain the performances we’re aiming for at acceptable prices we believe in [editor’s note: between CHF 2,300 and CHF 12,000].”

“Silicon provides better chronometry when produced at an industrial level,” he adds. “That’s where the future of Swiss watchmaking lies, in high-performance watchmaking. Because its volumes are not going to increase. They are going to flatten out at six million mechanical watches a year. But the product itself is going to improve more and more. Which will make it all the more attractive. We survived the quartz crisis. Silicon is our ally in the next stage of the adventure.”

“Silicon is more expensive, but ultimately you make major savings because the adjustment times for a traditional balance spring are lengthy and costly. And the ensuing tests, like the COSC for example, are expensive too.”